Teacher Rishi Rawat has one student who is not human, but a machine.

Lessons take place at a lab inside the University of Southern California’s (USC) Clinical Science Center in Los Angeles, where Rawat teaches artificial intelligence, or AI.

To help the machine learn, Rawat feeds the computer samples of cancer cells.

“They’re like a computer brain, and you can put the data into them and they will learn the patterns and the pattern recognition that’s important to making decisions,” he explained.

AI may soon be a useful tool in health care and allow doctors to understand biology and diagnose disease in ways that were never humanly possible.

Doctors not going away

“Machines are not going to take the place of doctors. Computers will not treat patients, but they will help make certain decisions and look for things that the human brain can’t recognize these patterns by itself,” said David Agus, USC’s professor of medicine and biomedical engineering, director at the Lawrence J. Ellison Institute for Transformative Medicine, and director at the university’s Center for Applied Molecular Medicine.

Rawat is part of a team of interdisciplinary scientists at USC who are researching how AI and machine learning can identify complex patterns in cells and more accurately identify specific types of breast cancer tumors.

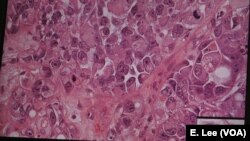

Once a confirmed cancerous tumor is removed, doctors still have to treat the patient to reduce the risk of recurrence. The type of treatment depends on the type of cancer and whether the tumor is driven by estrogen. Currently, pathologists would take a thin piece of tissue, put it on a slide, and stain with color to better see the cells.

“What the pathologist has to do is to count what percentage of the cells are brown and what percentage are not,” said Dan Ruderman, a physicist who is also assistant professor of research medicine at USC.

The process could take days or even longer. Scientists say artificial intelligence can do something better than just count cells. Through machine learning, it can recognize complicated patterns on how the cells are arranged, with the hope, in the near future of making a quick and more reliable diagnosis that is free of human error.

“Are they disordered? Are they in a regular spacing? What’s going on exactly with the arrangement of the cells in the tissue,” described Ruderman of the types of patterns a machine can detect.

“We could do this instantaneously for almost no cost in the developing world,” Agus said.

Computing power improves

Scientists say the time is ripe for the marriage between computer science and cancer research.

“All of a sudden, we have the computing power to really do it in real time. We have the ability of scanning a slide to high enough resolution so that the computer can see every little feature of the cancer. So it’s a convergence of technology. We couldn’t have done this, we didn’t have the computing power to do this several years ago,” Agus said.

Data is key to having a machine effectively do its job in medicine.

“Once you start to pool together tens and hundreds of thousands of patients and that data, you can actually [have] remarkable new insight, and so AI and machine learning is allowing that. It’s enabling us to go to the next level in medicine and really take that art to new heights,” Agus said.

Back at the lab, Rawat is not only feeding the computer more cell samples, he also designs and writes code to ensure that the algorithm has the ability to learn features unique to cancer cells.

The research now is on breast cancer, but doctors predict artificial intelligence will eventually make a difference in all forms of cancer and beyond.