A new U.N. report for the first time puts Myanmar’s armed forces on a U.N. blacklist of government and rebel groups “credibly suspected” of carrying out rapes and other acts of sexual violence in conflict.

An advance copy of Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ report to the Security Council, obtained Friday by The Associated Press, says international medical staff and others in Bangladesh have documented that many of the almost 700,000 Rohingya Muslims who fled from Myanmar “bear the physical and psychological scars of brutal sexual assault.”

The U.N. chief said the assaults were allegedly perpetrated by the Myanmar Armed Forces, known as the Tatmadaw, “at times acting in concert with local militias, in the course of military ‘clearance’ operations in October 2016 and August 2017.”

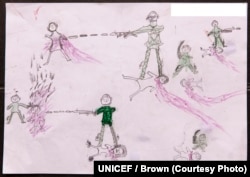

“The widespread threat and use of sexual violence was integral to this strategy, serving to humiliate, terrorize and collectively punish the Rohingya community, as a calculated tool to force them to flee their homelands and prevent their return,” Guterres said.

Buddhist-majority Myanmar doesn’t recognize the Rohingya as an ethnic group, insisting they are Bengali migrants from Bangladesh living illegally in the country. It has denied them citizenship, leaving them stateless.

Recent wave of violence

The recent spasm of violence began when Rohingya insurgents launched a series of attacks last Aug. 25 on about 30 security outposts and other targets. Myanmar security forces then began a scorched-earth campaign against Rohingya villages that the U.N. and human rights groups have called a campaign of ethnic cleansing.

“Violence was visited upon women, including pregnant women, who are seen as custodians and propagators of ethnic identity, as well as on young children, who represent the future of the group,” Guterres said. “This can be linked to an inflammatory narrative alleging that high fertility rates among the Rohingya represent an existential threat to the majority population.”

Governments and extremists

The report, which will be a focus of a U.N. Security Council meeting Monday on preventing sexual violence in conflict, puts 51 government, rebel and extremist groups on the list.

They include 17 from Congo including the armed forces and national police, seven from Syria including the armed forces and intelligence services, six each from Central African Republic and South Sudan, five from Mali, four from Somalia, three from Sudan, one each from Iraq and Myanmar, and Boko Haram which operates in several countries.

“As a general trend,” Guterres said, “the rise or resurgence of conflict and violent extremism, with its ensuing proliferation of arms, mass displacement, and collapsed rule of law, triggers patterns of sexual violence.”

This was evident in many places in 2017 as insecurity spread to new regions in Central African Republic, violence surged in eastern and central Congo, conflict engulfed South Sudan, violence wracked Syria and Yemen, and “ethnic cleansing in the guise of clearance operations unfolded in Northern Rakhine State, Myanmar,” he said.

Guterres said most victims are “politically and economically marginalized women and girls” concentrated in remote, rural areas with the least access to services that can help them, and in refugee camps and areas for the displaced.

The year 2017 “also saw sexual violence continue to be employed as a tactic of war, terrorism, torture and repression,” he said, citing conflicts in CAR, Congo, Iraq, Mali, Myanmar, Nigeria, Somalia and South Sudan as examples of “this alarming trend.”

Guterres said sexual violence continues to serve as a “push factor” for forced displacement in places such as Colombia, Iraq, the Horn of Africa and Syria. And he said it remained “a heightened risk in transit, refugee and displacement settings.”

Impact lasts generations

The secretary-general said the effects of sexual violence can impact generations as a result of trauma, stigma, poverty, poor health and unwanted pregnancy.

In South Sudan, for instance, Guterres said sexual violence is so prevalent that a Commission of Inquiry described women and girls as “collectively traumatized.” He said children born of this violence have been labeled “bad blood” or “children of the enemy” and warned that this vulnerability “may leave them susceptible to recruitment, radicalization and trafficking.”

Guterres said many women, including Rohingya refugees, are reluctant to return to locations they fled where forces including alleged perpetrators remain in control.

“Colombia is the only country in which children conceived through wartime rape are legally recognized as victims, though it has been difficult for them to access redress without being stigmatized,” he said.

The secretary-general lamented that “most incidents of mass rape continue to be met with mass impunity.”

For example, Guterres said, not a single member of the Islamic State extremist group or Boko Haram “has been prosecuted for sexual violence offenses to date.”