This is Part 4 of a 5-part series: Honoring Africa’s Traditional Music

Continue to Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

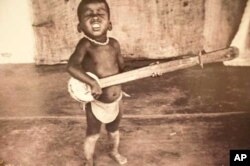

The photograph is blurry, perhaps to be expected from an image taken with a simple camera in 1946. In it, a little boy stands firmly on a concrete floor. He is naked - save for a cloth tied around his waist, shell beads around his neck and chalky dust that cakes his lower legs and feet.

The boy is strumming a guitar, made roughly from a wooden plank, wire and animal skin, in the room in which he lives on a diamond mining compound in the then Belgian Congo. His head is cast slightly backwards, his eyes tightly shut; his mouth open to reveal a perfect set of teeth, almost fluorescent in their whiteness.

It’s a powerful picture of the ability of music to offer transcendence, however momentary, to human beings eager to escape their often mundane and painful lives.

The photograph was taken by Hugh Tracey, a pioneer ethnomusicologist who spent half a century journeying through Africa, from the 1920s until his death in 1977, recording and preserving the continent’s indigenous music. It forms part of the ‘For Future Generations’ exhibition, currently in South Africa, to honor his legacy and to celebrate indigenous and ancient African music.

‘Most remarkable demonstration’

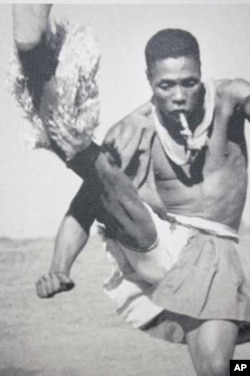

Upon entering the show, one is confronted by a black and white film projected onto a large wall. It was taken by Hugh Tracey in 1938 and shows Zulu men playing mouth bows with gourds attached as resonators.

There are photographs on the walls of Tracey recording musicians from myriad African ethnic groups. Glass cases are filled with ancient African musical instruments, such as likembe thumb pianos from the lower Congo River, wooden muranzi side-blown flutes from Zimbabwe and bamboo reed-pipes from Tanzania.

Six listening stations, replete with headphones, offer visitors the opportunity to hear a few of the more than 20,000 sound items collected by Tracey on his excursions across Africa. “It’s the most remarkable demonstration of Africa’s musical past,” said Prof. Diane Thram, the director of the International Library of African Music in South Africa.

First musicians were African

But, said Andrew Tracey, Hugh Tracey’s son and also an ethnomusicologist, based in South Africa, many Africans were “fixated” on the present and “don’t see the need” to respect the music of their forebears.

“Music for modern Africans means, basically, the music of where they are – which is mostly in cities and towns. People living in town want to make town music and that means very much Westernized music,” he said.

While Andrew understood this, and also understood why most modern Africans were “infatuated” with American rap, soul and R&B music, he was “at a loss” to explain why they weren’t “at least” trying to honor their musical heritage and the continent’s musical heroes of the past.

“Maybe they feel their roots music and instruments are inferior to those of the West. They shouldn’t feel this way, because they’re in many ways superior,” he commented, explaining further, “Anthropological finds prove that Africans were making music many, many centuries before anyone else. They were the world’s first musicians. Why Africans ignore this heritage is for someone more qualified than me to answer.”

Zulu folk masters

Andrew said another reason for indigenous African music not appealing to modern people, including Africans, was that “it makes a lot of demands on listeners. You can’t just listen to a traditional piece of African music and say, ‘wow, that’s great, groovy music.’ You have to listen to it (closely) and get into it and understand its meaning, its structure.”

He explained that many old African songs were structured like stories, not like modern songs, which generally have a chorus and a few verses and are “much easier to digest.”

He maintained, though, that Africa’s musical past was not just about complex story songs, but was also “overflowing” with “wonderful, melodious” compositions. “If people just dug a little deeper and became more open-minded, they’d find music like that made by the Herman Magwaza Guitar Band in 1950s South Africa,” said Andrew.

Magwaza and his group pioneered Zulu folk music. “This band proved that Zulu music is about far more than near-naked warriors banging on tribal drums. But who would know the beauty of the compositions made by Herman Magwaza if it wasn’t preserved, and if they didn’t bother to search out their past?” he asked.

‘The sound is in their blood’

Christian Carver manages a company that makes traditional African musical instruments in South Africa. Most of his sales, he said, were outside of Africa.

“African music has become disregarded even in Africa. I have so many (school) kids (visiting) here and you ask them, ‘can anyone tell me what this (instrument) is?’ And it’s from their own culture…. but they can’t,” Carver said, shaking his head. He continued, “Yet as soon as you play it, you see the lights go on in their eyes. And that’s because they have very, very strong cultural linkages to these instruments. The sound of these instruments is in their blood – but they don’t know it.”

As an example, he cited the uhadi musical bow, traditionally used by South Africa’s Xhosa people. “The musical scale that comes out of the (uhadi’s) overtone tuning system is the basis of Xhosa (musical) scales and so (Xhosa) kids recognize that instantly…. This happens even though in many cases they’ve never seen or heard an uhadi.”

African music = basis for modern pop music

Like Andrew Tracey, Carver believed the roots of modern music were in Africa. He stated, “It’s the African-ness (sic) of (modern) popular music that makes it popular. I believe that African music is the basis for all popular music.”

He cited a band such as the United States’ Vampire Weekend as evidence of this. Vampire Weekend mix African-influenced rhythms with modern chamber pop music, according to international music critics.

Andrew said perhaps the “greatest influence” on modern pop music was the music made in the past by black Americans. He asked, “And who were the forebears of these black American musicians? They were slaves from Africa, who took their music and rhythms and harmonies with them on the slave ships to America.”

Thram said, “So many young people are so ignorant about how African music has penetrated and effected and created all these new styles, like blues, that are based on African music.”

‘No more excuses’

Carver said while the “rest of the world” seemed to “tip their hat” to the immense influence of African music, “and even in monetary terms recognizes its value and the importance of preserving it,” Africans themselves, and especially the continent’s authorities, generally did not.

“Africans are disregarding it in favor of trying to sing Verdi and Bach and whatever. In (African) choir competitions, you might have one traditional number but everything else is tending towards the sort of western art music line,” said Carver.

This, Andrew maintained, wasn’t because African music of the past was inferior. “It’s just that Africans have for too long ignored their musical past. This of course is in large part to do with the terrible effects of colonialism, which taught that all things African were inferior, but we now know that this is nonsense. It’s time for Africa to stand up and reclaim its terrific musical past.”

But Andrew acknowledged that the achievement of this needed “significant” funding and the support of the continent’s political authorities. “As yet, there’s no sign of this happening,” he said.