Every year, about one million people visit the town of Deadwood in the Black Hills of South Dakota — once one of the wildest and most lawless towns of America's Old West.

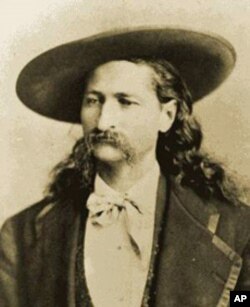

Wild Bill Hickok, for instance, was a celebrated Deadwood gambler and gunman who was shot dead while dealing cards in a poker game.

Deadwood Dick, a black man, was one of the most accurate shots in the West. He could shoot a wart off your nose.

And Calamity Jane Burke was a hard-drinking harlot with a heart of gold.

So Deadwood was quite the rip-roaring town. And it's no ghost town today. It's thriving, thanks to historic attractions, games of chance, and an unusual commitment to preservation.

Many citizens of Deadwood — which got its name from a stand of trees burned in a forest fire — got rich in 1876 as the cry of gold!! filled Deadwood Gulch in the Black Hills.

For a while, Deadwood was a sumptuous Victorian showplace of 25,000 people, with fine hotels and restaurants and electricity.

But it deteriorated over the decades, and by the 1980s, tourists were demanding better than Wild West joints with neon signs and fake knotty-pine facades.

It was then that the town commissioners decided to fix up Deadwood and make it a genuine historic attraction rather than a phony one.

A South Dakota architect came in and restored the historic Bodega Saloon and several other Deadwood buildings.

And the town commissioners proposed a neat way to pay for all these improvements.

Voters all across South Dakota approved a measure allowing low-stakes gambling in Deadwood.

Low stakes, meaning inexpensive slot machines and maximum $25 bets on poker.

More than half of the gaming profits would go directly to the town for architectural restoration. That turned into millions of dollars a year, and the gaming parlors now employ more people than live in Deadwood.

So gambling and historic preservation became, in the words of one preservationist, Deadwood's Siamese twins. You cannot separate them.