Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump set off a political firestorm Monday when he called for at least temporarily barring Muslims from entering the United States – even U.S. citizens trying to return from travels outside the country. Earlier, fellow GOP candidate Ted Cruz proposed accepting for U.S. resettlement only those Syrian refugees who are Christian.

But could the nation's chief executive legitimately order such actions, even with congressional approval?

"It violates the Constitution. It’s discrimination on the basis of religion, which is prohibited by the Constitution," said Suzanna Sherry, a professor at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee.

Trump's plan is "a troubling proposal," also potentially breeching the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause, said Kevin R. Johnson, dean of the law school at the University of California, Davis. "It’s really amazing in its breadth and hostile in its unconstitutionality."

"Our entire legal and regulatory system is based on nondiscriminatory policy," said Jonathan Turley. The George Washington University legal scholar wrote in his blog Tuesday that Trump’s call for a "total and complete shutdown" of Muslims entering the United States "would violate a host of domestic and international protections." And, he told VOA, "Instead of being a country that has long defended religious freedom, we would become the scourge of religious freedom."

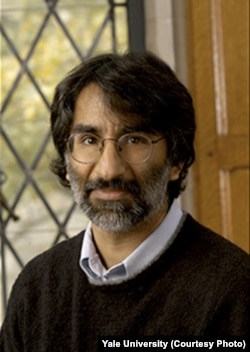

"Donald Trump is dividing us along religious lines. That’s un-American," added Akhil Reed Amar, a Yale University law professor.

They were among the constitutional scholars who weighed in with VOA on Tuesday, a day after billionaire real estate developer Trump issued a statement urging a ban on Muslims’ entry "until our country's representatives can figure out what is going on." It followed terrorist attacks last week in California and last month in Paris.

"Large segments of the Muslim population" have expressed "great hatred" toward Americans, Trump said, reiterating his calls for suspending access both at a South Carolina campaign rally later Monday and on multiple U.S. news talk shows Tuesday.

His remarks drew widespread condemnation, including from House Speaker Paul Ryan and other prominent Republicans seeking to distance themselves and their party from Trump.

But U.S. Senator Cruz of Texas held a news conference Tuesday to "commend Donald Trump for standing up and focusing America’s attention on the need to secure our borders."

Cruz acknowledged he disagreed with Trump’s plan and highlighted his own. Accompanied by Texas’ Republican governor, Greg Abbott, the senator announced he’s introducing a bill that would let governors opt out of refugee resettlement in their respective states if they believed advance screening was insufficient to ensure public safety. Cruz already has introduced legislation calling for a three-year moratorium on accepting refugees from countries where the Islamic State group operates.

Sherry, the Vanderbilt professor, said she "wasn’t particularly astonished" by Trump’s position because "he’s suggested a number of unconstitutional actions before…. He thinks you can get rid of birthright citizenship," she reminded, citing his comments in summer. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, grants automatic citizenship to any child born on U.S. soil.

Cruz "is much more careful" than Trump, Yale’s Amar said of the Canadian-born Texas lawmaker. "He’s not proposing a religious test. He’s saying we must look closely at people from certain countries."

US immigration history

U.S. immigration laws long have differentiated among potential newcomers based on their nations of origin.

"We do not have the best history when it comes to this country,” said UC-Davis’ Johnson, author of "The Huddled Masses Myth," a book about U.S. immigration and civil rights. "In some ways, you could view this as a revival of the now-discredited Chinese exclusion laws."

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first of several legislative maneuvers to block Chinese immigrants. Later, the Immigration Act of 1924 created quotas that favored white Europeans over people from Asia and Africa, a policy curtailed in 1965. In subsequent decades, the U.S. government, fighting Soviet-style communism, welcomed Cubans as political refugees but discouraged Haitians as economic refugees, because "it was important for us to repudiate a communist regime on our doorstep," Amar said.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the U.S. government in 2002 and 2003 required male noncitizens 16 and older to register with the Immigration and Naturalization Service if they’d come from one of 25 countries with predominantly Muslim populations. The program ended after the INS was absorbed by the Department of Homeland Security.

"Countries can create special systems for reviewing applications … or entries from particular regions," Turley said. A nation has "a right to review entries to make sure that not only its own borders are secure" but that it's not assisting criminals from escaping justice, especially from a conflict zone "ravaged by human rights violations."

"What Mr. Trump is suggesting is something that’s far more arbitrary, far more capricious and far more dangerous," Turley said. "He’s suggesting that religion alone" should be the determining factor in barring U.S. entry.

Spectrum of protections

Constitutional protections vary based on an individual’s status, Turley said. Those with the greatest are U.S. citizens, and "any effort to prevent Muslim [American] citizens from returning to the country would be flagrantly unconstitutional." Aside from encroaching on the First Amendment’s safeguard of religious freedom, it would violate the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition against depriving a person of "life, liberty or property."

Protections gradually diminish: from U.S. residents with legal status – so-called "green card" holders – to unauthorized residents to noncitizens living abroad. But even the latter, while having few protections under constitutional law, "may have claims under international law," Turley said. It prohibits religious discrimination and "also recognizes the right to travel by different groups and individuals."

Problems at home and abroad

Turley also noted that individuals working for or contracted by the U.S. government, such as U.S. embassy personnel, "are required to meet nondiscriminatory policies" even while abroad. Trump’s plan "of sorting out Muslims" would "create a host of interstitial conflicts" within U.S. government bureaucracies.

"It would also put us at odds not just with international law but the international community," Turley added. The European Union, for instance, is "governed by anti-discrimination policies. We would put our closest allies in a difficult position…. We’d become a perfect pariah in the international community."

And at home in America, Trump’s comments create more hostility toward Muslims, Johnson said.

"There’s a palpable fear among the Muslim community in the United States about their treatment, and these kinds of statements – whether he’s just trying to get attention or not – [have] a real impact on people."

Yale’s Amar – the American-born son of immigrants from India – acknowledged the need to protect U.S. borders. But, he said, "it’s a real mistake to scapegoat American Muslims, the world’s Muslims, most of whom are helping us in the war against radical Islam."

Turley offered a final thought on Trump’s plan for religious screening, which he called "a real paper tiger of a border defense."

"Someone who is willing to enter the country to commit terrorist attacks would not be appalled at the thought of lying about his religion," Turley said. "… I have a feeling you would have a dramatic increase in Quakers" – whose faith promotes nonviolence – "coming across the border from the Middle East."