Alexa Olesen of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) covered China affairs as Associated Press' Beijing correspondent for eight years. Her latest piece, "Leaked Files Offer Many Clues to Offshore Dealings by Top Chinese," is part of the first series of ICIJ's Panama Papers. She tells VOA Mandarin service reporter Yinan Wang the leaked documents could provide insights about Chinese President Xi Jinping's domestically focused anti-corruption campaign.

VOA: What kind of organization is the International Consortium of International Journalists?

Olesen: ICIJ is based in Washington, D.C. It’s an independent organization that gets funding from places like the Ford Foundation, Open Society Foundation, some independent donors. It is a network of 200 investigative journalists who are based in more than 65 countries.

VOA: In countries like Russia and China, some people tend to believe that the documents leaked to ICIJ are really tactics by the U.S. to humiliate these two countries. What is your response to this opinion?

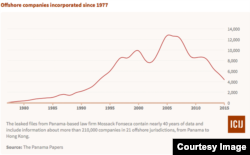

Olesen: In response to your question about the conspiracy theory, I think that came about because when the reports first started coming out, people noticed that there weren’t many American names being reported. But there’s a reason for that, which is that Mossack Fonseca [the law firm at the center of the Panama Papers case] itself has said they tend not to take American clients. So the company’s own business model is to focus more on Europe, Latin America, and also increasingly Asia.

So the reason why there weren’t many American customers to write about is because MF didn’t take that many. And of course, there’s no conspiracy. There was a news leak or a cache of documents that first came to the German paper Suddeutsche, and then they were shared with ICIJ, and we thought this information was of great public value to everyone. So that’s why we reported on that.

VOA: China’s state-backed Global Times ran an April 5 editorial accusing Western intelligence agencies of leaking the Panama Papers in order to target non-Western leaders such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, and to shore up Western ideologies. What is your reaction to these allegations?

Olesen: It's ridiculous, because if you look at the findings of our reports, you find it is actually very equitable. It’s embarrassing not just to Russia or China, it is embarrassing to the U.K., it's embarrassing to Iceland, it’s embarrassing to the United States. It’s embarrassing to many governments, individuals and politicians around the world. So to say this report is targeting Russia and China is not borne out by the facts.

VOA: Does ICIJ receive funds from the U.S. government?

Olesen: No, we don’t. Like I said, we are an independent organization. We get funding from groups like the Open Society Foundation, and also the Ford Foundation. There is a list of our supporters on our website. So if you want to go and look at that, it’s transparent to everybody where our funding comes from.

VOA: There were rumors saying ICIJ had invited a mainland Chinese publication as a partner in excavating the papers. Did ICIJ send out such invitation to Chinese media?

Olesen: The background on that is we did a similar project called “offshore leaks” in 2013. That dealt with much smaller leak of documents — offshore corporation documents. And we did have a mainland Chinese partner on that project in the beginning, and they had to drop out because the findings were too sensitive.

The second time around, when we started to work on this project ... we decided we didn’t want to put another Chinese publication in that position, where they would have materials either too sensitive to report on, or too sensitive to publish. So this time around, no, we did not have mainland Chinese partner.

VOA: Do you have the name of that Chinese publication?

Olesen: Yeah, I do. But we are not releasing that, because they didn’t want to be named.

VOA: Do you think Chinese authorities are afraid of document leaks disclosed by the Panama Papers?

Olesen: The fact that they have been censoring all of the revelations coming out of the Panama Papers does suggest that they are afraid of this information being made public. On Tuesday [April 5], at the Foreign Ministry press briefing, the Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei was asked about the revelation of the Panama Papers. He didn’t respond, or he said he had no comment. But even that question and that answer were deleted or not included in the transcript on the Foreign Ministry’s website. That’s one example. Also, they have been blocking out television broadcasts in China. When BBC queues up the Panama Papers, they just blocked it out. That suggests they are very nervous about it.

VOA: On April 7, one of the “red nobles” named in your report, Mr. Hu Dehua, son of the late general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Hu Yaobang, answered questions from a Hong Kong newspaper. Basically, he said that it is legitimate to register an offshore company. Do you think it is OK for these elites to establish offshore companies?

Olesen: There are many reasons why you would want to set up an offshore company. So in and of itself, it’s not a sign of anything illegal. But what we did in each of these cases that we reported on is we sent requests for confirmation, and also information to all the people we named, saying, "What is your company used for? Did you declare it to the Chinese authorities? Did you pay tax on whatever profit you earned from it?" So our question wasn’t, "Why did you do this legal thing?" but really, "What is your company used for? We found out you had it — what was the purpose?"

I am very glad that Hu Dehua has made some public comments about that company to help clarify. Ideally, everybody else in the article would do the same thing. In some cases, I think there’s nothing shady going on. But in other cases — for example, in the case of Gu Kailai, we know her company was set up to avoid taxes and so she could own a villa in the south of France. All these details came out when she and her husband went on trial.

VOA: Do you think the wealthy Chinese being named in the leaked Panama Papers will eventually become targets of China’s anti-corruption campaign?

Olesen: I would imagine that this database would be of great use to Wang Qishan [secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection] and other anti-corruption officials in China, that we gave them hints of people they should look at. If you are in the database, it doesn’t mean that you are automatically corrupt, but it does mean that you have some reason to want to have an offshore company. That’s something you would probably want to look into. ...

Li Xiaolin is an executive of a state-owned power company, and we found that she had a foundation in Liechtenstein. We wondered why she needed to have it. The documents told us that the company’s profit came from export business — heavy machinery export from Europe to China. So the question is: Does that income relate somehow to her job as a power executive, or is this another source of income that she hasn’t declared? We don’t know, but these are questions. And I think she should be required to answer them, because she is a public official.

This report was produced in collaboration with VOA's Mandarin service.