Helping Africa produce more and better crops to reduce hunger and poverty and create long-term employment security – that’s today’s U.S. approach to aiding African farmers. It replaces the former policy of working toward shorter term humanitarian goals.

The food crisis is continuing in many African countries, with prices much higher than normal. But this is also an opportunity for the continent, according to the director for Africa at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in Washington, Ousmane Badiane. He gives two reasons:

“The first one is that the crisis originated from outside of Africa and it had not permeated African economies the way it has affected the global market.”

The second, he says, is that agriculture for export in Africa is a problem only if it affects the supply base. If it has the base, the food to sell, it can benefit from the higher prices.

A trade-off

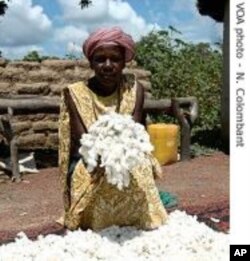

The Africa food specialist says farmers may be paying higher prices for maize to consume, but they are also getting higher prices for cotton, which off-sets the cost of the maize.

He says the higher prices for exported food are an opportunity for farmers, but the economic crisis can also hurt them because it affects available income outside of Africa, and if buyers have less income, demand falls and prices fall.

Also affected by these crises are people who work in agri-business, which processes and distributes Africa’s goods. Badiane says one of their concerns is a lack of credit. The economic crisis has made it difficult for banks around the world to lend money, including banks in Africa.

“So what you then do for the agri-business sector,” Badiane says, “is first of all look at where they’re being hurt the most – and credit has got to be a part of it – and see, if you have the money, how you can lower the cost of access to credit for them.”

The principles that apply to farmers also apply to agribusiness, says Badiane. If agribusiness processes and exports food, he says, they will make more money.

Go for it

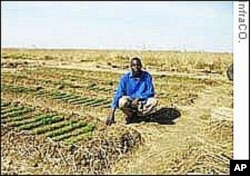

The best short-term goal for farmers, says Badiane, is to grow as much food as possible.

“Africa has a lot of catching up to do in terms of growing and reducing poverty, and the main sector that can get them out of poverty over the next two decades or so, is agriculture.”

Africa’s exports, he says, have grown faster than the exports of the rest of the world, so Africa is in a better position to compete, and governments should capitalize on that.

The “little guy”

It’s especially important to invest in Africa’s small-scale farming sector, says Badiane, so it can benefit from higher prices. He adds the best ways to do this are not to give in to what he calls the hysteria surrounding these problems and not to interfere with the good reforms of the past that have put agriculture back on the path of growth.

“Avoid interfering with the private sector, avoid interfering with the banking sector, avoid interfering with the choice(s) and the opportunities of the smallholders to go where the opportunities lead them.”

The main concern now, says Badiane, is making wise investment decisions that can stimulate a return to a healthy economic situation for agriculture, rather than focusing on helping individual farmers.

The economic crisis, he says, directly affects the food crisis in three ways:

Less money is available in government budgets to stimulate private investment that would give farmers more opportunities to benefit from higher prices for their crops.

Less credit is available for agribusiness and others to be able to sell their products on the world market.

Less world demand for agricultural goods means a drop in Africa’s earnings.

Despite these problems, Badiane sees the importance of exporting as much as possible in order to take advantage of higher prices for agricultural goods.