CAIRO —

Millions hope so, it seems; they have signed a national petition demanding the president resign and plan to take to the streets on June 30, when Mohamed Morsi marks a year in office.

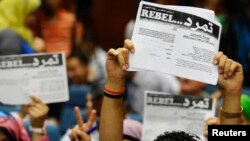

Their slogan is a call for revolt: “Tamarud - Rebel!”

But for all the simmering discontent with the Islamist who has presided over political and economic paralysis, millions more are ready to defend Egypt's first freely elected leader; they say those campaigning for him to quit are agents of the old regime and plan their own pro-Morsi rallies starting Friday.

Their counter-campaign - “Tagarud” - calls for open minds.

There is a risk of more of the violence that has punctuated the two-and-a-half years since Hosni Mubarak was toppled by a blast of rage from Tahrir Square. “June 30” crops up endlessly in conversation. The Cairo bourse has shriveled in anticipation and security forces say they are preparing to deal with trouble.

“There is a strong chance of violence resulting from the coming protests,” said retired Egyptian general Sameh Seif al-Yazal, a military analyst. “It could start from any side.”

It is unclear what can end stalemate between the Islamists, whose organized electoral base has handed them the formal levers of power, and a diffuse opposition of liberals, Christians and secular conservatives united in fear of Islamic rule, plus a mass of the uncommitted fed up with economic drift under Morsi.

The “culture war” between elected Islamists and a secular opposition, with a once-political army in the background, has echoes of today's unrest in Turkey, but deep economic crisis and a still unformed political system makes Egypt much more fragile.

With world powers at odds over Syria, where Morsi has backed the Sunni Muslim revolt, and Washington funding an Egyptian army that honors Cairo's peace treaty with Israel, any instability in the most populous Arab state has implications far beyond.

The wealthy generals, once led by Mubarak but who sacrificed him to save themselves, have said they want no more political role. Islamists say it would mean civil war if the troops moved against them. Yet the army is still held in high regard by the vast majority and says it will intervene to maintain order.

However June 30 ends - and few will bet with confidence on the outcome - it will help determine whether the Arab Spring eventually blossoms, or withers - not just for 84 million Egyptians but for would-be democracies across the Middle East.

Unfinished Revolution

“This revolution is not over yet,” said Mohamed ElBaradei, a former top U.N. diplomat and one of the best known faces of Tamarud, whose keen young sidewalk volunteers say their petition is close to gathering more signatures for Morsi's - hypothetical - removal than the 13 million votes that elected him a year ago.

ElBaradei spoke at a two-week-old sit-in by artists at the Culture Ministry. It was prompted by the new minister firing the head of Cairo Opera and by fears of a new puritanism after an Islamist lawmaker called for a ban on ballet as “naked art”.

Such threats capture media headlines and ElBaradei said Islamist dominance must be stopped: “We ask every Egyptian to go out on the 30th, to free ourselves and reclaim our revolution.”

For the millions of poor, for whom the ballet ranks low on their priorities, it is an economy caught in a vice of collapsed tourist income, rising world commodity prices and a growing population dependent on subsidized bread and fuel that matters.

“We don't want Morsi. We want change,” said Umm Sultan, working with her son at the family juice stall in Cairo's Old City. “They must give us money so our children can live.”

Echoing fellow Islamists governing in Turkey, Morsi's Muslim Brotherhood insists he has a democratic mandate and warn that protest is permitted - “a healthy sign that this revolution has actually worked”, one aide called it - but must be peaceful.

Morsi himself says he will react “fiercely” to trouble from “felloul” - 'remnants' of Mubarak - and calls the petition, which has no legal weight, “an absurd and illegitimate action”.

There have been scuffles this month between groups gathering signatures; an apartment used by Tamarud was firebombed. A new test looms this Friday, when Islamists plan pro-Morsi rallies.

The heart of the problem is a failure to build consensus.

With opponents in disarray, the Brotherhood and its allies won majorities in both houses of parliament and the presidency last year and rushed a constitution through a referendum. The opposition, partly backed by a judiciary the Islamists see as Mubarak holdovers, now reject most of those state institutions.

Elections for a new lower house that might provide a forum for national dialog are being held up by rows over the rules.

Anchoring his power in the provinces, Morsi named Islamists to run several governorates on Sunday, including one from a group whose gunmen massacred 58 foreigners in Luxor and will now head the administration in the temple city, a hub for tourism.

Deprived of broad popular support, the legislature and the executive have struggled to act decisively on the economy.

Islamists Warn Army

There seems little prospect the Tamarud petition will induce Morsi to resign - and even some liberal commentators say that might set an unwelcome precedent. Morsi's win seemed fair and a new presidential vote might produce a broadly similar result.

No opponent is clearly more popular than the bespectacled, bearded face crossed out with a red “X” on Tamarud's ubiquitous posters. Yet if the protest movement seems like a leap into the unknown, that is not deterring large numbers from joining it.

“Tamarud is a representative public reaction to the Muslim Brotherhood and Morsi's failure to run the state,” said Hassan Nafaa, a Cairo University political scientist who says Morsi must resign for his “stupidity”. “It has left people no option but the streets and so they will come out - in large numbers.”

The president's allies will not give in so easily.

“If Morsi ends up being ousted by violence or a coup by the army or police, there will be an Islamic revolution,” said Al-Ghaddafi Abdel Razek, manager of the pro-Morsi Tagarud campaign.

“We have our people in the army and the police, too, and we are ready,” added Abdel Razek, 37, a pharmacist once jailed for his membership of al-Gamaa al-Islamiya, the militant group that tried to cripple Mubarak by attacking tourists in the 1990s.

Tagarud's gathering of seven million signatures urging Morsi to stay is also deeply personal.

“We know that if Morsi goes, we'll all be in prison,” Abdel Razak said.

Decision Time

Over at the opposition campaign, spokesman Mahmoud Badr is grappling with piles of signatures and ID numbers that need to be verified against databases if Tamarud is to make the case it hopes to the United Nations that its petition is genuine.

Even without international intervention, Badr argued, the weight of opinion could embarrass Morsi into stepping aside. Others say that at least it might push him to listen to them.

And after that? It may seem hypothetical now, but Badr and his team have a post-Morsi plan: the constitutional court chief would be interim head of state with a small technocrat cabinet.

For many, exasperated by power cuts, shortage of fuel and rising prices, a return to army rule would be welcome - though the military insists it wants no such responsibility. Its chief, appointed by Morsi, has urged “a framework for consensus”.

One military source told Reuters the army was ready for all eventualities after June 30 - “but we will not interfere unless the situation seems to be heading towards violent conflict”.

Army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has said troops will “defend the state and what is sacred to the people” - that, the source said, included their rights to protest.

As the rallies approach, Egyptians have decisions to make.

Ahmed Mahmoud, 30, a laborer from Alexandria is already in the capital to make his voice heard.

“I want to tell Morsi loud and clear he needs to go since he has failed to meet the demands of our revolution, for a better life and freedom,” he said.“We are tired and cannot take it any more. We want to live.”

But others, who fear yet more unrest can only plunge them deeper into poverty, are more patient. Mohamed Ali, 26, a waiter at a Cairo cafe, said Morsi should be given his chance: “We are new to democracy and we should give him time to work and learn.”

Their slogan is a call for revolt: “Tamarud - Rebel!”

But for all the simmering discontent with the Islamist who has presided over political and economic paralysis, millions more are ready to defend Egypt's first freely elected leader; they say those campaigning for him to quit are agents of the old regime and plan their own pro-Morsi rallies starting Friday.

Their counter-campaign - “Tagarud” - calls for open minds.

There is a risk of more of the violence that has punctuated the two-and-a-half years since Hosni Mubarak was toppled by a blast of rage from Tahrir Square. “June 30” crops up endlessly in conversation. The Cairo bourse has shriveled in anticipation and security forces say they are preparing to deal with trouble.

“There is a strong chance of violence resulting from the coming protests,” said retired Egyptian general Sameh Seif al-Yazal, a military analyst. “It could start from any side.”

It is unclear what can end stalemate between the Islamists, whose organized electoral base has handed them the formal levers of power, and a diffuse opposition of liberals, Christians and secular conservatives united in fear of Islamic rule, plus a mass of the uncommitted fed up with economic drift under Morsi.

The “culture war” between elected Islamists and a secular opposition, with a once-political army in the background, has echoes of today's unrest in Turkey, but deep economic crisis and a still unformed political system makes Egypt much more fragile.

With world powers at odds over Syria, where Morsi has backed the Sunni Muslim revolt, and Washington funding an Egyptian army that honors Cairo's peace treaty with Israel, any instability in the most populous Arab state has implications far beyond.

The wealthy generals, once led by Mubarak but who sacrificed him to save themselves, have said they want no more political role. Islamists say it would mean civil war if the troops moved against them. Yet the army is still held in high regard by the vast majority and says it will intervene to maintain order.

However June 30 ends - and few will bet with confidence on the outcome - it will help determine whether the Arab Spring eventually blossoms, or withers - not just for 84 million Egyptians but for would-be democracies across the Middle East.

Unfinished Revolution

“This revolution is not over yet,” said Mohamed ElBaradei, a former top U.N. diplomat and one of the best known faces of Tamarud, whose keen young sidewalk volunteers say their petition is close to gathering more signatures for Morsi's - hypothetical - removal than the 13 million votes that elected him a year ago.

ElBaradei spoke at a two-week-old sit-in by artists at the Culture Ministry. It was prompted by the new minister firing the head of Cairo Opera and by fears of a new puritanism after an Islamist lawmaker called for a ban on ballet as “naked art”.

Such threats capture media headlines and ElBaradei said Islamist dominance must be stopped: “We ask every Egyptian to go out on the 30th, to free ourselves and reclaim our revolution.”

For the millions of poor, for whom the ballet ranks low on their priorities, it is an economy caught in a vice of collapsed tourist income, rising world commodity prices and a growing population dependent on subsidized bread and fuel that matters.

“We don't want Morsi. We want change,” said Umm Sultan, working with her son at the family juice stall in Cairo's Old City. “They must give us money so our children can live.”

Echoing fellow Islamists governing in Turkey, Morsi's Muslim Brotherhood insists he has a democratic mandate and warn that protest is permitted - “a healthy sign that this revolution has actually worked”, one aide called it - but must be peaceful.

Morsi himself says he will react “fiercely” to trouble from “felloul” - 'remnants' of Mubarak - and calls the petition, which has no legal weight, “an absurd and illegitimate action”.

There have been scuffles this month between groups gathering signatures; an apartment used by Tamarud was firebombed. A new test looms this Friday, when Islamists plan pro-Morsi rallies.

The heart of the problem is a failure to build consensus.

With opponents in disarray, the Brotherhood and its allies won majorities in both houses of parliament and the presidency last year and rushed a constitution through a referendum. The opposition, partly backed by a judiciary the Islamists see as Mubarak holdovers, now reject most of those state institutions.

Elections for a new lower house that might provide a forum for national dialog are being held up by rows over the rules.

Anchoring his power in the provinces, Morsi named Islamists to run several governorates on Sunday, including one from a group whose gunmen massacred 58 foreigners in Luxor and will now head the administration in the temple city, a hub for tourism.

Deprived of broad popular support, the legislature and the executive have struggled to act decisively on the economy.

Islamists Warn Army

There seems little prospect the Tamarud petition will induce Morsi to resign - and even some liberal commentators say that might set an unwelcome precedent. Morsi's win seemed fair and a new presidential vote might produce a broadly similar result.

No opponent is clearly more popular than the bespectacled, bearded face crossed out with a red “X” on Tamarud's ubiquitous posters. Yet if the protest movement seems like a leap into the unknown, that is not deterring large numbers from joining it.

“Tamarud is a representative public reaction to the Muslim Brotherhood and Morsi's failure to run the state,” said Hassan Nafaa, a Cairo University political scientist who says Morsi must resign for his “stupidity”. “It has left people no option but the streets and so they will come out - in large numbers.”

The president's allies will not give in so easily.

“If Morsi ends up being ousted by violence or a coup by the army or police, there will be an Islamic revolution,” said Al-Ghaddafi Abdel Razek, manager of the pro-Morsi Tagarud campaign.

“We have our people in the army and the police, too, and we are ready,” added Abdel Razek, 37, a pharmacist once jailed for his membership of al-Gamaa al-Islamiya, the militant group that tried to cripple Mubarak by attacking tourists in the 1990s.

Tagarud's gathering of seven million signatures urging Morsi to stay is also deeply personal.

“We know that if Morsi goes, we'll all be in prison,” Abdel Razak said.

Decision Time

Over at the opposition campaign, spokesman Mahmoud Badr is grappling with piles of signatures and ID numbers that need to be verified against databases if Tamarud is to make the case it hopes to the United Nations that its petition is genuine.

Even without international intervention, Badr argued, the weight of opinion could embarrass Morsi into stepping aside. Others say that at least it might push him to listen to them.

And after that? It may seem hypothetical now, but Badr and his team have a post-Morsi plan: the constitutional court chief would be interim head of state with a small technocrat cabinet.

For many, exasperated by power cuts, shortage of fuel and rising prices, a return to army rule would be welcome - though the military insists it wants no such responsibility. Its chief, appointed by Morsi, has urged “a framework for consensus”.

One military source told Reuters the army was ready for all eventualities after June 30 - “but we will not interfere unless the situation seems to be heading towards violent conflict”.

Army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has said troops will “defend the state and what is sacred to the people” - that, the source said, included their rights to protest.

As the rallies approach, Egyptians have decisions to make.

Ahmed Mahmoud, 30, a laborer from Alexandria is already in the capital to make his voice heard.

“I want to tell Morsi loud and clear he needs to go since he has failed to meet the demands of our revolution, for a better life and freedom,” he said.“We are tired and cannot take it any more. We want to live.”

But others, who fear yet more unrest can only plunge them deeper into poverty, are more patient. Mohamed Ali, 26, a waiter at a Cairo cafe, said Morsi should be given his chance: “We are new to democracy and we should give him time to work and learn.”