French far-right leader Marine Le Pen's plan to change the National Front's name amounts to political suicide, its founder, her father Jean-Marie Le Pen told Reuters, warning that his daughter was cutting herself off from the party's roots.

Le Pen father and daughter have been at odds since she kicked him out of the party in 2015 in a bid to distance herself from his frequent inflammatory remarks, which put off a large part of the electorate.

Now she wants to go a step further and rebrand the 45-year-old party after she lost the presidential election last year to centrist Emmanuel Macron.

At a congress mid-March she will ask cardholders to agree to drop the National Front's name, a trademark well known in France and abroad but which party insiders say puts off potential voters and is an obstacle to alliances with other groups.

“This initiative is suicidal. That would be so for a company, and that is obviously also the case in politics,” the 89-year old far-right veteran, who has been involved in French politics for over 60 years and is still an EU lawmaker, said in an interview in his mansion on the outskirts of Paris.

“It takes years, decades, to build a credible political name. Wanting to change it is ... inexplicable,” he said.

Already a best seller

No names have been floated yet. Marine Le Pen said she would propose a name at the congress. All party members will be eligible to vote.

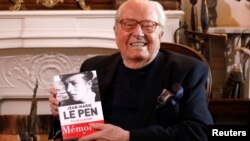

Jean-Marie Le Pen, who led the National Front (FN) for nearly four decades before passing on the leadership to his daughter in 2011, is publishing on Thursday the first volume of his memoirs, in which he writes that he pities his daughter for losing last year’s election to President Emmanuel Macron.

The memoirs, which can be pre-ordered online, are the top selling book on Amazon in France.

“Her failure comes from strategic and tactical errors ... from pushing the fight against immigration aside and focusing on the fight against the euro and Europe,” Le Pen senior said in the interview.

Although she lost last year’s election, Marine Le Pen’s efforts to clean up the party's image have paid off to some extent. She won a third of the vote in the run-off, almost double her father’s best showing in his 40 years at the party’s helm.

Jean-Marie Le Pen too made it once to the second round of the presidential election, but his surprise qualification for the run-off in 2002 triggered a huge backlash, and he won less than 18 percent of the vote.

Marine Le Pen watered down her anti-euro stance, which has proved unpopular beyond the party’s core fans, after the election, refocusing the party on migration and security as other far-right parties in Europe have done.

The March 10-11 congress in the northern France city of Lille is meant to back that change of focus and give her a new mandate at the helm of the party.

No regrets

While Jean-Marie Le Pen still has a loyal following among veteran party members, younger cardholders say they are more comfortable with his daughter's less provocative brand of politics.

His memoirs dwell mostly on the first part of his life, before the FN was set up.

He rejects allegations that he practiced torture while a French soldier in Algeria during the north African country’s independence war, but says that beatings and electric shocks were carried out by others and were necessary to obtain information.

His expulsion from the FN came after he reiterated past comments that World War Two gas chambers were a “detail” of history. He has also defended France's WWII leader Philippe Petain, who died in jail after being condemned for high treason for his collaboration with Nazi Germany.

Le Pen, who has been convicted several times for incitement to racial hatred, said in the interview that he had no regrets.

Describing himself as a whistleblower warning against immigration, he accused French judges of being politicised and said he stood by his remarks on Nazi gas chambers, for which he was also convicted.

“Why would I have any regret or any remorse when I’ve got nothing to be blamed for?” he said.