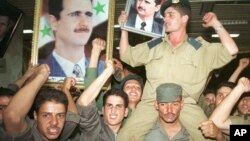

For more than a year, Syria experts have been predicting the imminent fall of the 42-year-old Assad regime, but President Bashar al-Assad continues to hold power and shows no sign of giving it up.

Even as rebel forces have moved into the suburbs of Damascus and are trying to close in on the capital’s center, some experts on the civil war say it could drag on for another four years.

“I don’t look at this conflict in terms of ending in 2013,” said Aram Nerguizian, a Syria expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington D.C. research organization. “I look at it in terms of 2015, 2016, 2017.

“It’s not because the regime is so strong or the opposition is so weak. It’s because this has become a much bigger conflict than just Syria,” Nerguizian says. “This is a conflict where a lot of scores are being settled. You have an influx of forces that are increasingly radical ….”

He says President Bashar al-Assad’s regime is now getting help from Iran, Russia and factions in Lebanon, and is learning how to fight an effective counter-insurgency war. The fighting, he adds, is settling into a drawn-out war of attrition.

According to the United Nations, the fighting so far has killed an estimated 70,000 and displaced more than five million.

“Frankly, I can imagine a much higher death toll,” said Nerguizian. He compared the fighting to the 15-year civil war in neighboring Lebanon that took an estimated 120,000 lives between 1975 and 1990.

The truth is not on Twitter

Predictions of Assad’s downfall aside, many experts are now saying it’s impossible to predict how the civil war will turn out.

Joshua Landis, director of the Middle East Studies Center at the University of Oklahoma, even describes the outcome of the 22-month revolution as “a crap shoot.”

Nerguizian also is cautious when it comes to predicting how the civil war will turn out.

“We don’t really know a great deal about where the truth lies in terms of what the regime is capable of and the same for the opposition," he says. “We’re living in this Twitter, Facebook and instant media universe that makes us feel like we are active participants …… when in reality we have no direct link.”

Both Assad’s regime and the opposition engage in extensive propaganda. The regime’s theme is its eventual victory. The opposition makes similar claims and talks about points and tipping points.

“Both sides – the Assad regime and its opponents – are involved in a liars’ contest,” Nerguizian said. “And frankly that’s actually worked into the battle strategies of both sides.”

As an example, he says Assad has used predictions of his weakness and eventual defeat to lure the opposition into overly aggressive and ill-considered military tactics. Then Assad’s forces launch fierce counter-attacks. The ploy, Nerguizian says, is similar to Russian strategies in Chechnya.

Who controls Syria right now?

On a map of Syria, the rebels control most of the landscape. But the government continues to hold Damascus and the cities of Homs and Hama to the north of the capital, two Mediterranean coastal regions including the port cities of Tartus and Latakia, and part of Aleppo, the largest city in the country.

“They own Damascus,” said Landis. “They own the downtown parts of almost every city.”

Opposition brigades now control many low-income suburbs and half of the nation’s large commercial city of Aleppo, “but the Christian quarters, the upper-class quarters are still in government hands and it’s difficult for the opposition to make those sorts of inroads because they will lose a lot of people…,” Landis said.

Assad forces have withdrawn from a large eastern Kurdish region and are under pressure in the Jazeera region’s major city, Deir al-Azzour.

Nerguizian believes, however, that the battles are far from over.

“For all the talk of Aleppo falling to the opposition, you have basically had a divided city for going on seven months now,” he said. “You’re going to see a much stronger resistance in the centers like Damascus.”

Experts now describe Assad waging a war of attrition. The strategy is to wear down the opposition, retreat when necessary and deny the other side victory. And instead of sending ground troops into hostile areas of the big cities, the army uses artillery to bombard rebel-held neighborhoods from a safe distance.

Iran and Russia remain reliable donors to Assad’s war effort, according to Syrian dissident and expatriate blogger Ammar Abdulhamid.

“Without continuing arms supplies from both countries, and funds from Iran and Iraq, the regime would have collapsed by now,” he says.

Assad’s forces also are getting help from Iran’s Quds Force fighters and Hezbollah, the militants based in Lebanon. Nerguizian said Hezbollah is protecting the Shi’a shrine at Zeinab, Shi’a villages in the Bekaa Valley and a crucial highway link between Beirut and Damascus.

The Washington Post also reports that Hezbollah and Quds advisors in the Zabadani area are training newly recruited Alawites for Assad’s pro-government shabiha militia.

"Sitting on the fence" to avoid the bombs

Syria experts say foreign governments that support the anti-Assad revolution often fail to appreciate that the Syrian leader still has widespread support, not only among the Alawite minority, but among many Sunni Muslims who have been able to take advantage of the economic opportunities of the Ba’athist Party state.

“The side of this that we don’t like to talk about is that the fact that you have still far too much support for this regime,” said Nerguizian, adding that there are “way too many Syrians in a population of 22 million people who frankly are sitting on the fence or are quietly rooting for whoever brings stability.”

Landis said fear is a major factor in this apparent loyalty to Assad.

“Lots of the upper class cling to him because they don’t want to get bombed by Syrian jet airplanes,” he said.

Assad draws most of his strength from his fellow-Alawites who share leadership of the nation.

“Syria is led by cousins and in-laws,” Landis said. “Traditional family values and a different kind of glue, a sectarian family of glue.”

Even as rebel forces have moved into the suburbs of Damascus and are trying to close in on the capital’s center, some experts on the civil war say it could drag on for another four years.

“I don’t look at this conflict in terms of ending in 2013,” said Aram Nerguizian, a Syria expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington D.C. research organization. “I look at it in terms of 2015, 2016, 2017.

“It’s not because the regime is so strong or the opposition is so weak. It’s because this has become a much bigger conflict than just Syria,” Nerguizian says. “This is a conflict where a lot of scores are being settled. You have an influx of forces that are increasingly radical ….”

He says President Bashar al-Assad’s regime is now getting help from Iran, Russia and factions in Lebanon, and is learning how to fight an effective counter-insurgency war. The fighting, he adds, is settling into a drawn-out war of attrition.

According to the United Nations, the fighting so far has killed an estimated 70,000 and displaced more than five million.

“Frankly, I can imagine a much higher death toll,” said Nerguizian. He compared the fighting to the 15-year civil war in neighboring Lebanon that took an estimated 120,000 lives between 1975 and 1990.

The truth is not on Twitter

Predictions of Assad’s downfall aside, many experts are now saying it’s impossible to predict how the civil war will turn out.

Joshua Landis, director of the Middle East Studies Center at the University of Oklahoma, even describes the outcome of the 22-month revolution as “a crap shoot.”

Both sides – the Assad regime and its opponents – are involved in a liars’ contestAram Nerguizian, Center for Strategic International Studies

“We don’t really know a great deal about where the truth lies in terms of what the regime is capable of and the same for the opposition," he says. “We’re living in this Twitter, Facebook and instant media universe that makes us feel like we are active participants …… when in reality we have no direct link.”

Both Assad’s regime and the opposition engage in extensive propaganda. The regime’s theme is its eventual victory. The opposition makes similar claims and talks about points and tipping points.

“Both sides – the Assad regime and its opponents – are involved in a liars’ contest,” Nerguizian said. “And frankly that’s actually worked into the battle strategies of both sides.”

As an example, he says Assad has used predictions of his weakness and eventual defeat to lure the opposition into overly aggressive and ill-considered military tactics. Then Assad’s forces launch fierce counter-attacks. The ploy, Nerguizian says, is similar to Russian strategies in Chechnya.

Who controls Syria right now?

On a map of Syria, the rebels control most of the landscape. But the government continues to hold Damascus and the cities of Homs and Hama to the north of the capital, two Mediterranean coastal regions including the port cities of Tartus and Latakia, and part of Aleppo, the largest city in the country.

“They own Damascus,” said Landis. “They own the downtown parts of almost every city.”

Opposition brigades now control many low-income suburbs and half of the nation’s large commercial city of Aleppo, “but the Christian quarters, the upper-class quarters are still in government hands and it’s difficult for the opposition to make those sorts of inroads because they will lose a lot of people…,” Landis said.

Assad forces have withdrawn from a large eastern Kurdish region and are under pressure in the Jazeera region’s major city, Deir al-Azzour.

Nerguizian believes, however, that the battles are far from over.

“For all the talk of Aleppo falling to the opposition, you have basically had a divided city for going on seven months now,” he said. “You’re going to see a much stronger resistance in the centers like Damascus.”

Experts now describe Assad waging a war of attrition. The strategy is to wear down the opposition, retreat when necessary and deny the other side victory. And instead of sending ground troops into hostile areas of the big cities, the army uses artillery to bombard rebel-held neighborhoods from a safe distance.

Iran and Russia remain reliable donors to Assad’s war effort, according to Syrian dissident and expatriate blogger Ammar Abdulhamid.

“Without continuing arms supplies from both countries, and funds from Iran and Iraq, the regime would have collapsed by now,” he says.

Lots of the upper class cling to him because they don’t want to get bombed by Syrian jet airplanesJoshua Landis, Center for Middle Eastern Studies

The Washington Post also reports that Hezbollah and Quds advisors in the Zabadani area are training newly recruited Alawites for Assad’s pro-government shabiha militia.

"Sitting on the fence" to avoid the bombs

Syria experts say foreign governments that support the anti-Assad revolution often fail to appreciate that the Syrian leader still has widespread support, not only among the Alawite minority, but among many Sunni Muslims who have been able to take advantage of the economic opportunities of the Ba’athist Party state.

“The side of this that we don’t like to talk about is that the fact that you have still far too much support for this regime,” said Nerguizian, adding that there are “way too many Syrians in a population of 22 million people who frankly are sitting on the fence or are quietly rooting for whoever brings stability.”

Landis said fear is a major factor in this apparent loyalty to Assad.

“Lots of the upper class cling to him because they don’t want to get bombed by Syrian jet airplanes,” he said.

Assad draws most of his strength from his fellow-Alawites who share leadership of the nation.

“Syria is led by cousins and in-laws,” Landis said. “Traditional family values and a different kind of glue, a sectarian family of glue.”