Rodeo is a uniquely American sport generally associated with “cowboys,” but some of its best riders are “Indians,” growing numbers of whom are women.

Horses disappeared from prehistoric North America more than 10,000 years ago, and didn't return until 1519, when the Spanish brought them to modern-day Mexico. Migrating north, they transformed the ways Native American tribes hunted, traded and conducted warfare.

“I like to think that Native Americans took the horse to a whole new level by riding horses bareback, without a saddle,” said Mike “Bo” Vacu, president of the Indian National Finals Rodeo (INFR) and a member of South Dakota’s Oglala Lakota tribe. “There was a oneness between the rider and the animal, and we mastered the horse in our culture.”

That special bond is still in evidence today, he said.

“Especially in rodeo. You see Native American cowboys praying with their animals before a ride, something you don’t see very often in the non-Native world.”

The word “rodeo” is derived from Spanish and means “to surround.” It originally referred to annual roundups of cattle on Western ranches, tough work that demanded special skills with horses and rope. "Competitiveness among cowboys was only natural,” said Vacu.

“Out of boredom or just being men,” he laughed. “Some cowboy on some ranch had a horse that couldn’t be broken to ride. Another ranch had a cowboy who thought he couldn’t be bucked off. And that’s when the competition began: Who’s the best rider? Who has the toughest bronc [untamed horse]?”

Battling discrimination

Informal competition led to more organized events, and the sport was formalized in the early decades of the 20th century, with timed, judged categories such as bull and bronc riding, barrel racing and steer wrestling.

But Native American riders weren’t easily accepted into the sport.

One early exception was Jackson Sundown of the Nez Perce tribe, said to have been so skilled at staying on a horse that other riders refused to compete with him. After many attempts, he finally won the World Bronc Horse Championship at the Pendleton (Oregon) Roundup in 1916.

“There were several times he didn’t get a win when maybe he should have, and when he finally did, there was no social media to share the word and change the hearts of every judge out there. It was a memorable event, but it didn’t do much for Indians as far as what became the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association.”

The INFR was organized in 1976 to give U.S. and Canadian Native cowboys and cowgirls of all ages an opportunity to compete in nearly 200 events a year, culminating in a finals competition held each November in Las Vegas, Nevada (see highlights video, below).

Not for the faint of heart

Women have always been a part of rodeo, but their participation in so-called “roughstock” riding – riding broncs and steers—is discouraged.

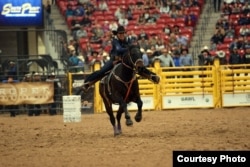

“The only two events that ladies enter are breakaway [calf] roping and the ladies barrel racing,” said Sammy Jo Bird, 25, a member of Montana’s Blackfeet Nation who won the title of World Champion All Around Cowgirl at the INFR finals last year after eight years of trying.

Her father Sam was a legendary rider, and several other family members have also made names for themselves in competition.

“It’s definitely a family-oriented event,” she said. “And the guys? They’re not sexist at all. They’d literally give you the shirts off their backs, and I would do the same for them.”

Rodeo is not for the faint of heart, she said, describing the formidable costs of owning horses and gear, and traveling long distances by truck and trailer to events. When VOA caught up on the phone with Bird, she had just made a 21-hour drive from Oklahoma and was about to head to South Dakota’s Rosebud Reservation for its annual fair and rodeo.

In spite of the hardship and the cost, Bird calls rodeo a “godsend.”

“Growing up on the Blackfeet reservation where there’s a lot of oppression and depression, it’s hard to stay on the right track, stay goal-oriented and not get caught up in all the trouble in terms of drugs and alcohol,” she said. “After winning the World Championship and getting some recognition, I really want to work to inspire the youth and show them that wherever you grow up, whatever your circumstances, they don’t determine where you can end up.”

Ultimately, she added, rodeo is so much more than just a sport.

“For us, it’s a way out.”