An American man, convicted of providing support to the Taliban, has been released from prison.

John Walker Lindh, known as the “American Taliban,” was released from a federal prison in Terre Haute, Ind., Thursday after serving 17 years of a 20-year sentence.

Lindh was captured during the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 in the aftermath of a prison uprising that claimed the life of CIA officer Johnny “Mike” Spann, who was the first American casualty of war in Afghanistan.

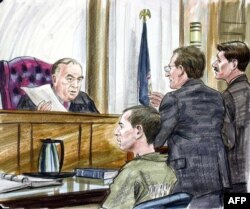

“Given the rare nature of defendant’s crime and his unique personal history and characteristics, the probation officer recently filed a request asking the court to impose additional special conditions of (a) supervised release which will govern the defendant’s behavior post-confinement,” federal Judge T.S. Ellis III wrote in court papers filed earlier in April.

Lindh was tried in federal court.

In 2002, Lindh pleaded guilty to two criminal charges of providing support to the Taliban, and carrying a rifle and grenade.

Judge Ellis has ordered that Lindh won’t have access to the internet without permission from his probation office, can’t view or access extremist or terrorism related videos, and must allow the probation office to monitor his internet use.

Catholicism to Islam

Lindh, 38, converted from Catholicism to Islam when he was 16 years old. He traveled to Yemen at the age of 17 to study Arabic. He then made his way to Pakistan and Afghanistan, where he became a Taliban volunteer at an al-Qaida training camp.

Some analysts charge that Lindh’s case is slightly different from those of other U.S foreign fighters.

“U.S. foreign fighter citizens who go from the United States to join the (Islamic State) caliphate are, in my mind, in a very different category than John Walker Lindh, who went over to South Asia to study Islam and who went to Afghanistan before 9/11 [terror attacks],” said Karen Greenberg, director of Center on National Security at Fordham Law.

“He is not accused of anything related to the attacks of 9/11, so he’s not a foreign fighter. He didn’t go abroad to fight on behalf of the United States’ enemy. He was caught in enemy territory,” Greenberg told VOA in a phone interview.

Objection

Lindh’s early release has raised objections from some U.S. lawmakers who argue that Lindh remains a danger to society.

In addition to Lindh, “as many as 108 other terrorist offenders are scheduled to complete their sentences and be released from U.S. federal prisons over the next few years,” said Senators Richard Shelby, a Republican, and Maggie Hassan, a Democrat, in a joint letter sent last week to Hugh Hurwitz, acting director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

“Little information has been made available to the public about who, when and where these offenders will be released, whether they pose an ongoing public threat, and what federal agencies are doing to mitigate this threat while the offenders are in federal custody,” the lawmakers said.

Threats?

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, chief executive officer of Valens Global, a research firm focused on terrorism and violent extremism, says that serving time and denouncing terrorism aren’t guarantees that individuals like Lindh won’t pose threats upon their release.

“Though people arrested in the United States for terrorism offenses have tended to receive longer prison sentences than European terrorists, Europe provides an example of how people arrested for terrorism offenses can still pose a threat after their release,” he told VOA.

“Many of the European cases involve released prisoners who became involved in extremist recruitment efforts. But they have been involved in attacks as well, with the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack [in France] notorious among them,” Gartenstein-Ross added.

Other experts believe that it is feasible to monitor former convicts to make sure they would not pose any danger to society after their release.

“We have the technology in the United States to monitor people,” said Seth Frantzman, a terrorism expert based in the Middle East.

“In the case of Lindh, we have to see if the government, those who monitored him in prison, think that he is still an extremist threat. He can always be monitored,” he told VOA.

The U.S. “should have rehabilitation programs throughout the criminal justice system. It was a strength of the American criminal justice system at the end of 20th century, but it doesn’t have any of that robustness, it’s not a priority the way it used to be,” analyst Greenberg said.

Zazi’s case

Lindh is not the only case that is renewing the debate over releasing terrorism-related convicts back into society.

In early May, a federal judge in New York said that Najibullah Zazi, who plotted to bomb the New York subway system, will get no additional prison time after prosecutors cited his “extraordinary cooperation” with federal investigators.

In 2010, Zazi pleaded guilty to three charges linked to the plot.

Since then, he has been a helpful cooperator, having met with the government more than 100 times, testified in multiple trials, and “provided critical intelligence and unique insight regarding al-Qaida and its members,” prosecutors said in court filings.

Former IS Members

Dozens of Americans have traveled to Iraq and Syria in recent years to join terror groups such as the Islamic State (IS). With the formal defeat of IS in March, many of those Americans have been captured by the U.S.-backed Kurdish forces.

The Program on Extremism at George Washington University in Washington, has identified 76 Americans who have joined jihadist groups in Iraq and Syria since 2011.

The U.S. government has maintained it will take home its citizens who fought for IS in Iraq and Syria and has encouraged its European partners to follow suit.

“We take all claims of U.S. citizenship by individuals in conflict zones seriously, and work to verify those claims on a case-by-case basis,” a U.S official recently told VOA.

“The United States will continue to repatriate and prosecute its citizens when possible, as we have done in the past,” the official added.

Experts said that seeking to address them on a case-by-case basis is key to ensuring that they will not pose any danger to American society.

“Everyone who joined IS shows that they pose a threat. But they may pose different types of threats,” analyst Frantzman said. “If some of the women that went there wanted just to marry someone, they may pose a threat that they could radicalize other women. A man who used an AK-47 and learned to fight or engaged in war crimes, he poses a different kind of threat.”