In late December, while taking an exam at a University of Nairobi campus in Kabete, Kenya, a prisoner serving a life sentence for a violent robbery escaped.

Peter Kamau Ndungu, an inmate at Naivasha Maximum Prison, had been studying for a bachelor’s degree in commerce. The prison helped arrange for his education and it was not unusual for guards to escort him off-site.

"He went into the classroom like he had done for two years," said Patrick Mwenda, officer in charge of Naivasha Prison.

"Usually, the guards used to wait for him outside, and it has not been a problem really," Mwenda continued. "But that day, he decided to do the opposite. He took off."

Mwenda said he was "annoyed" by the escape.

For one thing, Ndungu was not an ordinary prisoner. He was a model inmate, a star student who tutored others in accounting and who volunteered in the prison’s administrative office when the resident accountant got stuck.

Mwenda and the other officers even organized a "harambee" – a traditional Kenyan fundraising event – along with Ndungu’s family to help pay for his studies.

It raised 400,000 Kenyan shillings, the equivalent of $4,380. "That’s not a little money in our country," Mwenda said.

While it may seem natural for an inmate to take advantage of an easy opportunity to escape the confines of prison, Ngundu’s choice seemed rash. He was making the most of his time behind bars and, more importantly, he may have been on the path to a legitimate pardon.

Claim of innocence

In October, during a VOA visit to Naivasha for a report on the prison’s education program, almost every officer and inmate mentioned Ndungu as a proud example of what Kenyan prisoners can achieve.

When he was approached for an interview, he was sitting at a desk in the library, helping another inmate with his accounting studies.

Amid the clamor of the adjacent prison schoolhouse, Ndungu seemed an especially quiet and studious man, soft-spoken and somewhat melancholy.

"Since my childhood," Ndungu said, "I had an ambition to pursue a course in accounting and finance."

A self-described "peasant" whose father was a pastor, Ndungu had little money to pursue a serious education – but was committed to the dream nonetheless. Then something happened to derail his progress, the crime that would put him away for life.

"You know, that is the most painful part of my story," he said. "I came here because of something I didn’t do.”

Falsely accused of robbery?

As Ndungu told it, in 1999 the police came to his neighborhood in the area of Thika seeking the culprit of an armed robbery. A car used in the crime was found on his family’s property and the cops rounded up all the young men living nearby, including Ndungu.

He said those who were able to pay off the police were let go.

"If you have money, you get freed. You don’t have money, you get convicted. That’s how it happened," he said.

It is difficult to corroborate Ndungu’s version of events, but Nairobi High Court lawyer Donald Rabala said nothing about his account sounds unusual.

"It doesn’t surprise me. This is Kenya for you; this is the police for you. Once an offense is committed, they have to find someone," he said. "You give them a little money and they will walk away, they will pin it on someone."

A prison education

Although nobody was killed in the crime, Ndungu was initially given the death penalty – a sentence that was later converted to life imprisonment.

"I felt as if the world had come to a standstill," Ndungu said. "I was just 21, and now you have been told you have to go and wait for an appointment with a hangman. It was more than I could handle at that age."

But he pressed on. Encouraged by other inmates, the Bible and self-improvement books, he continued with his education.

In 2004, on the same day that Ndungu exhausted his last appeal, he enrolled in an accounting program at Kenya’s Strathmore University. He received a professional certification in 2010, and since then has pursued a bachelor’s degree.

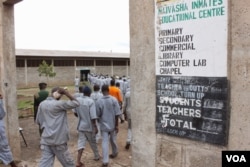

And he could not ask for a better prison than Naivasha, where more than half of its 3,000 inmates are involved in the institution’s education programs.

In a warehouse on the prison campus, in classrooms divided by corrugated steel walls, correction officers and prisoners teach primary and secondary level courses from English to physics, religious studies and math.

The principal is a former teacher serving a life sentence for murdering his girlfriend, although he says he didn’t do it.

Those less interested in schoolbooks can study metalworking or tailoring. One inmate teaches a course in portrait painting.

Despite this supportive atmosphere, Ndungu said the stress of his conviction was wearing him down.

"You don’t know what the future holds. You don’t know whether you’ll go home or do what, so stress is consuming and it affects my education," he said.

Hopes pinned on a pardon

His only hope for freedom was the Power of Mercy Committee, an advisory board formed in 2011 to review prisoners’ cases and, if deemed appropriate, to recommend a presidential pardon.

Mwenda, Naivasha’s officer in charge, said if Ndungu had not escaped, he would have pressed his case to the committee.

"In fact, I was waiting for him to graduate, possibly early next year," Mwenda said. "It was a case we were very ready to present and really push it to ensure that he is released, but now there we are."

At least one prisoner from Naivasha has been released through the committee, while Mwenda helped arrange for eight others to have their sentences commuted to probation through the courts.

Even with that support, accessing the Power of Mercy Committee is not that easy.

According to a report from Kenya’s Daily Nation newspaper, the committee received more than 3,000 requests for pardons last year from Kenyan inmates, while only a handful will ever be pardoned.

The committee is supposed to meet six times a year, but public records of their activities are not available.

Power of Mercy Committee members declined to speak to VOA for this story.

Concerns about corruption

The high court lawyer, Rabala, said advocates are unfamiliar with the procedures for presenting a case. Having assisted on appeals to the committee, he said the process is laborious and opaque and noted concerns it, too, has been compromised by the usual scourge of corruption.

"We’ve gotten information that people part with money for people to be in the good books of the prison officers, who basically have the key," Rabala said. "If the warden says that you have been of bad behavior inside there, basically you are done."

An attorney for the Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission, in a 2010 presentation, cited evidence of bribery and other corruption in the judiciary system. The suspensions of four senior Kenyan judiciary figures last year and allegations of misconduct elsewhere have eroded public confidence in the country’s legal system, the Institute for War and Peace reported.

Transparency International, a corruption-fighting nonprofit organization, last year ranked police as Kenya’s most corrupt institution. The judiciary system ranked slightly better, at third.

Another frustrated inmate

Another educated inmate at Naivasha, Prince Winsor Mosii, also expressed disappointment in the system during an interview with VOA in October.

Like Ndungu, Mosii is serving a life sentence for armed robbery. He teaches English, biology and agriculture and took his secondary school exams in 2013, but he had a feeling all his work was leading nowhere.

"The problem is that the Power of Mercy is not actually helpful," he said. "It is there, but it is not helping in setting us at liberty, even if you have performed."

Facing these extreme odds, Peter Ndungu must have decided he would rather risk spending his life as a fugitive than to fight for a pardon in a justice system that he believed had let him down for the past 16 years.

As he watched time tick by and opportunities slip away, it was clear he thought he deserved a better life than the one offered behind bars.

"I don’t think there’s any prisoner in Kenya who has struggled with education the way I have," he told VOA months ago. "I think I have done enough."