The young doctor sweats in the barren parking lot of Zithulele Hospital, in Oliver Tambo District in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province. But it’s not just a searing midday sun that’s responsible for the rivulets of perspiration running down his cheeks.

Dr. Thembinkosi Motlhabane is waiting anxiously for an ambulance to rush one of his critically ill HIV-infected patients to a bigger medical facility in Mthatha, a city more than 60 miles away. The doctor’s worried that the man’s body is collapsing.

Zithulele, an isolated rural hospital in one of the poorest parts of South Africa, doesn’t have an intensive care unit to provide the patient with the urgent attention he needs to stay alive. It doesn’t even have an ambulance.

“You are faced with someone who is dying, and you know that if he’s transported somewhere with better facilities, he’ll be saved,” said Motlhabane. “But the ambulance has to come all the way from Mthatha. If it’s still busy with another hospital then you have to wait…sometimes 12 hours. Sometimes it doesn’t even come.”

His colleague, Dr. Liz Gatley, said it often takes days for an ambulance to collect seriously ill patients. “Then, when the ambulance comes, it rarely has paramedics, because there’s a huge shortage of paramedics here,” she said.

Because of circumstances like these, people whose lives should have been saved sometimes die, acknowledged Ben Gaunt, the hospital’s head doctor.

Yet Zithulele isn’t one of South Africa’s typically dilapidated and severely under-funded public health facilities. It was recently almost completely refurbished. It has a full staff complement. Its health workers are leaders in the field of rural medicine.

But it’s also plagued by some of the same crises that have led international healthcare monitoring groups to consistently rate South Africa’s public health sector among the worst in the world. This, despite the fact that the government gives more than 100 billion rand ($13.3 billion) every year to state health – one of the biggest expenditures on such services in the developing world.

“It’s the poor who live far from the cities who are dying. The wealthier people can afford good private healthcare,” said Ncedisa Paul, a local community health worker.

Eighty percent of South Africa’s population of about 50 million people depends on public healthcare.

Gatley, provincial winner of South Africa’s Rural Doctor of the Year 2011 award, said the crisis is particularly evident in countryside regions like Oliver Tambo District.

“(Our) patients struggle to access care, so they often only get to us when they are very, very sick,” she pointed out. “I know it sounds like a silly thing to say but when doctors who come from other parts of the country come here, they comment to us on how sick our patients really are.”

The HIV and AIDS ‘drain’

Laura Grobicki is a South African physiotherapist who recently returned to her home country to work in rural health after working in Australia for several years. “What shocked me when I came back was the high rate of HIV. Most of the patients I see are infected. Most of my colleagues in Australia have never seen a patient with HIV,” she said.

Grobicki attributed the “sad state” of public healthcare in South Africa largely to HIV. “That’s putting a huge drain on our system, because of the total number of patients and how sick they are,” she said.

South Africa has more HIV-infected people than any other country – an estimated 5.5 million people. The state is providing life-saving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to more than a million of them. But many more aren’t getting the medicine they need to boost their weak immune systems. So they’re becoming extremely ill with infectious diseases.

“This, together with all the resources needed to roll out ARVs, is a massive burden for any country, let alone a developing country, to bear,” said Gaunt.

Major killers: TB and diarrhea

Tuberculosis rates are also “through the roof” in rural South Africa, said Gatley, especially because the disease is fueled by HIV. People with weaker immune systems are much more susceptible to TB.

According to the World Health Organization, South Africa accounts for about 24 percent of global HIV/TB cases. Studies show that six out of every 10 people with TB in the country are also infected with HIV.

Thembeka Gaushe, a senior nurse in Zithulele Hospital’s TB section, said overcrowding is a major driver of the sickness in South Africa’s rural regions.

“People in these areas are very poor and so they are forced to all live together in a single hut. TB is an airborne disease, so it spreads very easily in crowded conditions,” she explained.

Gaushe added that many rural patients stop taking their TB treatment and don’t test their children for infection, simply because they live so far away from medical facilities and can’t afford transport.

In Oliver Tambo District, the TB rate is exacerbated by a high rate of silicosis – a respiratory illness that destroys lungs and is often contracted by miners who breathe in silica dust. Many men in the region work, or once worked, in gold mines in the northern parts of South Africa.

Ncedisa Paul said many children in the countryside are killed by diseases that are easily treated in more resource-rich areas – again because of the great distances involved in accessing healthcare, and lack of clean water.

“Babies die a lot, from diarrhea especially,” said Paul. District resident Nosintu Sali added, “There are no taps around here. People are fetching water from the river. They just go and fetch and drink, without boiling the water.”

No medicines; administrative chaos

Disease rates, as well as numbers of deaths, spike when rural public healthcare facilities run out of medicines and other essentials and the government fails to deliver important medical equipment.

“We’ve run out of TB treatment; we’ve run out of antibiotics,” said Gatley. “It’s happened that we were down to one or two IV (intravenous) antibiotics, which is ridiculous.”

She said hospitals and clinics endure regular shortages of the “most basic” of medical apparatus. “We’ve run out of surgical gloves. We’ve run out of oxygen many times before… Sometimes it means people die.”

Gatley said public health workers order basic supplies from the government, but they never arrive. “So now we buy all our stationery ourselves, like printing paper, which we need for data sheets, and our whiteboard markers and so on,” said Shannon Morgan, an occupational therapist at Zithulele hospital. “I run a department on donations and self-bought materials. We use our own cars and petrol to visit patients who are too disabled to come here.”

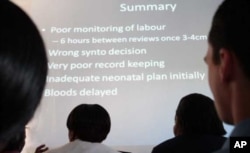

Health workers claim South Africa’s public healthcare system, especially in the more isolated districts, is characterized by bad management, administrative inefficiency and poor planning.

Rural health specialist Dr. Ben Gaunt said many shortages of essential material were because of “bad administration.” The manager of another state rural hospital, who asked not to be named, was more scathing in her criticism.

She said, “Procurement and budgeting and human resources – all of those support services – are sometimes a shambles. It’s disastrous. You have people in hospital management who just don’t know the first thing about their job.”

Gaunt added, “It’s true that there are (state) departments in parts of the country where the health support staff are just downright obstructionist at times. I don’t get that feeling here (in the Eastern Cape) but there’s not perhaps as much competence as there could be.”

Gatley commented, “(In the public sector) there are quite a few people working excessively hard to try and get things done, and there are a lot of other people who just don’t do their jobs and there’s no recourse and no evaluating of that, and I think that creates resentment and frustration.”

Gaunt said rural public healthcare in South Africa is now suffering “tremendously” because of incorrect management and administrative appointments made in the past. “It’s not necessarily because people don’t want to do their jobs. They just sometimes don’t know how to,” he commented.

Critical doctor shortage

South Africa’s health department has acknowledged that rural public health facilities are facing a shortfall of thousands of doctors. Some state hospitals and clinics in the countryside don’t have a single doctor.

Mainly because of “terrible” working conditions in the state health sector, said Gaunt, doctors have in recent years left it “in droves” – either for the well managed private health sector or to work overseas in developed countries, where labor conditions are superior and salaries much higher.

According to the South African Medical Association, 70 percent of the country’s doctors work in private care.

A major reason for the “doctor void” in public health is that state physicians “burn out,” said Gatley. “In many public facilities people are really, really stretched. They’re exhausted, because you’re doing a lot of work without the resources that you need to do that job, which is immensely frustrating, and also with too few staff.”

Grobicki said that another factor is “all the death and suffering” caused by HIV and TB that’s “taking an immense toll on South African health workers. Compassion fatigue is a huge part of public service.”

The South African National HIV Survey has estimated that there’s an average of almost 1,000 AIDS deaths a day in South Africa.

“Working with so many patients who don’t make it, and the accompanying sadness and depression, causes many people to walk away from public health in South Africa,” said Grobicki.

Gatley acknowledged, “I have cried – many, many times – at work. I have felt close to burn-out at times, and I think a lot of people here have as well.”

Nurses leave

South African state nurses are also abandoning the public health sector.

“I’m too old now to leave,” said senior nurse Thembeka Gaushe. “But for many of my younger colleagues, it is their dream to be employed in private health.”

She explained that nurses commonly cite “horrible” working conditions and “stress from seeing patients suffer non-stop” as primary reasons for leaving the state sector.

“My TB patients don’t even have a toilet. The toilet is outside. When they go out there on rainy days, they become wet. Even the doors, they don’t close properly in that toilet,” said Gaushe, adding, “When we are taking disabled patients to the toilet, pushing the wheelchair around here is difficult because there are no proper pavements. We have to carry the patients up the steps, and that’s very difficult.”

She said many rural public hospitals in South Africa don’t have adequate facilities to clean feces from linen. “We should have a sluice room to do this, so that all the feces is washed from linen before it gets to the proper washroom. So what happens is linen is not properly washed and that’s very bad for everyone, it’s a big health risk for us all.”

Gaushe said, “I’d like to know how many other people are willing to work in conditions like this every day without getting angry and uncaring.”

Zithulele Hospital, she said, like other rural hospitals in the country, lacks a facility to temporarily store corpses when porters aren’t available to transport bodies to morgues. Gaushe said patients thus lie with corpses for “many hours.”

“Can you imagine that?” she asked. “These people are so sick themselves and so scared of death themselves, and now they have to stare at a dead body for the whole night. It terrifies them, but all we can do is to cover the body and wait….”

South Africa’s health minister, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, has won praise for acknowledging the chaotic state of the public health sector and pledging to do his best to remedy the situation.

But for Gaushe and many other health workers, and for the patients who continue to suffer and even die, the reforms so far instituted by the minister aren’t enough. And the public health sector in Africa’s biggest economy, and especially in its rural hinterland, continues to lurch from crisis to crisis.