Britain is facing a dilemma with China.

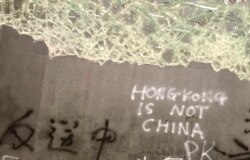

Should it champion the rights and freedoms of the people of Hong Kong enshrined in a joint declaration signed with Beijing before the British handed the territory back to the Chinese in 1997, ending 156 years of colonial rule?

Or should it muffle its complaints about Chinese heavy-handedness — or breaches of the joint declaration — in order to ingratiate itself with China and reap commercial benefits?

Diplomatic balancing act crumbles

For the past year, as a trade war erupted between Beijing and Washington, and criticism mounted in Brussels of China being a “strategic competitor,” Britain has sought to keep its balance on a diplomatic high-wire, falling neither to one side or the other.

But midweek it lost balance.

London and Beijing are now embroiled in a full-scale diplomatic quarrel following mass protests in Hong Kong against a now suspended bill that would have allowed extradition to mainland China. Pro-democracy activists say extradition would be used against dissidents in Britain’s former colony.

In an escalating war of words British and Chinese officials are dueling with both sides warning of serious consequences.

The skirmishing came after Britain’s foreign secretary, Jeremy Hunt, urged China to abide by the Sino-British Joint Declaration that governed the return of Hong Kong. The declaration guaranteed freedoms for at least half-a-century in the former British colony not enjoyed in mainland China, including the right to protest under a model of governance known as “one country, two systems.”

The timing of Hunt’s intervention earlier this week was unfortunate. His initial comments were designed to coincide with the 22nd anniversary of the British handover of Hong Kong to China. It was focused on last month’s mass demonstrations and the rough police handling of those protests. But it came several hours before a breakaway group of pro-democracy agitators stormed and wrecked Hong Kong’s Legislative Council chamber.

The British sought quickly to distance themselves from violent protesters, without giving ground on the broader issue of governance and democracy in Hong Kong.

Harsh words from Chinese envoy

The Chinese envoy to Britain called a rare press conference on Wednesday to denounce Britain for “gross interference” in internal Chinese matters and in the process issued thinly-disguised threats, saying Sino-British relations had already been damaged, trust weakened and that unless Britain stopped meddling, then there would be serious repercussions.

“In the minds of some people, they regard Hong Kong as still under British rule. They forget ... that Hong Kong has now returned to the embrace of the Motherland,” Liu Xiaoming, said. “I tell them: hands off Hong Kong and show respect. This colonial mindset is still haunting the minds of some officials or politicians,” Liu told reporters.

He and officials in Beijing accused Britain of embracing “violent law-breakers.”

The envoy’s robust words earned him a formal reprimand from the British foreign ministry when he was summoned to explain himself. Hunt tweeted later to the Chinese government “good relations between countries are based on mutual respect and honoring the legally binding agreements between them.”

Bad economic timing

The quarrel is ill-timed for Britain, which is desperate to boost its trade with China post-Brexit in order to make up for the likely economic losses incurred from relinquishing European Union membership.

Since a spat between London and Beijing last year over the disputed South China Sea, British officials have been working feverishly to reset Sino-British relations.

Some analysts suspect Downing Street’s provisional decision in April to allow the technology giant Huawei a role in building parts of Britain's 5G mobile network, overriding U.S. security objections in the process, was dictated by this Brexit-related diplomatic charm offensive towards China.

The visit to the British capital last month by Chinese Vice Premier Hu Chunhua, for the inauguration of a link between the London stock exchange and Shanghai’s, was seen as an important step by British officials. But the Hong Kong issue is throwing a wrench into the British diplomatic offensive. Analysts say Britain on its own has little leverage and much to lose by confronting China.

Britain hardly alone in its China problem

The dilemma Britain faces mirrors that of other Western countries, who are also asking how best to manage China, a rising power they’re eager to do business with but one that bristles at criticism, doesn’t share the liberal values of the West’s democracies and is demanding a greater role in global governance.

Some Western governments, including those in Italy and Hungary, both run by populists, have decided there is no dilemma. Rome and Budapest have signed on to China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious trillion-dollar transcontinental trade and infrastructure project that critics, including U.S. and EU officials, worry is aimed at boosting Beijing's growing political clout in Europe.

But for Britain, with the Hong Kong issue thrown in, the quandary about how to approach China is especially complicated. As a co-signatory to the declaration governing the handover of Hong Kong, it can hardly stifle its concerns about the governance of its former colony without losing reputation, risking prestige and being seen as a fair-weather friend of Western liberal values, say analysts.

Even before this latest flare-up in Hong Kong, British governments seemed not to have hit on a solution to the China problem. In April, the British parliament’s foreign affairs committee said it couldn’t identify a coherent government policy and accused policy-makers of being unwilling to face the reality that China is both a viable economic partner, but also a “challenger,” whose “foreign policy is shaped by the need to serve the interests and perceived legitimacy of the Communist Party.”

It urged a recalibration that doesn’t prioritize “economic considerations over other interests, values and national security.” That is easier said than done.