Student Union

Camel Driver to Law Student: One Man's Amazing Journey

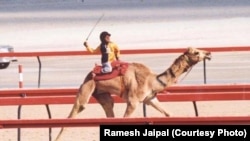

Desperate to feed their family, Ramesh Jaipal's parents sold him to a business in Dubai to help train and scrub camels for 10,000 Pakistani rupees a month.

He was 5.

"I deserved love, I deserved education and I deserved a family, but I was scrubbing camels and racing them in the scorching temperatures of 106 degrees (Fahrenheit/41 degrees Celsius)," Jaipal told VOA.

Because the United Nations was retrieving boys and girls like Jaipal from servitude and returning them home, he was able to go to school, but only up to the eighth grade.

Jaipal was also a rickshaw driver, a motor mechanic's assistant, a newspaper vendor, a shoe polisher and a car washer until he worked his way up the education ladder, receiving master's degrees in political science and sociology from Shah Abdul Latif University in Khairpur, Pakistan.

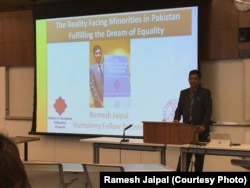

This year, Jaipal, 34, completed the most recent leg on his worldwide journey: as a fellow in the prestigious Hubert Humphrey Fellowship program to study law and human rights at American University's College of Law.

"I can never forget that I was once a camel jockey. … Today, I know for a fact that I am the only one among the thousands who would race for their lives like me, to make it to this point. Studying in America is a privilege, and only I have it among all of my fellow jockeys. It is an honor and it surely is a dream that is fulfilled."

The fellowship, administered by the U.S. Department of State, provides a $1,500 to $1,700 monthly stipend for study and living expenses.

"My family was dirt poor. I was the only son of my parents at the time, and I was hired on a salary of 10,000 Pakistani rupees [$200] a month," he recalled. "What more could my father ask for? He had to feed a family of four at the time."

Jaipal and his family are Dalit Hindus who lived in one of the poorest districts of Pakistan's predominately Muslim Punjab province, he told VOA in an interview at his apartment in Silver Spring, Maryland. For decades, southern Punjab has been a target for child trafficking.

According to reports, more than 3,000 children as young as 3 years old from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Sudan were smuggled to United Arab Emirates to serve as jockeys for the popular camel-racing sport in the oil-rich Gulf states. UNICEF and other nongovernmental organizations have returned many of these children to their families.

Jaipal says young children like himself were underfed and inadequately clothed, lacked strength and energy, and faced substantial health risks. That made them perfect for the job.

"I was fit for the job because I was physically unfit," he explained. "I was weak, and I was underweight, and I could make a camel run very fast. The sheikhs, who would train us, would not know Urdu, but they did know how to say 'maaro' or 'hit the camel' in my [native Urdu]. They would hit me to teach me so that I could hit the camel to make it run even faster."

When he was 8, he was forced to race an untrained camel in the desert. He suffered a head injury when the camel tried unsuccessfully to throw him off his back — an injury he still suffers from today. Despite his head trauma, Jaipal was forced to work a few more years. In 1995, when he was 11 years old, he was rescued by UNICEF and other child advocates.

Returned to parents who sold them

"Call it extreme poverty, lack of education or blame it on the system, but the truth is that most of the children who would go for this sport to UAE were actually sent there because the parents would sell them," said Sarim Burney, chairman of a trust that battles human trafficking in Pakistan. "And we would hand over these children to such parents upon their return."

No children are trafficked or smuggled from Pakistan to UAE for camel racing anymore, Burney says. But he remains concerned that several of the recovered children remain missing.

"I wish we could put a check on how these children were later treated by their parents," Burney said.

Jaipal says part of his life's mission will be to fight against child abuse in Pakistan today.

According to the 1998 Pakistani census, Jaipal's home district of Rahim Yar Khan has a population of 200,000 Meghwar people, also known as Dalits, or lower-caste Hindus. Jaipal says that the kidnapping and forced conversion of little Hindu girls to Islam has risen at an alarming rate in South Punjab and parts of Sindh.

"As a result, people have stopped sending their girls to school. … Here in America, I have learned how to lobby for a cause," he said.

Jaipal, with all his ambitions and dreams, is soon returning to his family in Pakistan.

"The exploitations and excesses I have faced in my country and by my family is my internal issue. I will keep fighting," he said.

"A day will come when the people of my community and of all the minorities of Pakistan won't have to face what I faced. My scars and wounds that I endured along the way will keep me remembering that I belong to Pakistan, which to me is the best place on Earth."

See all News Updates of the Day

- By VOA News

Michigan State international students get their own space

Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan, is setting aside a space in the International Center for international students.

Nidal Dajani, vice president of the school's International Student Association, said that the club plans to use the space to host events and hopes to collaborate with other student groups.

- By Dylan Ebs

International students find community during Pride Month

For LGBTQ+ international students, Pride Month, observed in June, is a unique time to reflect.

They hold on to multiple identities — both their LGBTQ+ identity and their cultural background — but coming to terms with them is not always easy.

For graduate student David Zhou, these identities can feel conflicting as transgender rights in China remain a controversial issue and spaces for LGBTQ people close. Zhou, 25, is transgender and pursuing an education in the STEM field at an urban university in the Midwestern United States.

VOA is using a pseudonym for Zhou’s first name and is not naming his university to protect his identity due to safety concerns back home in China. Zhou is not open about his transgender identity to his family.

During Pride Month, Zhou said he attended multiple LGBTQ+ events in his community and is surrounded by a supportive group of LGBTQ+ students who can relate to his experiences. But he’s not open about his identity to everyone on campus and said he doesn’t disclose his preferred pronouns to everyone to avoid transphobic comments.

“I feel like I have to make some judgments of the character of that person to see if they’re a good person to disclose [my identity] to,” Zhou said.

Zhou’s Pride Month celebrations included attending local markets with LGBTQ+ vendors and hanging out with his LGBTQ+ friends.

“They normalized being trans and for a long time I feel like trans identity is, should I say a vulnerability, brings me fear and worrying about discrimination, but having those events are helpful because it allowed me to see that queer people could just [live] openly,” he said.

At social events where few international students are present, Zhou said it can be tough to fit in.

“There's a lot of times like when they were talking about things I kind of, don't really understand, mostly because I kind of lack some background experience or knowledge,” he said.

Zhou said he is not aware of specific groups for LGBTQ+ international students at his university, but said international students are more prevalent in graduate programs and therefore find representation in organizations for LGBTQ+ graduate students.

In China, transgender individuals must obtain consent from an “immediate family member,” even for adults hoping to transition, which critics say limits the autonomy of transgender individuals while supporters say the policy protects doctors from violence by upset parents.

Struby Struble, a former coordinator of the University of Missouri LGBTQ+ Resource Center, told NAFSA: Association of International Educators in 2015 that LGBTQ+ international students face a “double barrier” on campus.

“With their international student friends, they feel isolated because they’re the LGBT one,” she said. “But then among the LGBT students on campus, they feel isolated because they’re the international one.”

Nick Martin, associate director of the Q Center, Binghamton University’s LGBTQ+ student support office, said when international students tour the center, there’s often a sense of hesitation as they enter a type of space that may not be present in their home country.

“I compare that to a year in after they've come into the space, they've again, maybe come to some of our events, they've got more connected,” he said.

Martin said graduate students have a unique interest in the Q Center as they may use the office for research and advocacy purposes that align with their studies.

“For older students, there may be hesitancy in a different way, but I think it's more in the vein of they want to do some of the advocacy work,” he said.

Martin said he thinks about how both his office and BU’s international student office can support students who come from countries with few — if any — protections for LGBTQ+ individuals.

“It's been a learning process of what those students really need, but I think I've kind of learned that a lot of students are just looking for the safe space that we offer,” Martin said.

- By VOA News

International students discuss US campus culture shock

International students at De Anza College in Cupertino, California, talked about culture shock in an article in La Voz News, the student newspaper.

"It felt like a major culture shock. Everything was so different, from academics to mannerism," said a student from Mexico.

Read the full story here.

These are the most expensive schools in the US

High tuition costs along with housing and food expenses can add up for students at U.S. colleges and universities.

MSNBC looked at the most expensive schools in the country, with one costing more than $500,000 for a bachelor’s degree. (June 2024)

Uzbekistan students admitted into top US universities

Students from Uzbekistan are among the international students admitted to top colleges and universities in recent years.

Gazata.uz profiled some of the Uzbekistan students attending Harvard, Brown, Princeton and other U.S. universities. (June 2024)