Two-million-year-old fossils including the three tiny bones of the middle ear are helping scientists figure out the auditory abilities of early human ancestors at a time when they were beginning to hear more like a person and less like a chimpanzee.

A study published Friday involving two species from South Africa, Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus, showed they boasted better hearing than either chimps or people in a frequency range that may have facilitated vocal communication in a savanna habitat.

Both species featured a mixture of apelike and humanlike anatomical traits and inhabited grassland ecosystems with widely spaced trees and shrubs, as opposed to the forests of earlier members of human lineage.

In both species, maximum hearing sensitivity was shifted toward slightly higher frequencies compared to chimpanzees, and both had better hearing than chimps or humans in the range from about 1.0-3.0 kilohertz, paleoanthropologist Rolf Quam of Binghamton University in New York said.

Sounds in that range include vowels and some consonants, Quam said.

"It turns out that this auditory pattern may have been particularly favorable for living on the savanna. In more open environments, sound waves don't travel as far as in the rainforest canopy, so short-range communication is favored on the savanna," Quam said.

The human lineage split from chimps roughly 5 to 7 million years ago, Quam said, and our ancestors' hearing abilities began to adapt to lifestyle changes.

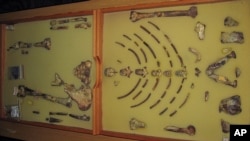

Middle-ear bones

To assess the two species' hearing abilities, the researchers studied fossils including tiny middle-ear bones called the ossicles (the malleus, incus and stapes) and created virtual computer reconstructions of the ear's internal anatomy.

Our species, Homo sapiens, which arose about 200,000 years ago, is distinct from most other primates in having better hearing across a wider range of frequencies, generally from 1.0 to 6.0 kilohertz. This range encompasses many sounds emitted during spoken language.

"I want to be clear that we are not arguing that these early humans had language, which implies a symbolic content," Quam said. "Certainly they could communicate vocally. All primates do. But human language emerged during our evolutionary history at some time after the existence of these early humans."

Paleontologist Juan Luis Arsuaga of Spain's Universidad Complutense de Madrid said their hearing abilities indicate their voices "would sound strange, half chimplike, half human, to us. Or in other terms, not completely human."

The research appears in the journal Science Advances.