Asia was 12 when Islamic State militants separated her from her mother and held her for two days. They told her and other young Yazidi girls to get onto a bus.

"They said we were going to the mountains to be set free," she said. "But instead they took us and ruined our lives." As a "wife" to two different militants over the next five years, Asia was forced into grueling slave labor, beaten and raped.

Asia lives in a refugee camp, but she came to her hometown of Kocho on Friday to witness the first exhumation of mass graves from the IS atrocities that killed and enslaved thousands of Yazidi people beginning in August 2014. Thousands more remain missing.

Asia's nightmare ended only a few days ago, when her captor surrendered to Syrian forces in Baghuz, the last sliver of IS's self-proclaimed caliphate in Syria.

But while she was enslaved, her sister, 3, and her two infant brothers were slain, she said.

Most of the roughly 400,000 Yazidi people in Iraq are still displaced, living in crowded camps and scattered around the world. Authorities hope to identify the bodies of people in dozens of mass graves in Iraq, so their remains can be buried by their families.

As Asia told her story, two other local women joined the conversation.

"Are you all right?" one woman asked. "Did you see other girls from Kocho in Syria?"

"What about the boys? Did you see any of them?" added the other.

"I saw some of our girls," she replied. "But I'm sorry. I didn't see any of the boys."

Crisis continues

Asia said that on the same bus that carried her into five years of slavery was another young woman, named Nadia Murad.

IS killed Murad's six brothers, her brothers' children and her mother, and then sold her into sexual slavery. After she escaped, she publicly campaigned to end mass rape in war and went on to win a Nobel Peace Prize last year.

As the United Nations prepared for the first exhumation Friday, Murad spoke to families from her hometown and Iraqi leaders who were all in Kocho for the event.

The crisis for the Yazidi people continues, she said.

"Our bodies have reached a point where we cannot stand any more pain," Murad said. Many areas once densely populated with Yazidi families are still virtually abandoned, lacking security and basic services like running water and electricity.

Besides the poverty that has engulfed their community since IS militants gained and later lost control of vast parts of Iraq and Syria, the current political climate in Iraq also is keeping families displaced, she said. Both the Kurdistan Regional Government, a semi-autonomous government based in Irbil, and the federal government in Baghdad claim the right to control certain portions of Iraq. The back and forth has stymied attempts to develop local governments.

"When our governments did not protect us, we were an easy target for IS," Murad said. "I hope they will find a solution for the disputed areas."

Solace?

The United Nations has called the crimes against the Yazidi people a genocide, and activists say they hope the exhumation will help identify the missing, locate the dead and assist attempts to prosecute IS leaders in international courts.

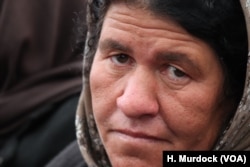

As Fadia Abdullah waited for the events to begin, she said one of her brothers was buried in a mass grave, and another was missing. She recently heard that her 14-year-old nephew was still alive, being held as a slave by militants in Baghuz.

She cannot go back to her house in Kocho, and a tent number in a camp is her only contact information. As many women and some men sobbed, she sat stoically, listening to U.N. and government officials pledge to find her loved ones' bodies.

"It could be a relief," she said, as if it were a question. "We will never be content until we see the bodies and bury them ourselves."