Burkina Faso’s reelected President Roch Kabore has appointed a minister for national reconciliation as part of a vow to end the country’s ethnic and political conflicts that are fueling terrorism. However, resolving deep-rooted tensions over land and power between the ruling ethnic Mossi and the ethnic Fulani, who are often labeled as terrorists, will not be easy.

The Fulani are semi-nomadic herders living across Africa’s Sahel region — including Burkina Faso’s north, where Islamist terrorists gained a foothold in the last decade.

Daouda Dialo heads the Burkinabe rights group Collective Against Impunity and the Stigmatization of Communities. He says the country is in a situation today where some people think they are more Burkinabe than others. Dialo adds they go about killing their neighbors with impunity.

The U.S. State Department last year issued a report implicating the government in abuses, including extrajudicial killings and violence against ethnic minorities.

Due to recruiting among the disgruntled, rights groups say the Fulani are often labeled as terrorists and subject to abuse or even execution.

In September, three Fulani teenagers say a government trained militia targeted them while they were on their way to school.

One 16-year-old, who for security reasons does not wish to use his name, says the armed men stopped their school bus.

He says only Fulanis were told to get off the bus. They were whipped with a motorcycle brake cable, he says, and questioned about fellow Fulanis, who the militia said were killing people. He says the men accused them of reporting information to terrorists about planned military assaults.

The teenager showed a reporter a 25-centimeter scar across his back that he says was from the beating.

Requests for comment from Burkina Faso’s military police on the allegations of abuse went unanswered.

Rights groups say the discrimination helps terrorists recruit more fighters, even though the Fulani are suffering the brunt of Islamist attacks.

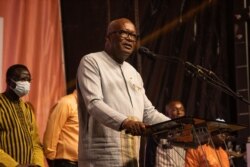

Burkina Faso’s President Roch Kabore, at his December inauguration for a second term, vowed to focus on national reconciliation.

He says over the past five years, Burkina Faso has been the target of armed terrorist groups whose actions have undermined development efforts, social cohesion and the lives of citizens.

But half of Burkina Faso’s population come from its largest ethnic group, the Mossi — farmers who for centuries have held most of the land wealth and, therefore, political power.

Kabore is Mossi, as are 18 out of his 25 newly appointed Cabinet ministers, while only three are Fulani.

Kobore appointed the country’s first minister for national reconciliation, Zephirin Diabre, this month.

Diabre, who is an ethnic Bissa and came third in November’s presidential race, admits access to land wealth is a growing problem.

“The issue of land is now becoming a sort of bomb. In many parts of the country, communities are facing others and fighting for it,” he said.

Diabre says ethnic discrimination is also fueling the tensions.

“If, for instance, in an area, it happens that those who are terrorists, most of them speak Fulani, there’s a tendency for people to say it’s the Fulani who are the issue. We need to educate them.”

Kabore’s ruling People's Movement for Progress party is expected to introduce a roadmap to reconciliation at the end of this month.