Ten-year-old Khaled lives in a refugee camp in the countryside of Idlib, Syria. He has wide gray eyes and looks serious in front of the camera, but his friends and caregivers call him the "head of mischief."

Khaled lost his father five years ago when Islamic State militants abducted him in Idlib. That was the last time Khaled saw his father.

"Khaled's father got out from the house heading to Friday prayers, then disappeared. We searched everywhere for him. Later we learned that militants from IS had taken him, and he just disappeared," Khaled's mother, who did not want to be named, told VOA.

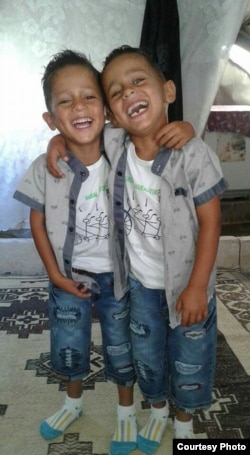

Khaled, his mother and 6-year-old twin brothers moved several times from one refugee camp to another as the Syrian government's warplanes kept striking camps in the area.They finally settled in the Uthman ibn Affan camp for orphans and refugees, where they are currently living.

"One day, Syrian government jets attacked our village. We survived," Khaled's mother said, recalling the horror that she and her children experienced.

Khaled is only one among thousands of children who have lost their parents to the war in Syria.

Syrian activist Omar Omar, who arranges entertainment for children living in refugee camps in Idlib's countryside, told VOA that the organization he works for is caring for more than 6,000 children in the area who have lost one or both parents.

"Some orphans are living with family members, like grandparents, uncles and aunts. Some are separated from their entire families, and they are supported by humanitarian organizations," Omar said.

His is just one organization caring for 6,000 children in one area. The total number of children who lost their parents could be in tens of thousands of children.

Perpetual war

The war in Syria broke out in 2011, and within a couple of years it had resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, according to estimates from opposition activist groups. But IS's emergence in 2013, after a split with what was then known as the al-Nusra Front, an al-Qaida affiliated group, further increased the suffering of ordinary people in the country. IS engaged in clashes with rebels first in Idlib and later expanded to other areas of the country, including Raqqa in the east, which became the IS de facto capital.

Since then, civilian casualties have soared. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a Britain-based monitoring group, said that as of March 2018, more than 510,000 had been killed in the war. A lot of those killed left behind children and families.

In a 2017 study published by Save the Children, a global nonprofit organization working for children's well-being, about 77 percent of adults told researchers that they knew of children who had lost one or both parents in the Syrian civil war.

Eighteen percent said they knew of children who were "living alone with no choice but to fend for themselves with little community or institutional support. Many have to work in farms or in shops, steal or beg on the streets, or join armed groups to get by," the report said. Some have had to undertake grownup responsibilities and become breadwinners for their families.

The report did not have an actual figure for the total number of orphaned children in the country.

Impact on education

According to Save the Children, more than 4,000 attacks have taken place on schools in Syria since the war broke out, which has seriously affected children's education. The organization warned that if measures were not taken, the interruption in education could have serious implications for Syria's postwar society.

The impact of being deprived of education is worse on orphaned children, because they lack the parental guidance that is needed.

Manar Qarra, general manager of the Selam Orphanage in Gaziantep, Turkey, told VOA that education is a key priority in rehabilitating orphans so that they can gain confidence and depend on themselves in the absence of one or both parents.

But she says that's not enough.

"We also focus on developing children's skills and enabling the children to discover themselves and plan for their futures," Qarra said.

Qarra added that children who have been out of school for years cannot simply go back to school, especially when there are psychological problems that could prevent them from succeeding in their studies. She said remedial instruction and therapy may be needed.

The oldest girl in Qarra's orphanage is Shahira Qaddour, 21, who came to the orphanage five years ago, along with her five younger sisters, from Homs governorate in central Syria.

Shahira and her sisters lost both of their parents.Syrian government forces killed her father. Her mother and a toddler sister were also killed in an airstrike that hit their house. Shahira and the remaining sisters miraculously survived the attack, and activists helped the girls come to Selam Orphanage.

At the orphanage, Shahira loves taking pictures and aspires to work as a photographer one day. Selam Orphanage uses many of the pictures she takes on its social media pages and website.

Exploitation concerns

Activists like Qarra are concerned that children who lost their caregivers in Syria are at risk of being forced into labor, marriage or service in armed groups.

"The orphan who comes to our center is a war orphan. The child not only suffers from the loss of a parent but also homelessness, fear and deprivation," she said.

Qarra added that traumatized mothers, who experienced abuse and sexual harassment in the past, should not be ignored by aid groups, because their emotional breakdowns and reactions could directly affect their children.

Qarra said that children affected by the war in Syria carry hidden wounds that go beyond physical loss, and with no end in sight to the conflict, they cannot regain a sense of normalcy.