When the Pilgrims set sail for America, southeastern New England was populated by a number of tribes, among them, the Wampanoags, Narragansetts and the Pequot, all of whom had established territories, as well as political and trade relations with one another.

But it would be the Wampanoags with whom the Pilgrims first established relations; the Pilgrims chose to settle the Wampanoag village of Patuxet, which they found abandoned. They would later learn that all of the villagers had died in recent epidemic.

It would be many weeks before the Pilgrims met any Wampanoag face to face. The Natives watched the newcomers from a cautious distance. This wasn’t their first encounter with Europeans: Spain had explored and mapped New England a century earlier. France had established a colony in Maine in 1604, and the English and Dutch had been trading with Indians along the New England coast for decades.

Not all these Europeans had good intentions.

“Sometimes Europeans would engage in battle with the Natives,” said David Weeden, historic preservation officer for the Mashpee Wampanoag Nation, which, along with the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), are the only federally recognized tribes in the state of Massachusetts today.

“Sometimes they took Natives as hostages or slaves,” Weeden told VOA. “And they brought diseases.”

He was referring to an as-yet-unidentified epidemic that ravaged what is now known as New England from 1616 to 1619. Historians and epidemiologists estimate that coastal tribes lost anywhere from 50% to 90% of their populations.

Tribal structure

At the beginning of the 17th century, Weeden said, nearly 70 Wampanoag villages dotted southeastern New England, with a combined population of about 12,000 citizens.

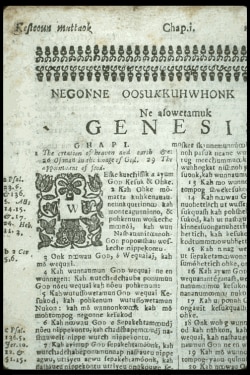

Like most Native peoples, the Wampanoag had no written language; they passed down their history orally. Today, much of what is known about them comes from Pilgrim records and accounts, but Weeden cautions against relying on those too heavily.

“Not all of our words have correlations in English. The Pilgrims were interpreting what they observed and what they were being told. But they were reading everything in a Christian context,” he said.

Each Wampanoag tribe had a sachem or leader. Collectively, these sachems answered and paid tribute to the Wampanoag Massasoit, a title meaning paramount leader. In 1620, that leader was Ousamiquin, a Pokanoket Wampanoag, based near present-day Bristol, Rhode Island.

The Wampanoag did not live in a vacuum. They were part of a greater landscape of tribes — among them the Pequot, Mohegan, Narragansett and Nipmuc — with whom they traded and shared information.

The Nauset tribe of Cape Cod would have alerted the Wampanoag to the Mayflower’s arrival at the tip of Cape Code just weeks before, likely complaining about how the Englishmen had plundered Nauset food and supplies and disturbed graves. Mayflower passenger Edward Winslow would later admit to the deed.

“In the houses, we found wooden bowls, trays and dishes, earthen pots, handbaskets made of crab shells,” Winslow wrote in “Mourt's Relation,” a history of the Pilgrims’ exploration and settlement.

"Some of the best things we took away with us,” he wrote.

Now, with the Mayflower landed, it was clear to the Wampanoag that the foreigners had no intention of leaving any time soon. Within a few days, work parties began constructing buildings on Patuxet’s ruins.

Evidence of the epidemic was everywhere. Pilgrim leader William Bradford would later write in a two-volume “History of Plymouth” that many victims of the “late great mortality” were not able to bury one another: “Their skulls and bones were found in many places lying still above the ground where their houses and dwellings had been.”

Weeden said the Wampanoag were shocked that the English would take up residence in a place associated with so much suffering and death. Wampanoag would have left it undisturbed.

The Wampanoag kept their distance through the winter. Sometimes, as Pilgrim leader William Bradford wrote later in his two-volume “History of Plymouth,” the Pilgrims spotted smoke from distant Wampanoag campfires.

“All this while the Indians came skulking about,” he said, “and would sometimes show themselves … but when any approached near them, they would run away.”

Then, one afternoon in mid-March, to Bradford’s astonishment, a Native man strolled into Plymouth and introduced himself in English as Samoset, a visiting leader from a tribe in Maine.

The Pilgrims fed him, asked him many questions, gave him some gifts, and sent him on his way.

A week later, he returned, bringing with him Tisquantum (Squanto), whose English was even better than his own. They carried a message: Ousamiquin, who was nearby with several dozen warriors, wanted to parley.

By the end of the day, the parties had negotiated a peace agreement promising, among other things, not to harm one another and to support each other in the event of an outside attack.

Squanto remained with the Pilgrims as an interpreter and “a special instrument sent of God for their good,” as Bradford later described him. Squanto taught the newcomers “how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities.”

Motives for helping

Generations of historians have painted the Wampanoag — and Squanto in particular — as friendly Native Americans who reached out to the Pilgrims out of the goodness of their hearts.

That’s partly true, Weeden said.

“The Wampanoag people had been watching the English for a while and compared them to little children who didn't know their way around,” he said. “And because they had women and children with them, the Wampanoag looked on them with empathy and compassion.”

But, he explained, his ancestors also had political motives for reaching out to the strangers.

“Two-thirds of the Nation was wiped out from disease,” Weeden said. This left them vulnerable to their political, economic and military enemies — the Narragansett, who, because they were based on the western side of the Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, had fewer dealings with Europeans and were untouched by the epidemic.

The alliance would stand for the next 50 years.

“But [the relationship] wasn’t all ‘Kumbaya,’” Weeden said, referring to a 19th-century folk song today associated with naïve do-gooders.

“Whether it was through the propagation of the gospel or by land ownership,” he said, “the English tried to extinguish us.”

In 1675, 54 years after signing a peace treaty with the Pilgrims of Plymouth, the Wampanoag rose in a last-ditch effort to resist colonialism and were defeated.

Some Wampanoag bands died out completely; many were sent to foreign plantations as slaves. Still others, mostly Christian converts, survived. Today, generations later, their descendants are merged into two main groups, the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe on Cape Cod and the Wampanoag of Gay Head (Aquinnah), Martha’s Vineyard.