There is an old saying in American politics: If you don’t like the politicians you’ve put in office, you can always “throw the bums out.”

But that’s not how things often play out in the real world of politics in America. Americans disdain Congress as an institution, but, like clockwork, they keep re-electing the same people every two years.

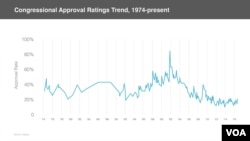

Consider Congress’s dreary approval ratings ahead of the November 8 elections. According to a Gallup survey conducted October 5-9, only 18 percent of Americans approve of the job Congress is doing. That's comparable to Congress's pre-election approval ratings in the last four election cycles.

The findings come as the vast majority of congressmen running for re-election – whether Democrats or Republicans – are expected to sail to victory by double-digit margins.

According to the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, just 25 out of 435 House seats are considered “toss-ups” – or truly contested -- while only seven of 34 Senate races are considered in that category.

That suggests that more than 90 percent of House members and 80 percent of senators running for re-election are certain to return to office.

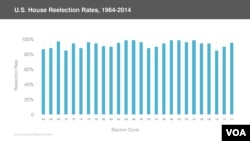

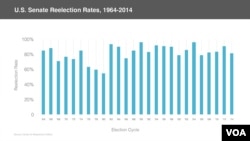

The forecasts are broadly in line with historic trends. In the past 50 years, more than 90 percent of House members and more than 80 percent of senators have won re-election, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics, a Washington-based bipartisan watchdog.

Re-election rates

In 2014, the re-election rate for House members was 95 percent, with those members winning by an average margin of victory of 36 percent. In the Senate, 82 percent of the lawmakers were re-elected, with incumbents winning with an average margin of victory of 23 percent.

So what explains the apparent paradox of the unpopularity of Congress and the high rates at which incumbents are re-elected?

One explanation is that while Americans distrust Congress as an institution, they like their own representatives.

That is partly a reflection of a deeply polarized electorate that blames the other party for Congress' perceived faults and partly a result of tools used by incumbents – from touting their work on behalf of their districts in newsletters to constituents to walking in holiday parades -- all of which tend to cast them in a favorable light.

“They can talk about how horrible things are, how the other party is blocking them,” says Viveca Novak of the Center for Responsive Politics.

Redrawing of districts

Another reason the lawmakers have a long shelf life is “gerrymandering,” the partisan practice of manipulating congressional districts for political gain after each national Census every 10 years.

In most American states, the redistricting process is controlled by state legislators who pack their opponents’ supporters into as few districts as possible while spreading their own loyalists across a larger number of districts.

Because of gerrymandering, the last round of which followed the 2010 Census, a majority of congressional districts are now controlled by one party or the other, making entry into a race by challengers practically impossible.

“Unfortunately, in the United States there are very few swing districts in the U.S. House of Representatives,” said Dan Vicuna, a redistricting expert at Common Cause, a political advocacy organization. “And that makes it more difficult for challengers to gain access to funds, to really put up a fight, to make an election competitive.”

A Common Cause study released at the end of October ((October 26)) found that because of gerrymandering, about 33 million people in 47 districts will see only one major-party congressional candidate on the ballot on November 8.

“Voters are being denied choices, a real choice between two major-party candidates when self-interested legislators draw districts,” Vacuna said. In many districts, “the campaign was over” even before the primary election.

There is also what Christopher Deering of George Washington University calls “natural gerrymandering,” the tendency by some American voters to relocate to districts already populated by like-minded partisans, as in Republicans moving to GOP-leaning rural areas.

The “malapportionment of voters” through gerrymandering makes “a district particularly difficult to win whether you’re a high-quality, high-name recognition candidate or not," says Deering, a political science professor who is an expert on American political institutions.

Power of incumbency

“To some degree, these are hard to separate,” Deering said.

Members of Congress are more likely to appear on television news than their lesser-known challengers to be invited to "policy- or party-neutral" events, he added.

Money is key to winning increasingly expensive elections and incumbents have a distinct fundraising advantage over challengers. Though they do sometimes bet on open races with promising candidates, special interest groups and other donors are far more likely to give money to incumbents than to challengers.

That is because special interest groups favor predictability and incumbents represent certainly, Novak explained. With challengers, "you don’t know what you’re going to get,” he added.

With no limits on campaign spending, the financial advantage allows incumbents to far outspend challengers during re-election campaigns, often by a margin of at least 3-to-1.

In the 2014 elections, for example, the average incumbent senator facing a challenger spent nearly $12.5 million compared with more than $4.5 million spent by an opponent. In the House, the average incumbent outspent a challenger nearly $1.5 million to about $350,000, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Calls for reform

The institutionalized barriers to competitive elections have led to calls over the years for electoral and campaign finance reforms.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a push for term limits – mostly by Republicans -- but the effort was abandoned when Republicans regained control of Congress and both parties opposed the idea, Deering said.

In more recent years, attention has turned to campaign finance reform and other efforts such as establishing shorter, less expensive campaigns and allowing independent citizen commissions to redraw electoral districts. But few of these efforts have gotten much traction.