A loosely-coordinated group of Syrian rebel factions earmarked by U.S. officials as a proxy army to partner with in northern Syria lacks coherence and reliability, warn analysts and rival rebel commanders.

Renamed the Syrian Arab Coalition last week by U.S. military commanders, the group would serve as an alternative to a ground force the Obama administration had hoped to recruit from scratch, train and equip.

The loose coalition of Sunni Arab factions, who have been collaborating with Syrian Kurdish fighters along the border with Turkey, may be provided with arms in a U.S. plan that would have them support re-equipped Kurds in a major offensive on Raqqa, the de facto capital of the Islamic State terror group.

According to U.S. officials, President Barack Obama gave the go-ahead at a meeting of the National Security Council last Thursday for the Pentagon to start directly rearming Syrian Kurds and the “Arab-Syrian opposition” as part of a strategy to put pressure on the Islamic State and to isolate Raqqa. At the same time the U.S.-led coalition would intensify strikes on the terror group with increased sorties launched from the NATO base at Incirlik in southern Turkey.

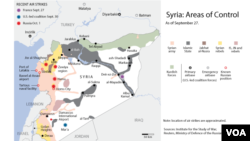

The move comes as Russia appeared to be on the brink of ratcheting up its intervention in Syria, adding a ground element to an aerial bombing campaign started last week — one that has shaken up an already complex battlefield and prompted comparisons to the proxy wars of the Cold War era.

Russian intervention

President Vladimir Putin’s military liaison officer to the Russian parliament disclosed Monday a plan to send “volunteer” troops to Syria to help buttress Moscow’s ally President Bashar al-Assad. The Kremlin claims its main target is the same as Washington’s — namely, the Islamic State. That claim is questioned by Washington because most Russian airstrikes have targeted anti-Assad rebels in western and central Syria as opposed to IS strongholds in the east.

U.S. officials insist they started to consider the re-supply plan for the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, and their Sunni Arab allies before Russia launched its air campaign. And last month Gen. Lloyd Austin, commander of American forces in the Middle East, appeared to outline a changed U.S. strategy when he told a congressional panel that the Obama administration planned soon to put “a lot more pressure on key areas in Syria, like the city of Raqqa.”

His comments were in the wake of the apparent acceptance by the Obama administration that an 18-month program known as train-and-equip to raise an indigenous Syrian Arab rebel proxy force to work with the U.S. to defeat IS had failed.

But the perception here among Syrian rebel commanders is that Russia’s airstrikes have added urgency to Washington’s plan to have the Kurds and Sunni Arab proxies mount a major offensive against IS— a bid they suspect is meant to change dynamics on the ground quickly before the Russian intervention gets into stride and to try to stop Moscow from appearing to seize the initiative.

Syrian Arab coalition

Commanders with both the Western and Gulf-backed Free Syrian Army and Islamist militias in the Army of Conquest alliance, who have been spurned by Washington because of their links with al-Qaida affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, are critical of the likely beneficiaries of the planned U.S. arms supplies — the so-called Syrian Arab Coalition, whose factions they dub “opportunists.”

They say the factions have a checkered history, one that has involved shifting allegiances and readiness at times to work with al-Nusra and the Islamic State.

One of the major factions — Liwa Thuwwar al-Raqqa — collaborated with Jabhat al-Nusra in Raqqa before the town was captured by IS. It broke with the al-Qaida affiliate last year and joined a loose confederation known as the Euphrates Volcano, the basic forerunner of the Syrian Arab Coalition.

Another faction in the new coalition, Jaysh al-Qasas, worked with IS in 2014. FSA commanders say its leader spends most of his time in Turkey and his fighters are most interested in looting.

“They are fighters who have moved from one militia to another,” says Abdul Rahman, a commander with the Army of Mujahideen , which is aligned with Jaish al Fata, or the Army of Conquest, the Islamist rebel alliance.“Most of them are rejects. They are not reliable — we don’t trust them,” he told VOA.

Adding to the widespread distrust among the main rebel brigades is an overall suspicion of the YPG itself, which has as its over-arching objective to establish an autonomous Kurdish State in northeast Syria. They call the Sunni Arab factions working with the YPG, “Kurdish parties.”

FSA vs YPG

FSA and Islamist commanders have warned the YPG to stay in Kurdish areas and not to push into Arab villages. Earlier this year, they accused the YPG of displacing Arab families in villages captured by the Kurds. Mutual suspicion between the FSA and Islamist rebel militias, and the Kurds has deepened as Kurdish-led forces have gone beyond their traditional home territory.

In June, some of the armed groups at the heart of the Syrian Arab Coalition helped the YPG pull off a major and surprisingly easy victory, retaking the Syrian border town Tal Abayad from Islamic State extremists. But their contribution was marred when some of the Sunni Arab factions squabbled over who should govern the town after the jihadists left, prompting Kurdish exasperation, say town residents.

“The Kurds let them haul up the Syrian rebel flag but they [the Arab militias] then started bickering about who would control the town,” says Mohammed, a border smuggler who has worked with a variety of rebel groups. “In the end, the Kurds stopped the argument by saying they did.”

“I generally agree with the testimony of those rebels you have spoken to,” says Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, a fellow at U.S.-based think tank the Middle East Forum. He says that armed groups in one of the largest of the factions, the Dawn of Freedom, have “reputations for corruption.”

“The main groups of the coalition are splinters from larger rebel militias and in the case of Dawn of Freedom it is essentially a regrouping of militias that had reputations for criminality in North Aleppo, such as Ghuraba al-Sham,” he told VOA. Some of the factions were thrown out of an Islamist rebel alliance.

Al-Tamimi added: “The other components of the rebel allies with the YPG are small groups of locals who fled their homes in Deir ez-Zor and Jarabulus” after the Islamic State overran the towns. Some are members of the Shammar tribe in eastern Syria, which has suffered repeated IS reprisals and massacres.

Al-Tamimi says the Syrian Arab Coalition factions “have their own agendas that ultimately conflict with the YPG's but they don't have the power to challenge the YPG political wing's governing authority over places like Tal Abyad. They simply don't compare with the YPG in terms of strength.” He and other analysts estimates the Syrian Arab Coalition’s numbers from 3,000 to 5,000 fighters; the YPG can field about 25,000.

But al-Tamimi cautions that overall numbers are hard to assess with any firm reliability. During the months-long battle to keep the Kurdish border town of Kobani from falling into IS hands, the estimates of Sunni Arab fighters cooperating in the town with the YPG varied considerably. One of Dawn of Freedom’s leaders, Abu al-Layth, claimed 250 of his men went to Kobani but “the numbers steadily went down over time, from 160 fighters in a subsequent conversation down to 70.”

Kurdish political activists say the numbers and military capabilities belie the potential of the Syrian Arab Coalition. Kovan Direj, who has worked with the YPG in northern Syria, said the Kurds have been careful to avoid subsuming the Sunni Arabs cooperating with them. The YPG “armed the Arabs to defend themselves,” he says. And the Coalition could be the vehicle for several Arab tribes — not just the Shammar — to avenge IS killings. “They only need weapons to start,” he added.