Scientists are more certain than ever that human activity is to blame for a warming climate and those findings are expected to be included in a report released this week from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world authority on the issue.

Climate experts and government officials are meeting in Stockholm this week to finalize the report.

What the IPCC report illustrates is the important role science plays in decision-making, says K. John Holmes, an energy analyst with the National Research Council, who believes history holds scientific lessons for policy makers.

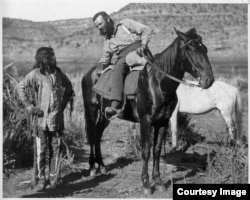

Writing in Nature, the energy analyst with the National Research Council singles out legendary 19th century geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell, who is celebrated for promoting sustainable development across desert lands in the American West.

“He really introduced this idea of integrated assessment of large-scale environmental issues,” Holmes said.

Powell’s plan called for detailed scientific surveys. It outlined initiatives to develop water, land and mineral resources. Holmes says as settlers moved west, those ideas were met with intense political debate over access to natural resources and adaptation to climate.

“Powell, even though his plan was never implemented, his assessment provided what the USGS [United States Geological Survey] called ‘definitive information upon which the committees of Congress and individuals interested could base their statements or conclusions.’”

But the data did not end the debate. Laws to allocate resources took decades to enact. Holmes says Powell’s legacy reminds us of the central role science plays in decision-making, reflected today in reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“It brings that fundamental set of facts and common knowledge that can be used by global governments everywhere to bring the science to the debate,” Holmes said.

Those views are shared by Elliot Diringer, with the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, a bipartisan research group.

“I think the IPCC assessments are a critical opportunity to focus global attention of the reality of the problem and the urgency of addressing it,” he said.

Diringer says addressing climate change has played out on the world stage under the global warming treaty known as the Kyoto Protocol. When it expired in 2012, negotiators agreed to replace it with a new treaty by 2015. Diringer says what is emerging is a more workable, inclusive approach.

“This is something perhaps not as rigorous as the Kyoto Protocol, but more rigorous than what may have appeared to be the alternative, which is a strictly voluntary bottom up approach," Diringer said. "In Kyoto, you had binding targets for developed countries only. No new commitments for developing countries. That is not going to fly this time. All the major economies are going to be expected to step up and prepare to take action.”

Diringer says countries would design their own commitments apart from negotiations, while at the same time commit to monitoring, periodic reporting and international scrutiny on those self-imposed commitments.

“Basically what you need is institutionalized peer pressure.”

As climate negotiations continue, side accords are being worked out. Ninety nations stepped forward in 2009 with voluntary pledges to reduce emissions, including for the first time all the world’s major economies. While the countries represent 80 percent of global warming emissions, their actual pledges fall short of the level needed to limit global warming.

What they do provide, Diringer says, is a fresh start on a comprehensive treaty.

“Hopefully, what we will have created is a more durable framework that can help to elevate the level of ambition over time,” Diringer said.

Writing in the journal Nature, Diringer says a new agreement forged from this patchwork of national efforts “can strengthen countries’ confidence in one another, in the process and in our collective ability to overcome the climate challenge.”

Climate experts and government officials are meeting in Stockholm this week to finalize the report.

What the IPCC report illustrates is the important role science plays in decision-making, says K. John Holmes, an energy analyst with the National Research Council, who believes history holds scientific lessons for policy makers.

Writing in Nature, the energy analyst with the National Research Council singles out legendary 19th century geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell, who is celebrated for promoting sustainable development across desert lands in the American West.

“He really introduced this idea of integrated assessment of large-scale environmental issues,” Holmes said.

Powell’s plan called for detailed scientific surveys. It outlined initiatives to develop water, land and mineral resources. Holmes says as settlers moved west, those ideas were met with intense political debate over access to natural resources and adaptation to climate.

“Powell, even though his plan was never implemented, his assessment provided what the USGS [United States Geological Survey] called ‘definitive information upon which the committees of Congress and individuals interested could base their statements or conclusions.’”

But the data did not end the debate. Laws to allocate resources took decades to enact. Holmes says Powell’s legacy reminds us of the central role science plays in decision-making, reflected today in reports issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“It brings that fundamental set of facts and common knowledge that can be used by global governments everywhere to bring the science to the debate,” Holmes said.

Those views are shared by Elliot Diringer, with the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, a bipartisan research group.

“I think the IPCC assessments are a critical opportunity to focus global attention of the reality of the problem and the urgency of addressing it,” he said.

Diringer says addressing climate change has played out on the world stage under the global warming treaty known as the Kyoto Protocol. When it expired in 2012, negotiators agreed to replace it with a new treaty by 2015. Diringer says what is emerging is a more workable, inclusive approach.

“This is something perhaps not as rigorous as the Kyoto Protocol, but more rigorous than what may have appeared to be the alternative, which is a strictly voluntary bottom up approach," Diringer said. "In Kyoto, you had binding targets for developed countries only. No new commitments for developing countries. That is not going to fly this time. All the major economies are going to be expected to step up and prepare to take action.”

Diringer says countries would design their own commitments apart from negotiations, while at the same time commit to monitoring, periodic reporting and international scrutiny on those self-imposed commitments.

“Basically what you need is institutionalized peer pressure.”

As climate negotiations continue, side accords are being worked out. Ninety nations stepped forward in 2009 with voluntary pledges to reduce emissions, including for the first time all the world’s major economies. While the countries represent 80 percent of global warming emissions, their actual pledges fall short of the level needed to limit global warming.

What they do provide, Diringer says, is a fresh start on a comprehensive treaty.

“Hopefully, what we will have created is a more durable framework that can help to elevate the level of ambition over time,” Diringer said.

Writing in the journal Nature, Diringer says a new agreement forged from this patchwork of national efforts “can strengthen countries’ confidence in one another, in the process and in our collective ability to overcome the climate challenge.”