The U.S. naval mission in the South China Sea that aroused angry protests from Beijing was intended to show clearly that the United States will exercise the right of naval passage near the artificial islands China is building in those disputed waters, analysts and U.S. officials said Tuesday.

China contends it can order warships such as the USS Lassen, the destroyer that sailed near Subi Reef in the Spratly archipelago, not to enter territorial waters extending 12 nautical miles (20 kilometers) from the islands it has occupied.

U.S. military officials say there will be more American naval operations in the South China Sea in the future.

The United States noted that the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea does not prohibit military vessels from territorial waters if they are operate under freely accepted freedom-of-navigation principles, as the U.S. vessel did this week, and that the South China Sea incident did not depart from those norms.

In a comparable situation just two months ago, there was no U.S. protest when China sent five warships through the Aleutian Islands chain extending from Alaska, at a time when President Barack Obama was presiding over an international conference in the same state.

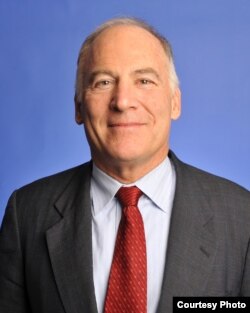

"There was no protest," maritime law expert John Oliver told VOA, "because the United States viewed that a right-of-transit passage" by the Chinese. China's condemnation of what it called a "deliberate provocation" by the U.S. was "overreaction," he added.

Oliver said the angry words from Beijing appeared to be an attempt to pressure the United States as well as Vietnam and the Philippines, who also have territorial claims in the South China Sea. He said China appeared to be telling its neighbors, "We're going to posture if you do something we don't like, and maybe even rattle our sabers a little bit, and hope that you back down."

Oliver, an adjunct professor at the Georgetown University Law Center, also is a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Coast Guard, but he spoke with VOA purely in a personal capacity. He is a veteran of 30 years of naval service, both at sea and as a judge advocate in the military justice system.

Recalling a tense Cold War standoff between American and Soviet naval forces in the Black Sea in 1988, Oliver said that resulted in an agreement between the two superpowers guaranteeing the right of warships to pass peacefully through territorial waters. Formalized in the Jackson Hole Agreement of 1989, that recognition of the right of innocent passage has become accepted worldwide. Oliver said he hoped a similar approach could be applied to the current South China Sea dispute, which he said was an analogous situation.

"Speaking as an international attorney and someone who wants to see peace in the region" of the South China Sea, Oliver said, "it seems to me the solution is an international tribunal."

Retired U.S. Admiral David Titley, now a university professor and policy analyst for the Center for a New American Security, said he hoped the calm U.S. reaction to the Chinese warships' passage through the Bering Sea near Alaska could soften China's aggressive policies in the South China Sea region.

"This is how mature superpowers operate," Titley said. "You don't go to general quarters [head to battle stations] every time there's a ship operating legally."

Apart from the question of whether foreign vessels can pass through a nation's territorial waters without prior permission, Oliver and others noted that the reef the U.S. warship approached Tuesday was a low-tide elevation — completely submerged at high tide — until China began a massive dredging operation to create an artificial island there.

The Convention on the Law of the Sea, which China ratified in 1996, excludes territorial waters protection from artificial islands, offering instead a 500-meter safety zone around their shores. China contends its activities around the Subi reef are a "reclamation" effort, not an artificial island.