For decades, the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians in Montana have lived in a state of neitherness — neither completely Native American nor non-Native American. But last month, its 5,400 members received a gift they have waited decades for -- federal recognition.

The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians Restoration Act, sponsored by Senators Jon Tester and Steve Daines and Representative Greg Giaforte, was tucked into the National Defense Authorization Act, which U.S. President Donald Trump signed into law on December 20.

The bill gives the tribe the same benefits afforded treaty tribes and other recognized tribes the right to self-govern and a small land base of 200 acres, which the tribe must purchase and which will be held in trust by the government. Tribe members will be eligible for assistance with education, health care, social services, law enforcement, and other programs.

“It might not seem like a big deal to the folks who aren’t impacted,” Tester told reporters during a December 17 conference call, “but the truth is that this is going to allow the Little Shell to really move forward in a way that they’ve been trying to do for 150 years.”

Little Shell Tribe member Rylee Mitchell, a resident of Great Falls, Montana, is in her last year of high school and looking forward to attending college.

“I can apply for scholarships now because there are thousands of them open,” she said. “But without being federally recognized, I could apply for only eight.”

The Mitchell family will now be able to access health care through the Indian Health Service, a federal agency that provides health care services to Native Americans and Alaska Natives.

Most importantly, federal recognition will give tribe members a sense of legitimacy they’ve been denied for more than a century.

“The other tribes in Montana, they have their own high schools and their own sports programs,” said Rylee’s mother Julie Mitchell. “They get to keep their language and their traditions and their culture together.

Nobody really understands the Little Shells’ history, she said, or how they ended up landless.

It’s a complex, spotty and much-disputed history: The Little Shell Band is descended from the Pembina, one of dozens of bands of Chippewa, (Ojibwe) who followed the buffalo from the western Great Lakes across the Plains states. They eventually settled along the Red River dividing Minnesota and North Dakota and flowing north into Canada.

They were what Montana historian Nicholas Vrooman referred to as a mixed-culture recombinant group — some having pure Chippewa ancestry, but the majority having mixed Ojibwe, Cree, Assiniboine, European and Metis heritage. Despite their varied ancestry, they were a cohesive group with its own cultural identity.

The mid-19th Century brought great change to the Chippewa. The fur trade, which had previously sustained them, now declined. Buffalo were quickly disappearing from the Plains. White settlers and the railroad were encroaching, and the U.S. government was working furiously to push Native Americans onto reservations or across the border into Canada.

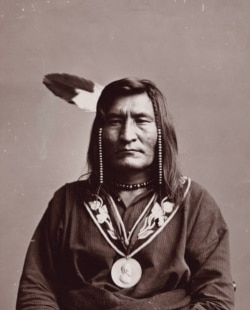

The turning point for the Little Shell Pembina came in 1892, when Chief Little Shell, the third of a succession of leaders by the same name, refused to sign the so-called “Ten Cent” treaty ceding nearly 10 million acres (4 million hectares) of prime farm land in the Red River Valley for 10 cents an acre and omitting many Little Shell families from the rolls.

Little Shell and most of his followers migrated into Montana, where they scattered, living in poverty and squalor on the fringes of settler towns “like they didn’t even exist,” said Little Shell Tribe member, historian and genealogist Brenda Snider.

“We never felt welcome by any of the other Montana tribes,” Snider said. “It was like we weren’t real Indians but ‘wannabe’ Indians. And to the white people, we were just ‘trashy half-breeds.'”

Those attitudes, said Snider, persisted well into the present day.

Though scattered, Snider said the Little Shell managed to maintain their sense of unity and political cohesion.

“We call it the ‘Moccasin Telegraph,’” quipped Snider. “The families kept in touch with each other.”

They never stopped looking for federal recognition and a land base to call their own. Tribes can be recognized either through an act of Congress or by petitioning the Interior Department (DOI) and meeting seven strict criteria proving historical, genealogical, and anthropological proof they have existed as a continuous governing body.

The Little Shell pursued both tracks. With support from the Native American Rights Fund, they submitted tens of thousands of documents to DOI, but were ultimately turned down.

It was a separate congressional effort led by U.S. Senators Steve Daines and Jon Tester and U.S. Representative Greg Gianforte that finally paid off.

Snider said the tribe must still submit an updated list of its members. It has not yet decided where their 200-acre reservation will be located.

“The government will sit together with our chairman and find a piece of available federal land in Montana. One that has the right of access and water,” she said, chuckling, “not just some piece along Rattlesnake River.”

Two hundred acres is hardly enough land to accommodate an entire tribe, but it’s enough to house tribal offices and a cultural center.

“I’m hoping we can educate more of our people and get some job training done,” she said.