STOCKHOLM —

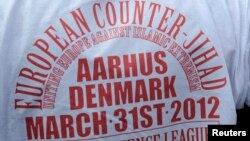

From spats over halal meat in Danish schools to asylum seekers in Sweden, anger about immigration has fuelled the march of populist parties across Nordic countries, leading one such group to the brink of government in prosperous Norway.

The anti-tax and anti-immigration Progress Party, which once had among its members mass killer Anders Behring Breivik, won 16 percent of votes on Monday and could be kingmaker in a new center-right coalition after eight years of center-left rule.

Its strength reflects both worries about an influx into the Nordics of asylum seekers from countries like Syria and economic migrants from Spain, as well as disenchantment with mainstream parties that have dominated the political landscape for decades.

“We'll ensure a solid footprint in a new government,” Progress leader Siv Jensen said. “We have reason to celebrate.”

Even without entering government, right-wing populists have managed to toughen public policies ranging from immigration to euro zone bailouts, drag political debate to the right and become a permanent feature of the parliamentary landscape.

The backlash has surfaced even though Nordic economies have outperformed languishing southern European countries. Their success has attracted thousands of “euro refugees”, vying for scarce jobs as their home states endure grinding austerity.

Economic conditions may be different, but many voters around Europe share the same perception that the established parties are out of touch with ordinary people and their concerns.

From Greece to France and the Netherlands, unemployment and economic grievances have combined with suspicion of European integration, Islam and multiculturalism, to propel both the far right and far left.

In Italy, the grassroots 5-Star Movement, born of disgust at the entire political establishment, surged to prominence in a general election in February. Britain's UK Independence Party has gained ground and spooked mainstream politicians by harnessing an anti-EU platform with hostility to immigration.

Back from the sidelines

Breivik's killing of 77 people in Norway in 2011 initially set back hard right parties in the Nordics.

But the Danish People's Party now has the support of nearly one in six voters. The anti-immigrant Sweden Democrats have almost doubled their support since the last general election to touch 10 percent, and Finland's opposition Finns party stands second in opinion polls with 19 percent support.

Populist groups are nowhere near winning an election and the majority of Nordic voters still express tolerance to immigrants. But any of these parties could secure the balance of power and hold a coalition government hostage on issues like immigration.

Consensus around the post-war Nordic model of high taxes and generous welfare was long sustained by a homogenous society. But immigration, global competition and fear for jobs have put that ideal of equality based on civic trust under strain.

“There exist groups that don't feel this trust,” said Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt. “These people as voters are more easily seduced by populist forces seeking short-sighted answers and which often are more or less hostile to immigrants.”

Rising immigration has been coupled with economic troubles that have seen iconic Nordic companies such as Ericsson and Nokia shed jobs. Worries about the affordability of welfare have put the once taboo subject of immigration high on the agenda.

The nightmare for mainstream Nordic parties would be the experience of Denmark's last government, when an anti-immigrant party held the balance of power and pushed for tighter border controls that fuelled tension with European neighbors.

Under Denmark's current center-left government, immigration had faded as an issue until controversy surfaced when it was discovered that halal meat, slaughtered under Muslim dietary laws, was being served routinely at schools and hospitals - raising protests by anti-Islam groups.

Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt waded into the debate - earning the nickname “meatball Helle' after calling for voluntary labeling of halal meat but also urging that traditional Danish food including pork dishes be served.

The construction of a mosque in Copenhagen sparked accusations from the Danish People's Party that it was being used for radical Islamist groups.

In Sweden, immigration has become part of the mainstream debate in a country where 15 percent of people are foreign-born, the highest rate in the Nordics. Riots in poor immigrant suburbs of Stockholm in May led to further debate about how Sweden was integrating its immigrants.

“Immigration is questioned by pretty considerable portions of the populace,” said Folke Johansson, a professor of political science at Sweden's Gothenburg University. “It's largely been taboo to discuss these issues, and therefore other mainstream parties haven't been able to discuss it. It was really an open goal once they (anti-immigration parties) arrived on the scene.”

In Finland, the Finns party, whose anti-euro rhetoric struck a chord with voters in 2011, when they finished a close third in parliamentary elections, aims to join the next government.

Formerly known as True Finns, The Finns leapt to prominence during the euro zone debt crisis by opposing bailouts for troubled countries. They effectively forced the government to demand collateral in exchange for helping Greece and Spain.

Calling themselves a “nationalistic and center-left working class party,” the Finns would curb immigration by trimming immigrant social benefits and adjusting refugee quotas to Finland's financial situation.

These parties have benefited from media-savvy leaders. The Sweden Democrats' Jimmie Akesson, whose aim is to reduce immigration by 90 percent, wears a suit and as a lawmaker has changed the party's former image of street ruffians.

Populists are expected to poll strongly in many countries in European Parliament elections next May, surfing a wave of Euroscepticism due to the financial and economic crisis.

But analysts say these Nordic parties may have hit a ceiling in national elections and are facing greater pushback even as they complicate coalition politics around the region.

Hundreds of Swedish women posted photographs of themselves with headscarves across social media this year to protest an attack on a Muslim woman in Stockholm who was wearing a veil.

Community leaders worry about aggressive rhetoric against migrants, and there have been other attacks. But violent incidents in Nordic countries have been isolated compared with, for example, far right attacks on migrants in Greece.

Reinfeldt's government recently made headlines by giving Syrians an automatic right of residence.

Support for Norway's Progress is actually down from 22 percent at the last election four years ago, although the parliamentary arithmetic gives it more leverage.

“The way Progress communicates is somewhat old fashioned and a bit cheesy,” said Daniel Gaim, 37, a teacher. “But when it comes to real policy, they don't differ much from other parties. I'm not very concerned about giving them a bigger influence.”

The anti-tax and anti-immigration Progress Party, which once had among its members mass killer Anders Behring Breivik, won 16 percent of votes on Monday and could be kingmaker in a new center-right coalition after eight years of center-left rule.

Its strength reflects both worries about an influx into the Nordics of asylum seekers from countries like Syria and economic migrants from Spain, as well as disenchantment with mainstream parties that have dominated the political landscape for decades.

“We'll ensure a solid footprint in a new government,” Progress leader Siv Jensen said. “We have reason to celebrate.”

Even without entering government, right-wing populists have managed to toughen public policies ranging from immigration to euro zone bailouts, drag political debate to the right and become a permanent feature of the parliamentary landscape.

The backlash has surfaced even though Nordic economies have outperformed languishing southern European countries. Their success has attracted thousands of “euro refugees”, vying for scarce jobs as their home states endure grinding austerity.

Economic conditions may be different, but many voters around Europe share the same perception that the established parties are out of touch with ordinary people and their concerns.

From Greece to France and the Netherlands, unemployment and economic grievances have combined with suspicion of European integration, Islam and multiculturalism, to propel both the far right and far left.

In Italy, the grassroots 5-Star Movement, born of disgust at the entire political establishment, surged to prominence in a general election in February. Britain's UK Independence Party has gained ground and spooked mainstream politicians by harnessing an anti-EU platform with hostility to immigration.

Back from the sidelines

Breivik's killing of 77 people in Norway in 2011 initially set back hard right parties in the Nordics.

But the Danish People's Party now has the support of nearly one in six voters. The anti-immigrant Sweden Democrats have almost doubled their support since the last general election to touch 10 percent, and Finland's opposition Finns party stands second in opinion polls with 19 percent support.

Populist groups are nowhere near winning an election and the majority of Nordic voters still express tolerance to immigrants. But any of these parties could secure the balance of power and hold a coalition government hostage on issues like immigration.

Consensus around the post-war Nordic model of high taxes and generous welfare was long sustained by a homogenous society. But immigration, global competition and fear for jobs have put that ideal of equality based on civic trust under strain.

“There exist groups that don't feel this trust,” said Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt. “These people as voters are more easily seduced by populist forces seeking short-sighted answers and which often are more or less hostile to immigrants.”

Rising immigration has been coupled with economic troubles that have seen iconic Nordic companies such as Ericsson and Nokia shed jobs. Worries about the affordability of welfare have put the once taboo subject of immigration high on the agenda.

The nightmare for mainstream Nordic parties would be the experience of Denmark's last government, when an anti-immigrant party held the balance of power and pushed for tighter border controls that fuelled tension with European neighbors.

Under Denmark's current center-left government, immigration had faded as an issue until controversy surfaced when it was discovered that halal meat, slaughtered under Muslim dietary laws, was being served routinely at schools and hospitals - raising protests by anti-Islam groups.

Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt waded into the debate - earning the nickname “meatball Helle' after calling for voluntary labeling of halal meat but also urging that traditional Danish food including pork dishes be served.

The construction of a mosque in Copenhagen sparked accusations from the Danish People's Party that it was being used for radical Islamist groups.

In Sweden, immigration has become part of the mainstream debate in a country where 15 percent of people are foreign-born, the highest rate in the Nordics. Riots in poor immigrant suburbs of Stockholm in May led to further debate about how Sweden was integrating its immigrants.

“Immigration is questioned by pretty considerable portions of the populace,” said Folke Johansson, a professor of political science at Sweden's Gothenburg University. “It's largely been taboo to discuss these issues, and therefore other mainstream parties haven't been able to discuss it. It was really an open goal once they (anti-immigration parties) arrived on the scene.”

In Finland, the Finns party, whose anti-euro rhetoric struck a chord with voters in 2011, when they finished a close third in parliamentary elections, aims to join the next government.

Formerly known as True Finns, The Finns leapt to prominence during the euro zone debt crisis by opposing bailouts for troubled countries. They effectively forced the government to demand collateral in exchange for helping Greece and Spain.

Calling themselves a “nationalistic and center-left working class party,” the Finns would curb immigration by trimming immigrant social benefits and adjusting refugee quotas to Finland's financial situation.

These parties have benefited from media-savvy leaders. The Sweden Democrats' Jimmie Akesson, whose aim is to reduce immigration by 90 percent, wears a suit and as a lawmaker has changed the party's former image of street ruffians.

Populists are expected to poll strongly in many countries in European Parliament elections next May, surfing a wave of Euroscepticism due to the financial and economic crisis.

But analysts say these Nordic parties may have hit a ceiling in national elections and are facing greater pushback even as they complicate coalition politics around the region.

Hundreds of Swedish women posted photographs of themselves with headscarves across social media this year to protest an attack on a Muslim woman in Stockholm who was wearing a veil.

Community leaders worry about aggressive rhetoric against migrants, and there have been other attacks. But violent incidents in Nordic countries have been isolated compared with, for example, far right attacks on migrants in Greece.

Reinfeldt's government recently made headlines by giving Syrians an automatic right of residence.

Support for Norway's Progress is actually down from 22 percent at the last election four years ago, although the parliamentary arithmetic gives it more leverage.

“The way Progress communicates is somewhat old fashioned and a bit cheesy,” said Daniel Gaim, 37, a teacher. “But when it comes to real policy, they don't differ much from other parties. I'm not very concerned about giving them a bigger influence.”