This week, Iranians will select a new parliament and Assembly of Experts in twin elections that many Western analysts regard as a defining moment in Iran, one which will test the country’s openness to reform and the future of the nuclear deal. But, some observers close to Iran believe that regardless of whether reformists or conservatives come to power, the ultimate power holders in Iran will remain unchallenged.

The elections taking place Friday are significant for two reasons: First, in the aftermath of the nuclear deal, President Hassan Rouhani is hoping for a parliament that will support his desire to open up Iran’s economy up to foreign investment and trade—not to mention uphold its end of the deal, now that its assets have been released and most sanctions lifted.

Second, the Assembly of Experts, whose chief job is to monitor, dismiss and elect Iran’s Supreme leaders, may get their chance to name a successor to the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is elderly and said to be in poor health.

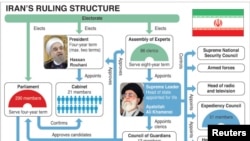

But even if moderates do realize a victory in Friday’s vote, analysts doubt they will be able to usher in any meaningful reforms. To understand why, one only needs to examine some key elements of Iran’s political structure.

Top down management

The Supreme Leader, Iran’s top political and religious leader, is tasked with safeguarding the theocracy formed by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1979. His successor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, controls all branches of the government, the military and the press, and has final say on foreign policy, military and security matters and Iran’s nuclear policy.

The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are, in essence, an ideological army originally created to protect the supreme leader from foreign intervention or a military coup. Over time, the IRGC have evolved into a powerful force that permeates all aspects of Iran’s society, politics and economy, both over- and underground. They are believed to control a big chunk of the country’s GDP.

The Guardian Council is made up of six religious jurists appointed by the supreme leader and six lay clerics named by the head of the judiciary, who himself is appointed by the supreme leader. The Guardians decide who may or may not run for office, and because the supreme leader can dismiss any of them at will, they are perceived as his “yes men” -- or, as Khamenei himself put it, the government’s “seeing eye.”

The Assembly of Experts is a group of 80 Islamic scholars whose chief job is to monitor, dismiss and elect Iran’s Supreme leaders.

“Because they are vetted by the Guardian Council, they can be seen to have been indirectly appointed by the supreme leader,” noted Iranian-American political scientist Majid Rafizadeh. “And the Guardian Council only vets candidates based on their religious authority and their loyalty and fidelity to the supreme leader.”

Parliament, the 290-seat body that drafts laws, ratifies treaties, and supervises government spending. Parliament has some wiggle room on policy, said Rafizadeh, but it basically looks to the supreme leader on fundamental policies.

“And when the Supreme Leader favors a policy, regardless of whether the Parliament is moderate or reformist or hardline, it goes along with the Supreme Leader, because that’s just how the system works,” he added.

The president, the highest-elected leader in Iran, heads the executive branch of the government, the national security council and the council of cultural revolution, which is tasked with preserving religious nature of the Islamic Republic.

“It has been the rule in Iranian politics that once a president is elected, he wants to put some distance between himself and the supreme leader because after all, he cannot ignore a rather sizeable segment of the Iranian public that wants to have more reformist policies adapted,” said Mehrzad Boroujerdi, professor and chair of the political science department at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

That said, Rouhani ultimately answers to the supreme leader and is mindful of the fact that parliament has the power to recommend a president’s removal from office.

Vote rigged from outset?

The Guardian Council this month eliminated half of the roughly 12,000 candidates who signed up to run for the Assembly and parliament, most of them moderates. Given this and the power configuration in Iran, Boroujerdi said he doesn’t expect much to change.

“At best, I expect the reformists will be a small minority within the parliament, but not necessarily a force that is going to be facilitating what President Rouhani really wishes for,” he said.

Indeed, say experts, getting what he wishes for could ultimately hurt him.

Consider what happened to former reformist president Mohammad Khatami, who was elected for two consecutive terms on promises of more jobs, more freedoms and a free market.

“The reformists took over the parliament, and the next thing you know, the IRCG, basij [paramilitary] and police, they shut down newspapers, they shot at point blank range the political strategies of Khatemi, and they just silenced him,” said Harvard scholar Majid Rafizadeh.

Later, the government accused Khatemi of “sedition” and has since banned him from appearing in the media, speaking in public or leaving the country.

The media ban, however, did not stop Kahtemi from issuing a video message on YouTube this week in which, speaking Farsi, he urged voters to select reformist candidates, saying that "the more the people participate in the elections and the more enthusiastically different ideologies are represented, the closer the elections will be to the people's will, the interests of the country, and the people's goals." (Below):

Nor does there appear much chance that the Assembly of Experts, if given the chance this term, will name a reformist Supreme Leader. That decision, said Boroujerdi, may already have been made.

“If we accept the premise of the argument that the current supreme leader is a micromanager, my sense is that he might have handpicked his successor and might therefore tell the Assembly of Experts, ‘here are my last wishes,’” Boroujerdi said. “Just like you saw with Ayatollah Khomeni when he passed away -- he basically had already suggested the Khamenei as his successor.”