As news of the death by a drone strike of Afghan Taliban leader Mullah Akhtar Mansoor emerged, the usual Taliban spokesmen accessible to media disappeared. So far, there has been radio silence from official Afghan Taliban sources.

Behind the scenes though, it is probably quite different. Hectic messages are likely going back and forth among senior Taliban leaders.

The Taliban have a structure for situations like these, according to Nazar Mohammad Mutmayeen, a pro-Taliban analyst based in Kabul.

Council

The first thing they do when their leader is killed is call a meeting of their Rahbari Shura, or leadership council.

"They would like to hold that meeting as soon as possible," according to Rustam Shah Mohmand, Pakistan's former ambassador to Afghanistan. "They would like to send a message to the world that they are united and will continue with their war."

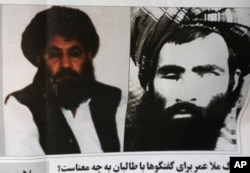

In a similar situation in July 2015, when news emerged that Taliban leader Mullah Mohammad Omar had been dead for at least two years, the shura met and decided on the successor within a few days.

That situation, however, was much different.

Mansoor, the successor to Mullah Omar, had been a deputy to him and one of the founding members of the Afghan Taliban. Yet he still faced serious challenges to his leadership from within the group, including from Omar's brother and son.

Analysts said one of the reasons that Mansoor ratcheted up the level of violence in Afghanistan was to overcome those challenges. He needed to prove his loyalty to the movement, prove himself as an able battlefield commander and overcome a reputation of being Pakistan's puppet.

The current succession debate may be more divisive.

"Afghanistan is a tribal society," according to Mohmand. "Agreement on a single leader is not always easy."

Compromise

This is why Mohmand thinks the shura would place the utmost emphasis on trying to keep the movement together, even if it has to come up with a compromise candidate who lacks the stature of Omar, or even Mansoor.

The security challenges involved for top Taliban commanders to travel means that all of the shura members may not be able to gather in one place.

The Taliban rulebook states that in situations like these, whichever shura members were present in or around Quetta or Kandahar would meet to decide on an interim leader, until a permanent one was elected.

If it looked difficult for the entire shura to gather within a reasonable time, the smaller group might decide on a candidate who could then be presented to other members for endorsement.

An announcement by the shura, however, is by no means a guarantee against infighting. When the Taliban announced Mansoor's leadership, three current or former members of the shura openly disagreed with the decision.

Violence

While Afghanistan might get a reprieve from larger attacks during this time, small-scale operations in various Afghan provinces would likely continue.

The Taliban have a shadow governor and a commander in each of Afghanistan's 34 provinces who are quite independent when it comes to local operations, according to Nazar Mohammad Mutmaeen, a pro-Taliban analyst based in Kabul.

"For the small operations, they don't need approval," he said.

He also said that the Taliban shadow governors were quite cooperative toward each other.

When the Taliban in Nangarhar needed help, for example, the Taliban in Ghazni went to Nangarhar, he said. Similarly, when they needed help in Kunduz, the Taliban came from all over the north.

"The real question is what will happen to the morale of the Afghan Taliban on the ground," Mohmand said.

If the fight for succession becomes prolonged, however, it could spill onto the battleground.

A similar episode happened after Mansoor's succession, between him and his rival, Mullah Muhammad Rasool. The two had to literally fight it out on the battlefield before Mansoor managed to mostly sideline Rasool.