“Here’s a good first line for you,” says VOA photojournalist Yan Boechat as we drive up to a former ruling party office in Damascus.

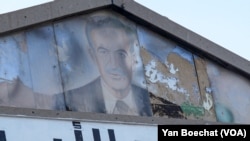

On the building are murals depicting Hafez al-Assad, the deceased dictator of Syria, and his son and successor, Bashar al-Assad, who fled Syria when the regime fell in December.

“The line is, ‘This may be one of the few places in Syria where pictures of Hafez are still intact,’” Boechat says.

And he is correct. Most of Syria’s public art of the Assads has been torn down or defaced. At the entrance to Damascus’ main market, posters of Bashar al-Assad’s face are placed on the ground for residents to stomp on.

But in this neighborhood, populated almost entirely by former regime soldiers and their families, the pictures remain untouched.

As we get out to take pictures, a young soldier on a motorcycle zips over. His hair is scruffy, and his face is covered with a green, polyester neck scarf.

He greats us politely, and my male colleagues shake his hand. The soldiers of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, also known as HTS, don’t shake women’s hands.

“It’s better if you coordinate with us,” the soldier says, after our translator explains that we are journalists, reporting on post-regime Syria.

“It’s over,” says Boechat, half sighing and half laughing.

He doesn’t mean a definitive end to the new days of a free press in Syria. But it’s certainly the end of locals in this neighborhood speaking openly. They are former regime fighters, and the new bosses are former rebels.

“Every day it’s a little more,” I joke when we get in the car to follow the soldier to his base.

When we first arrived in Syria in December, there were no regulations for the press, or really anything. Rebels had taken over Syria only days before. They hadn’t had time to set rules.

But on this trip, this was starting to change. We had to apply for entry and stop by the Ministry of Information for reporting permits. And now, soldiers on the streets were asking questions.

Of course, it’s still more free than under the Assads. If the regime was still in charge, we could have been arrested for reporting on our own.

During Bashar al-Assad’s rule, I applied for journalism visas — unsuccessfully — multiple times. A friend of a friend in the old Ministry of Information later told me my applications never reached them. The embassy officers would “file it to the trash,” like those of other unwanted Western reporters, we assumed.

As we arrive with the young soldier at his base — a low, single room shack by the roadside — our translator, Husam Yunso, speaks to the soldiers.

They tell us to ignore the locals in the neighborhood and delete the videos of them.

“They are regime supporters and liars,” one soldier says.

They offer us a tour.

We know that no one will speak openly when we are accompanied by armed guards, but they seem to be genuinely trying to help.

“It’s becoming more like Turkey,” Yunso says when we are back in the car.

Like in Turkey, Yunso points out, the security forces interrupted our work but didn’t threaten us.

“Let’s hope it stays at the level of Turkey,” Yunso says.

After the fall

The days after the regime fell were a free-for-all. In city squares, flags waved and music blasted. Elated rebels fired AK47s into the air.

As fighters freed thousands of prisoners, families crowded inside the emptied facilities, searching for clues about their missing loved ones. Journalists flocked to Syria’s borders.

Boechat, Yunso and I first crossed a few days later in a small bus packed with our equipment, a Syrian family and bags of bananas.

At an abandoned border-crossing station on the Syrian side, an HTS soldier, dressed in well-worn fatigues, poked his head into the window.

“Do you have any explosives?” he asked, before dissolving into laughter and waving us through.

On the road to Damascus, we saw abandoned military vehicles, their contents, including regime uniforms, scattered. An explosion near one such scene unnerved me. It turned out to be on the site of an already bombed weapons depot, courtesy of Israel. Presumably, some explosives were popping off from the fire.

On the way, Boechat regaled us with tales of the regime days, when journalists were assigned a “minder.” The minder could help secure interviews or translate, but their main job was to report back to the government about what the journalists were doing. Minders also served as a constant reminder not to touch taboo subjects.

A week later and still minder-free, we entered Sednaya Prison, the flagship house of torture for political prisoners under the Assad regime. It may not have been the worst in the country, but it was the most notorious.

Thousands of prisoners were freed from it when the rebels took over. Many left physically battered and mentally devastated, described by one former prisoner, named only as Ahmed, as “mummies, not people.”

Much of the trauma, Ahmed told us, came from witnessing nonstop deadly beatings and executions. When asked if he thought the families searching for lost relatives would find them, he replied, “There is no one. … They were all killed.”

Establishing order

By the time we returned to Syria in early January, the new Ministry of Information was up and running. Housed in the same building, it even had some of the same staff.

Nabih Bulos, the Middle East chief for the Los Angeles Times, greeted one such worker, and the men embraced.

“I never forget a face,” said Bulos, who worked in Syria multiple times under the old guard.

In the offices, there was some confusion, but no more than usual when trying to get permits for reporting. We finally left with a promise that a general permit would be sent via WhatsApp. We neither received that document, nor were we asked to present it.

A week later, the Ministry of Information sent an online form for journalists, asking them to detail work plans before they arrive. Like most new governmental institutions in Syria, press officials were still establishing their systems. It’s not yet clear how free the press will be to report.

So far, there has been no indication that journalists will be watched 24 hours a day, persecuted and sometimes even disappeared or killed, as was done under Assad rule. But the fear of oppression is present.

“We have nothing to be scared of anymore,” says one market seller, when we ask for an on-camera interview. His friends, two men leaning against the building and smoking, laugh and agree. “But yet, we are afraid to talk to the media.”

Late last week, as I left Syria, I found rows of cars waiting on the Syrian side of the border at around 6 a.m. The new leadership had manned the stations near the entrance to Lebanon.

“Under the regime, this was much faster,” says the taxi driver, while we wait to cross. “These guys are too slow.”

Boechat remained in Damascus to spend a few more days reporting. Among other things, there was that tour of the neighborhood where former regime soldiers live. But the young soldier never answered our calls or texts, so Boechat went as before, without a guide.

In the neighborhood, he took pictures again of the old Baath Party building. But now, the paintings of the Assads had been blacked out or removed.

Boechat met another HTS soldier, Omar, a thin, bearded man in a camouflage sun hat who spoke about the history of violence between the neighborhood and rebel groups. It was clear from his speech that not all was forgiven.

“There was a warehouse here where they used to take detainees … and torture them to death,” he said in an on-camera interview.

After leaving the area, Boechat headed up to a mountain that under the regime had been off limits to journalists and most other people. Near a checkpoint, he found families having tea on the grass. A white and gold Islamic flag was perched in the barrel of a large Soviet machine gun mounted on the back of a pickup truck.

Boechat lifted his camera and asked if he could shoot. “Sure, no problem,” said a soldier, posing with his fingers in a victory sign.

A nearby radio cackled, and a commander swept over to Boechat, telling him to delete the picture. Boechat said that he would do it later, but the commander wanted to see it happen on the spot.

“You cannot have that picture,” he said. “Delete it.”