This is Part 1 of a 5-part series: Honoring Africa’s Traditional Music

Continue to Parts 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

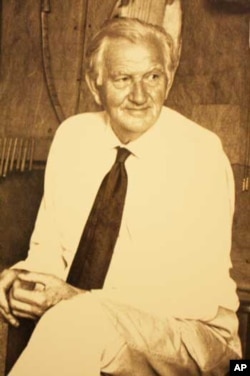

When a young Englishman arrived in what was then Rhodesia in 1921 to run a tobacco farm, his workers expected him to be just like the other colonial overlords they’d known. He would be their master; they would be his servants. They would obey his every command, and they would speak to him only when he spoke to them.

After all, he was white and they were black. They were dependent on him for their daily bread. Rhodesia was ruled by the British, and the country’s black people had no rights whatsoever.

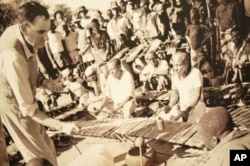

But, from their first interaction with him, Hugh Tracey’s laborers saw that he was different. Besides immediately learning the Karanga dialect of their Shona language and sweating with them at work in the fields, the farmer constantly asked them about their culture…and especially their music. Tracey learned Shona folksongs and sang along with his workers as they toiled together among the tobacco crops.

“Music was the gateway for my father into African’s lives. It was his experience in (now) Zimbabwe that sparked his life’s work, his life’s love,” said Andrew Tracey, who followed in his father’s footsteps to become one of the world’s top ethnomusicologists.

Resistance

However, when Hugh suggested to various colonial authorities that African music was “important,” said his son, he met resistance. “He was staggered to find that there was no interest from anybody – whether in the church, or in education, or in government or even among the other farmers – in this African music.”

But, said Andrew, his father maintained that the music of Africa was “deep and of immense cultural value. So he thought, ‘This needs to be studied; it needs to be recorded and revealed (to the world).’ So the rest of his life he spent revealing and discovering African music.”

Hugh Tracey is currently being honored in South Africa, with an exhibition that celebrates his life. From the 1920s until his death in 1977, he accumulated what international musicologists consider to be the world’s most valuable and extensive record of traditional African music.

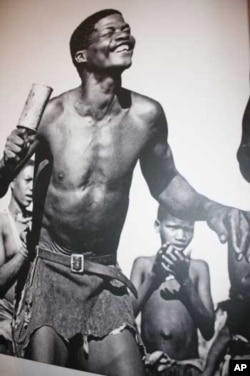

In his lifetime, Hugh traversed sub-Saharan Africa – from the deserts of then South West Africa, now Namibia, to the jungles of the Congo, to the plains of Nyasaland, now Malawi, to the Swahili coasts of Kenya and Tanzania – to record indigenous music.

“Hugh Tracey was someone who did not enjoy the benefit of a university education or the kind of academic training that most music scholars have. But he had an innate ability to see what needed to be done (to preserve African music), which was truly remarkable.” said Prof. Diane Thram, director of the International Library of African Music in South Africa. The institution is home to Hugh Tracey’s recordings.

‘Simply unbelievable’

In the mid 1930s, inspired by his passion for the sounds of Africa and his self-taught knowledge of sound recording, Hugh abandoned farming. He joined the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) in Durban, on South Africa’s east coast, in the country’s then Natal province. There, he immersed himself in the culture of the Zulu people.

“Right from the start of my life I can remember going to African music performances with him…. He used to take me to the Zulu dancing in the interior of Natal and to record music at (Zulu) Chief Buthelezi’s village,” Andrew recalled.

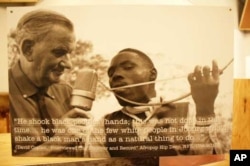

In the late 1930s, Hugh’s close attachment to black people and the value he put on them would have been surprising anywhere in the world. But the fact that he did it in South Africa – at a time when the National Party was preparing to declare actions such as Hugh’s interracial relationships illegal – made his work “all the more shocking, and wonderful,” said Thram.

“Hugh Tracy was truly an exceptional person for his time,” she commented, adding that his later persuasion of the SABC to allow him to devote a weekly radio show to “educating white audiences about black music” at the height of apartheid was “simply unbelievable.

Public ridicule

“White people, especially in South Africa, regarded music made by black Africans to be worthless. So my father’s championing of it meant he was often publicly ridiculed,” Andrew told VOA, emphasizing that this did not deter his father. “There’s always been a certain class of people who’ve been above that sort of petty thinking, and that was the kind of society that we liked to move in – enlightened people,” he stated.

Nevertheless, the entrenchment of apartheid in 1948 made Hugh Tracey’s mission much more complex. Andrew explained, “Apartheid made it against the law for whites to be in places where blacks resided,” in impoverished shantytowns called “locations” and in isolated “tribal homelands.”

It meant Hugh Tracey had to apply for permission from the government every time he wanted to visit an area where black people lived and made music. In order to pursue his mission to record as much indigenous African music as possible, he was willing to do this. But, said Andrew, it led to “misconceptions” about him and his father.

“Certain people started to think that, because we were recording around the country in tribal areas, that we were therefore supporting (apartheid) tribalism, and supporting the rationale of the apartheid government (of the supremacy of whites) – which was far from the case,” he explained.

No help from racists

Andrew said he and his father had never received any support from the state. “Even if we had asked (apartheid government officials) for financial help, they would not have given it because they saw absolutely no value in African culture. Secondly, we did not want their help because we opposed their policies. Almost all the support we got was from overseas foundations (in Britain and the United States).”

In other parts of Africa, Andrew said it was “easier” for him and his father to record music, although they were sometimes “treated with suspicion” by some authorities.

As a result of the Traceys’ passion and perseverance, African music of the ancient past that would have been lost forever has been saved. It’s now available to teach future generations of Africans about their history and heritage.