Native Americans

Tribal Courts Across US Expanding Holistic Alternatives to Criminal Justice System

Inside a jail cell at Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, Albertyn Pino's only plan was to finish the six-month sentence for public intoxication, along with other charges, and to return to her abusive boyfriend.

That's when she was offered a lifeline: An invitation to the tribe's Healing to Wellness Court. She would be released early if she agreed to attend alcohol treatment and counseling sessions, secure a bed at a shelter, get a job, undergo drug testing and regularly check in with a judge.

Pino, now 53, ultimately completed the requirements and, after about a year and a half, the charges were dropped. She looks back at that time, 15 years ago, and is grateful that people envisioned a better future for her when she struggled to see one for herself.

"It helped me start learning more about myself, about what made me tick, because I didn't know who I was," said Pino, who is now a case manager and certified peer support worker. "I didn't know what to do."

The concept of treating people in the criminal justice system holistically is not new in Indian Country, but there are new programs coming on board as well as expanded approaches. About one-third of the roughly 320 tribal court systems across the country have aspects of this healing and wellness approach, according to the National American Indian Court Judges Association.

Combining legal advocacy and support

Some tribes are incorporating these aspects into more specialized juvenile and family courts, said Kristina Pacheco, Tribal Healing to Wellness Court specialist for the California-based Tribal Law and Policy Institute. The court judges association is also working on pilot projects for holistic defense — which combine legal advocacy and support — with tribes in Alaska, Nevada and Oklahoma, modeled after a successful initiative at the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana.

"The thought and the concept will be different from tribe to tribe," said Pacheco. "But ultimately, we all want our tribal people ... to not hurt, not suffer."

People in the program typically are facing nonviolent misdemeanors, such as a DUI, public intoxication or burglary, she said. Some courts, like in the case of Pino, drop the charges once participants complete the program.

A program at the Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe in Washington state applies restorative principles and assigns wellness coaches to serve Native Americans and non-Natives in the local county jail, a report released earlier this year by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation outlined. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma has a reintegration program that includes financial support and housing services, as well as cultural programming, career development and legal counsel. In Alaska, the Kenaitze Indian Tribe's wellness court helps adults in tribal and state court who are battling substance abuse and incorporates elements of their tribe's culture.

"There's a lot of shame and guilt when you're arrested," said Mary Rodriguez, staff attorney for the court judges association. "You don't reach out to those resources, you feel that you aren't entitled to those resources, that those are for somebody who isn't in trouble with the law."

'You are better than the worst thing you've done'

"The idea of holistic defense is opening that up and reclaiming you are our community member, we understand there are issues," Rodriguez said. "You are better than the worst thing you've done."

The MacArthur Foundation report outlined a series of inequities, including a complicated jurisdictional maze in Indian Country that can result in multiple courts charging Native Americans for the same offense. The report also listed historical trauma and a lack of access to free, legal counsel within tribes as factors that contribute to disproportionate representation of Native Americans in federal and state prisons.

Advocates of tribal healing to wellness initiatives see the approaches as a way to shift the narrative of someone's life and address the underlying causes of criminal activity.

There isn't clear data that shows how holistic alternatives to harsh penalization have influenced incarceration rates. Narrative outcomes might be a better measure of success, including regaining custody of one's children and maintaining a driver's license, said Johanna Farmer, an enrolled citizen of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota and a program attorney for the court judges association.

Some tribes have incorporated specific cultural and community elements into healing, such as requiring participants to interview their own family members to establish a sense of rootedness and belonging.

"You have the narratives, the stories, the qualitative data showing that healing to wellness court, the holistic defense practices are more in line with a lot of traditional tribal community practices," Farmer said. "And when your justice systems align with your traditional values or the values you have in your community, the more likely you're going to see better results."

While not all of these tribal healing to wellness programs have received federal funding, some have.

Between 2020 and 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice distributed more than a dozen awards that totaled about $9.4 million for tribal healing to wellness courts.

This year, the Quapaw Nation in Oklahoma started working on a holistic defense program after seeing a sharp increase in cases following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said a large area of eastern Oklahoma remains a Native American reservation.

So far this year, about 70 cases have been filed, up from nearly a dozen in all of 2020, said Corissa Millard, tribal court administrator.

"When we look at holistic approaches, we think, 'What's going to better help the community in long term?'" she said. "Is sending someone away for a three-year punishment going to be it? Will they reoffend once they get out? Or do you want to try to fix the problem before it escalates?"

For Pino, the journey through Laguna Pueblo's wellness court wasn't smooth. She struggled through relapses and a brief stint on the run before she found a job and an apartment to live in with her son nearby in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her daughters live close by.

She largely credits the wellness court staff for her ability to turnaround her life, she said.

"They were the ones that stood by me, regardless of what I was choosing to do; that was the part that brought me a lot of hope," she said. "And now where I'm at, just to see them happy, it gets emotional, because they never let go. They never gave up on me."

See all News Updates of the Day

Native American news roundup, Feb. 16-22, 2025

Native American tribes report federal funding delays

Some Native American tribes are having difficulties accessing funds for essential services following delays surrounding a temporary White House freeze on thousands of federal programs pending the new administration’s review.

Public Law 93-638, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, is the vehicle through which tribes contract with the federal government to manage most health and education programs that were operated by the government before 1975.

While funds for 638 contracts are now unfrozen, some tribes reported having problems accessing the funding online.

"Tribal nations have candidly shared with me that at first, [online] funding portals were frozen. Even after they opened, funding requests went unanswered for days and weeks,” Sault Ste. Marie tribal council member Aaron Payment told VOA.

The former first vice president of the National Congress of American Indians said tribes remain uncertain about the stability of funding for community health, education and nutrition.

"As it is, we are far underfunded despite our having prepaid for every penny with the nearly 2 billion acres of land that made this country great," Payment said.

Read more:

Federal cuts force layoffs at Native American colleges

The Board of Regents of Haskell Indian Nations University is asking Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to waive staff reductions that would cut nearly 40 employees across teaching, IT and administrative departments.

“Haskell is an important part of the federal government’s commitment to enhancing the quality of life for Indian people,” the board’s letter reads in part.

Haskell in Kansas and Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute (SIPI) in New Mexico are both facing challenges in the new administration’s budget cuts, with Southwestern Indian Polytechnic losing 20 employees.

Those reductions leave 80 staff for 200 students at the New Mexico school and 125 staff for nearly 900 students at Haskell.

"It's affecting Native American students because at the end of the day, it's our generation of students who are going to be contributing to tomorrow's society," SIPI staff member Luke Gibson (Navajo) told Alburquerque's KOB TV. "If we don't invest in Native American education today, how will be useful to our own communities when we want to?"

While the Indian Health Service saw some layoffs temporarily reversed, there has been no similar relief for those universities. Haskell administrators told students that efforts are underway to maintain operations despite lower staffing.

Read more:

Supporters celebrate Leonard Peltier’s homecoming

Native American activist Leonard Peltier returned to the Turtle Mountain Reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota, Tuesday after 49 years in federal prison.

U.S. President Joe Biden commuted Peltier’s sentence last month in one of the last acts of his presidency.

“He is now 80 years old, suffers from severe health ailments, and has spent the majority of his life (nearly half a century) in prison,” Biden said in a January 20 statement. “This commutation will enable Mr. Peltier to spend his remaining days in home confinement but will not pardon him for his underlying crimes.”

Peltier, who is Anishinaabe and Dakota, was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of two federal agents during a 1975 standoff on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He was given two consecutive life sentences.

Peltier supporters say he was framed. Federal law enforcement remains convinced of his guilt, with then-FBI Director Christopher Wray urging Biden “in the strongest terms possible” against granting Peltier clemency.

Read more:

South Dakota Senate says no to mandatory Native studies in public schools

South Dakota lawmakers have rejected a bill that would have required the state’s public schools to teach Native American content known as “Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings.”

“Oceti Sakowin” translates as “People of Seven Council Fires,” an alliance of seven nations that were once known as the Great Sioux Nation.

The curriculum was developed over 10 years as a framework for cultural exchange in South Dakota, where Dakota, Lakota and Nakota tribes are spread out among nine reservations.

Currently, teaching Native American history is optional in South Dakota, with educators reporting that more than half of the state’s teachers already include it in their lesson plans.

Governor Larry Rhoden this week signed a bill requiring all certified teachers to take a course in South Dakota Native American studies.

Read more:

Trump backs Lumbee Tribe's long-standing quest for federal recognition

U.S. President Donald Trump wants Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to come up with a plan to grant the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina what he calls “long overdue” federal recognition, fulfilling a campaign promise he made last September.

Federal recognition acknowledges a tribe’s historic existence and its modern status as a “nation within a nation” entitled to govern itself and receive federal benefits, including health care, housing and education.

Historically, tribes were recognized through treaties or laws or presidential orders or court decisions. In 1978, the Department of the Interior standardized those procedures, allowing recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Congress or a federal court ruling.

Those standards require tribes to demonstrate continuous political autonomy since the 19th century, and members must document descendance from historical tribe members.

The process is time-consuming and expensive, often requiring assistance from historians, genealogists and attorneys. Historic records, if they ever existed, may be lost or destroyed.

The 1978 rules, updated in 1994, also state that tribes previously denied cannot reapply.

‘Gray eyes’

Over time, the Lumbee have been linked to several historic tribes, including the Cheraw, Tuscarora and even Siouan tribes.

“One tribal name or a single cultural origin is insufficient to explain Lumbee history, because Lumbee ancestors belonged to many of the dozens of nations that lived in a 44,000-square-mile territory,” writes Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery. “The names of these diverse communities varied depending on where the people lived and on what Europeans wrote down about them.”

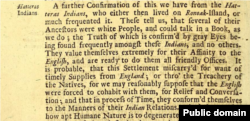

In 1584, English explorer Arthur Barlowe noted that some Indian children on Roanoke Island had “very fine auburn and chestnut coloured hair.”

Three years later, England established a small colony on the island. The governor left for England to gather supplies. When he returned, no one was there. There were two clues: the word "CROATOAN" carved into a fence post and "CRO" on a tree. This gave rise to the theory that they had been taken in by Croatan Indians.

In the early 1700s, Hatteras Indians at Roanoke, as the Croatans were now called, told English explorer John Lawson that they descended from those vanished settlers. They also had “gray eyes,” which Lawson believed confirmed their mixed heritage.

“They tell us, that several of their ancestors were white people, and could talk in a book [read], as we do, the truth of which is confirmed by gray eyes being found frequently amongst these Indians, and no others,” Lawson wrote.

Enduring names

The 1790 federal Census recorded family names found among the Lumbee today and classified them as “all other free persons.”

In 1835, North Carolina banned voting in state elections for anyone who had a Black, mixed-race or biracial ancestor within the past four generations, and the state amended its constitution to segregate Black and white children into separate public schools.

“As the lines between ‘white’ and ‘colored’ hardened in North Carolina … Indians resolved that non-Indians must recognize their distinct identity,” Lowery wrote.

In 1885, North Carolina recognized the Lumbee as “Croatan” Indians and created separate schools for them. Shortly after, 54 members identifying themselves as Croatan Indians and “remnants” of the lost colony petitioned Congress for aid to educate more than 1,100 of the tribe’s children.

The Indian Affairs commissioner turned them down, saying he could barely afford to support the tribes already recognized, let alone the Croatans.

The tribe renamed itself “Lumbee,” after the nearby Lumber River, in 1952. In 1956, Congress passed Public Law 570, acknowledging the tribe as a mix of colonial and coastal-Indian blood but denying them federal benefits.

In the 1990s, the Interior Department again rejected the Lumbee’s petition, citing insufficient proof of cultural, political or genealogical ties to a specific historic tribe. Despite failed bills, the House passed the Lumbee Fairness Act in December 2024, which, if approved by the Senate, would grant federal recognition and benefits.

The Interior Department released an update to the acknowledgment process, allowing certain tribes that were previously denied the opportunity to reapply for recognition. That was set to take effect this week but has been postponed to March 21.

Congress 'not equipped'

North Carolina’s federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) has long opposed Lumbee recognition.

“The Lumbee cannot even specify which historical tribe they descend from, and recent research has underscored the dangers of legislative recognition without proper verification,” EBCI principal chief Michell Hicks said in a December 2024 statement. “Allowing this bill [the Lumbee Fairness Act] to pass would harm tribal nations across the country by creating a shortcut to recognition that diminishes the sacrifices of tribes who have fought for years to protect their identity.”

Former EBCI chief Richard Sneed told VOA in 2022, “Congress is not equipped to do the necessary research to determine whether or not a group is a historic tribe or not. The process was created for that purpose.”

In an emailed statement, Lumbee tribal chairman John L. Lowery expressed cautious optimism that the Lumbee Fairness Act would pass.

“Our critics are sad individuals who use racist propaganda to discredit us while ignoring the struggles of other minorities in America,” he told VOA. “As Indigenous people, we are the minority of the minority here in the United States, and our critics are trying to erase the memories of our ancestors, and we will not let that happen!”

Fifty-six thousand people identified as Lumbee in the 2020 U.S. Census. If recognized, they would be the largest acknowledged tribe east of the Mississippi River.

Native American news roundup, Feb. 2-8, 2025

Native American groups this week expressed concern that some of U.S. President Donald Trump’s executive orders could challenge tribal sovereignty and Native citizenship.

Executive orders signed on Jan. 20 crack down on illegal immigration to the U.S. and mobilize federal law enforcement agencies and the U.S. military to stop, question and detain undocumented immigrants to achieve “complete control” of the southern border.

Navajo spokesperson Crystaline Curley told CNN that tribal citizens were being caught up in immigration sweeps, although she did not give a number. A Navajo citizen reported she had been questioned during an office raid in Scottsdale, Arizona, but was released after presenting her Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood.

Border czar Tom Homan told reporters Thursday that immigration enforcement operations are now focusing on criminal migrants, but “as the aperture opens up beyond criminals, you are going to see more arrests. I’ve made it clear: If you are in the country illegally, you are not off the table.”

In a statement to Newsweek, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement said its agents may encounter U.S. citizens during raids and will request identification to confirm their identities.

Tribes nationwide are encouraging members to carry tribal identification cards and Certificates of Degree of Indian Blood, which are issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and document a person's degree of Indian ancestry within a specific federally recognized tribe.

Some Natives worry US citizenship under federal scrutiny

A federal judge in Seattle, Washington, in January blocked Trump’s executive order denying automatic U.S. citizenship to babies born after Feb. 19, 2025, unless they have at least one parent who is either a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident. The order was paused indefinitely this week by a federal judge in Maryland.

That case was closely watched by Native Americans because U.S. Justice Department lawyers cited the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which excluded "Indians not taxed" from citizenship, and an 1880 Supreme Court decision that Native Americans were not birthright citizens. That 1880 decision centered on a Native American man in Nebraska who the court ruled owed allegiance to his tribe and was not a birthright citizen with the right to vote.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States.

Native groups, fearing funding freeze, remind White House of its federal obligations

Native American tribal groups wrote the new president about actions that could freeze or mislabel tribal funding.

“Our unique political and legal relationship with the United States is rooted in our inherent sovereignty and recognized in the U.S. Constitution, in treaties, and is carried out by many federal laws and policies,” the Feb. 2 letter reads.

The letter calls on the Trump administration to respect tribal nations as political entities, continue direct consultations, ensure federal workforce changes don’t disrupt services and keep tribal-focused offices in federal agencies.

It specifically warns against treating tribal programs as general diversity or environmental initiatives and invites government officials and Congress to discuss these issues further.

Interior secretary Burgum sworn in, stresses commitment to tribes

Doug Burgum was sworn in as secretary of the Interior Department on Jan. 31. He thanked Trump and stressed his history of working with Native American tribes during his tenure as North Dakota governor.

“In North Dakota, we share geography with five sovereign tribal nations. The current partnership is historically strong because we prioritized tribal engagement through mutual respect, open communication, collaboration and a sincere willingness to listen,” Burgum said. “At Interior, we will strengthen our commitment to enhancing the quality of life, promoting economic opportunities and empowering our tribal partners through those principles.”

Burgum has the support of several tribal leaders, including Mark N. Fox, who chairs the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota; Chuck Hoskin Jr., principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma; and Bobby Gonzalez, chair of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma.

Burgum on Monday hit the ground running with a series of orders advancing Trump’s energy agenda.

Secretarial order 3417 directs all Department of the Interior bureaus and offices to create a 15-day plan detailing how they can speed up energy resource development, from initial identification through production, transportation and export. The directive pays special attention to federal lands, the Outer Continental Shelf and specific regions that include the West Coast, Northeast and Alaska.

Secretarial Order 3418 calls for a 15-day review of public lands that the Biden administration withdrew from resource extraction, including national monuments of historic, cultural and spiritual importance to tribes.

“Among the sites most at risk are Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments in Utah,” Indian Country Today reported this week, noting that Grand Staircase-Escalante holds large coal reserves, and the Bears Ears area has uranium.

Read more:

Navajo nominated as DOI Indian Affairs Secretary

The National Congress of American Indians this week supported the White House nomination of Navajo citizen William “Billy” Kirkland III to serve as the Interior Department’s assistant secretary of Indian Affairs. If confirmed, he would head the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

"NCAI looks forward to engaging with Kirkland upon his confirmation to protect and further strengthen the government-to-government relationship and advance policy priorities that support Tribal Nations," said a statement from NCAI President Mark Macarro. "We remain committed to working in partnership with the Department of the Interior to uphold tribal sovereignty."

Native American media note that the nomination, as cited in the Congressional Record, lists the position as “Assistant Secretary of the Interior vice [“in place of”] Bryan Todd Newland, resigned."

Previously, the position was called “Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs.”

Kirkland’s nomination has been referred to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.

Read more:

Defense Department: Identity months ‘erode camaraderie’

The U.S. Defense Department this week issued a policy banning the use of official resources or work hours to host cultural heritage celebrations. These include National American Indian Heritage Month and Asian American and Pacific Islander Month.

“Our unity and purpose are instrumental to meeting the Department's warfighting mission,” the directive reads. “Efforts to divide the force — to put one group ahead of another — erode camaraderie and threaten mission execution.”

While official events are no longer permitted during work hours, service members may still attend such events unofficially during their personal time.

“We are proud of our warriors and their history, but we will focus on the character of their service instead of their immutable characteristics,” the new policy states.

Read the directive here:

Native American news roundup, Jan. 19-25, 2025

Senate Energy Committee approves Trump's pick to lead Department of Interior

The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee this week voted 18-2 to approve the nomination of North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum to head the as U.S. Department of Interior.

If the full Senate approves, Burgum will oversee 11 bureaus and agencies that manage public lands, minerals, national parks and wildlife refuges. He will also oversee federal trust responsibilities to Indian tribes and Native Alaskans.

During his confirmation hearing, Burgum stressed that he has the support of his state’s five tribes.

“State and tribal relationships in North Dakota have sometimes been challenged, but the current partnership is historically strong because we prioritize tribal engagement through mutual respect,” Burgum told senators.

In addition to the Interior Department, President Donald Trump wants Burgum to lead a new national energy council.

Burgum has said he backs bypassing certain environmental regulations to increase energy production, create jobs and enhance national security. He also stressed his commitment to land conservation.

“We always want to prioritize those areas that have the most resource opportunity for America with the least impact on lands that are important, and I think that’s a pretty simple formula to be able to figure out,” Burgum said during his hearing.

Trump Pursues Recognition for Lumbee Tribe

Fulfilling a campaign promise he made to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina last September, President Donald Trump this week directed the interior secretary to initiate steps toward securing full federal recognition for the tribe.

Historically, the tribe has been known by several names, including Tuscarora, Croatan, Cheraw and Cherokee. In 1953, it changed its name from "Cherokee Indians of Robeson County" to the "Lumbee Indians of North Carolina."

North Carolina recognized the Lumbee Tribe in 1885. In 1956, Public Law 570, the "Lumbee Act," acknowledged the tribe as an "admixture of colonial blood with certain coastal tribes of Indians" but denied it federal services. In the 1990s, the Interior Department rejected the tribe's petition for recognition, saying it could not document cultural, political or genealogical ties to any single historic tribe.

Biden grants clemency to Leonard Peltier

In the last hours of his presidency, President Joe Biden on Sunday commuted the life sentence of Indigenous activist Leonard Peltier, who was convicted in the 1975 killings of two FBI agents. He has served almost 50 years in prison.

During the unrest of the 1970s, Peltier, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, joined the American Indian Movement, or AIM, which was dedicated to protecting, preserving and defending treaty rights of tribal Americans. AIM’s reputation was tarnished by acts of violence, most notably the 1972 six-day takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington.

In 1977, Peltier was convicted of the 1975 murders of two FBI agents during a standoff on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

“He is now 80 years old, suffers from severe health ailments, and has spent the majority of his life (nearly half a century) in prison,” the Biden White House said in a statement. “This commutation will enable Mr. Peltier to spend his remaining days in home confinement but will not pardon him for his underlying crimes.”

A diverse coalition of tribal nations, human rights groups and former law enforcement officials support his release, scheduled for Feb. 18.

The FBI tried to block his release.

“Peltier is a remorseless killer, who brutally murdered two of our own,” former FBI Director Christopher Wray wrote in a letter to Biden on Jan. 10. “Mr. President, I urge you in the strongest terms possible: Do not pardon Leonard Peltier or cut his sentence short.”

Also in 1975, Annie Mae Pictou-Aquash, a Mi'kmaq activist and AIM member from Nova Scotia, Canada, was kidnapped, raped and murdered. A 35-year investigation resulted in convictions of two other AIM members, but her family and supporters believe that Peltier was involved with her killing and expressed disappointment over his release.

Wearable robot teaches endangered Indigenous languages

In the tech world, Native Americans are almost invisible.

Danielle Boyer is looking to change that. The 24-year-old Anishinaabe robotics inventor from the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Michigan founded the nonprofit STEAM Connection in 2019 to design, manufacture and donate educational robots to Indigenous students.

Her latest creations, called SkoBots, are wearable animal-shaped robots that help students learn endangered Indigenous languages.

Boyer has distributed 20,000 free robot kits to Indigenous students, advocated for youth in STEM fields and challenged stereotypes about Indigenous peoples' technological capabilities.

Read more:

Native American news roundup, Jan. 5-11, 2025

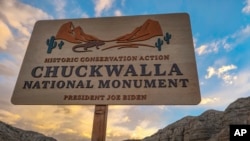

Tribes laud Biden designation of national monuments in California

President Joe Biden this week announced plans to designate two new national monuments in California as part of his “America the Beautiful” initiative to conserve at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030.

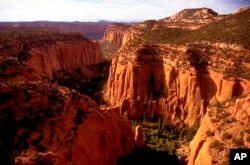

The Chuckwalla National Monument in the southern desert region encompasses about 260,000 hectares (624,000 acres) near Joshua Tree National Park on the ancestral lands of the Iviatim, Nüwü, Pipa Aha Macav, Kwatsáan, and Maara’yam peoples – today, the Cahuilla, Chemehuevi, Mojave, Quechan, and Serrano Nations.

“The area includes village sites, camps, quarries, food processing sites, power places, trails, glyphs, and story and song locations, all of which are evidence of the Cahuilla peoples’ and other Tribes’ close and spiritual relationship to these desert lands," Erica Schenk, Chairwoman of the Cahuilla Band of Indians, said in a statement.

To the north, the Sattitla Highlands National Monument will protect 90,650 hectares (224,000) acres of ancestral lands in Shasta-Trinity, Klamath, and Modoc National Forests near Mount Shasta. This region is sacred to the Pit River Nation and will safeguard critical water resources and rare wildlife species.

In Biden’s final days in office, his administration has issued several environmental protections. On Monday, he banned oil and gas drilling in more than 24 million hectares ( 600 million acres) of coastal waters; on Dec. 26, Interior Secretary Deb Haaland instituted a 20-year ban on mining activities in portions of South Dakota’s Black Hills; and on Dec. 30, his administration announced a 20-year withdrawal of all oil, gas and geothermal development in Nevada’s Ruby Mountain area.

Little interest in Arctic oil and gas leases

The Interior Department announced this week that no bids were submitted for the second oil and gas lease sale in the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

This sale, required by the 2017 Tax Act, aimed to generate $2 billion over 10 years but failed to attract interest. The first sale was held under the Trump administration and also saw little demand, raising only $14.4 million.

All previous leases have been canceled, leaving no active leases in the area.

Interior Department Acting Deputy Secretary Laura Daniel-Davis said the lack of interest shows the Arctic Refuge is too special to risk with drilling.

“The BLM [Bureau of Land Management] has followed the law and held two lease sales that have exposed the false promises made in the Tax Act. The oil and gas industry is sitting on millions of acres of undeveloped leases elsewhere; we’d suggest that’s a prudent place to start, rather than engage further in speculative leasing in one of the most spectacular places in the world.”

Documentary about tribal disenrollment dropped from film festival

Film director Ryan Flynn says he was “elated” in October when his documentary “You’re No Indian” was selected for screening at the 36th annual Palm Springs International Film Festival, which runs through Jan. 13 (see film trailer, above).

The film concerns the growing trend of tribal disenrollment by which some Native American tribes strip individuals and families of their citizenship, making them ineligible for federal benefits and services and, as the documentary stresses, shares in casino revenue.

“When they announced the film schedule, we sold out on the first day,” Flynn said. “And then in mid-December, we got an email saying there had been a scheduling error, and they wouldn’t be able to move forward with our screening.”

Flynn said he was heartbroken.

“I don't mean heartbroken for myself,” he said. “It's for the people whose voices you have been systematically silenced by the powers that be.”

Indigenous rights attorney Gabe Galanda, a citizen of the Round Valley Indian Tribes in California, told VOA that approximately 10,000 tribal citizens from almost 100 tribes have been disenrolled.

VOA reached out to the film festival for comment.

“Due to an unforeseen scheduling error, the festival was unable to proceed with screenings of the film YOU’RE NO INDIAN,” a spokesperson responded via email. “The festival programming team reached out to the filmmaker to explain the situation and offered to reimburse the director for any non-refundable festival travel fees that may have been incurred.”

Federal report shows Native Americans wrongfully billed for health care

Native Americans are twice as likely to have medical debt sent to collections, with average debts that are one-third higher than the national average. This problem is worsened by limited access to year-round health care through the Indian Health Service and inconsistent Medicaid coverage between states, reports the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The IHS is responsible for providing free health care services in regional clinics. Where specialty services aren’t available, patients may be approved for emergency care outside the program at no cost.

Errors in bill processing and payment delays mean Native individuals are frequently billed for debts they should not owe, the consumer protection bureau says. Improper medical debt can damage individuals’ credit, making them ineligible for jobs, housing, loans and educational opportunities.

The Indian Health Service is responsible for providing free health care services in regional clinics. Where specialty services aren’t available, patients may be approved for emergency care outside the program at no cost.

![“A chief lord of Roanoac [Roanoke]" from Theodor de Bry’s Engravings for Thomas Harriot’s Briefe and True Report (1590).](https://gdb.voanews.com/9de27047-b11f-4db2-f7b5-08dd4a817620_w250_r0_s.jpg)