China’s increasing naval power, the country having surpassed the United States as the world’s largest maritime force, is giving Beijing crucial sway in negotiations with Asian governments that dispute its claims at sea, experts say.

The U.S. Defense Department, in its September annual report to Congress on military and security developments involving China, said China’s navy ranks as the world’s biggest in numerical terms. The report calls the People’s Liberation Army Navy an “increasingly modern and flexible force” armed with “modern multi-role combatants.”

China’s navy has avoided war, a potential battlefield disadvantage, but its size means Chinese leaders can get their way in talks with other Asian countries, analysts in the Asia Pacific region say.

“It certainly doesn’t hurt to have a powerful navy when you go into diplomatic negotiations and say, ‘Give us what we want and then we’ll think about what else we want,’” said Malcolm Davis, senior analyst in defense strategy and capability at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra.

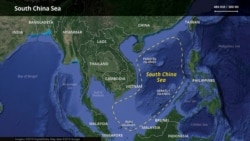

Five other Asian governments dispute Beijing’s reach in the resource-laden South China Sea and want Beijing to sign a code of conduct that would reduce the risk of accidents. Beijing disputes parts of the East China Sea with Japan and Taiwan – and claims sovereignty over Taiwan itself.

China’s navy grew through what the Defense Department report described as a “robust shipbuilding and modernization program.” The fleet now includes submarines, amphibious warfare ships and aircraft carriers as well as capability to use “advanced weapons,” the report said.

As of 2012, the Chinese navy had 512 ships, according to Britain’s International Institute of Strategic Studies. It now has 777 assets, mainly seafaring vessels, the database Globalfirepower.com says. Total U.S. assets number 490.

“Some countries, for example Vietnam, that will be worried, and Taiwan has got to be worried, no issue there,” said Huang Kwei-bo, vice dean of the international affairs college at National Chengchi University in Taipei.

Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam claim all or parts of the South China Sea. Vietnam clashes periodically with China, including a boat-ramming incident in 2014. Taiwan spots Chinese military aircraft almost daily flying through a corner of its air defense identification zone.

Beijing says 90% of the 3.5 million-square-kilometer South China Sea falls under its flag and cites historical usage records to support that claim. The sea is prized for fisheries, undersea fuel reserves and marine shipping lanes. China has landfilled some of the sea’s tiny islets for military infrastructure, outraging the other claimants but prompting no follow-up military action.

The 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations is pressing China for the maritime code of conduct because having rules would benefit the militarily weaker ASEAN countries. Any such document, however, will also favor China’s demands, such as omitting a third-party arbitrator in incidents that come up and leaving it vague what is considered the South China Sea, analysts predict. A code has been on the table since 2002.

“China can basically go into diplomatic negotiations over disputes such as the South China Sea and say, ‘We’ll take what we want and you can’t do anything about it’, and you’re seeing that now with the code of conduct, where the ASEAN states have essentially given China everything it wants,” Davis said.

The navy’s strength will further pressure other South China Sea claimants to “behave” as China wants, said Jay Batongbacal, international maritime affairs professor at University of the Philippines. In Manila, he said, President Rodrigo Duterte periodically warns of China’s military strength as a reason to engage it rather than pushing too hard over disputed maritime claims.

“The Duterte administration is always sort of pointing to the strength of China, so the increasing size of their navy is just another argument that they will make in order to justify their positions and their accommodations to China,” Batongbacal said.

Duterte’s predecessor, former President Benigno Aquino III, filed for World Court arbitration against China in 2013 and three years later the court ruled that China lacked a legal basis for its maritime claims. China rejected the ruling and reached out to Duterte with economic aid.

Southeast Asian countries and Taiwan traditionally tap the United States for help. The U.S. Navy sent ships to the South China Sea 10 times in 2020 as warnings to China. Washington separately sells arms to Taiwan and trains troops in the Philippines.

China and Japan agreed last year to start working-level talks on the East China Sea including a chain of disputed Japanese-controlled islets, as Tokyo answers growing Chinese naval strength by fortifying other islands with anti-ship missile batteries.

Japan is nervous about China’s naval expansion but for now has enough of its own maritime experience to keep its head up at the bargaining table, said Jeffrey Kingston, a history instructor at the Japan campus of Temple University. In 10 years, he said, China might be more willing to take on Japan’s naval forces.