When someone goes missing in Indian Country in the United States, chances are the family won’t turn to the police for help but to a growing community of female volunteers who work day and night to spread the word about the missing, organize scouting parties and fight to keep cold cases alive. VOA spoke with three women from separate tribes who are doing their part to safeguard their sisters and bring justice to families in mourning.

Many hats

Geneva Hadley, a member of the Comanche Nation in Oklahoma, had never heard of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Movement (MMIW) until 2016, when she and a group of fellow tribe members traveled to North Dakota to join the Standing Rock pipeline protests. She met a group there called “No More Stolen Sisters.”

“We started talking to them, and one of the first things they told us was, ‘Watch your surroundings. Don’t go anywhere alone,’” said Hadley. The warning referenced the growing connection between transient oil workers in North Dakota’s oil fields and the trafficking and murder of Native American women.

After the shocking murder in 2017 of Savanna Greywind, a pregnant member of North Dakota's Spirit Lake Nation whose unborn baby was cut from her womb and kidnapped, Hadley was spurred into action. She founded Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women of Oklahoma Southwest Chapter, a Facebook page devoted to raising public awareness about MMIW.

“I’ll comb Facebook for notices about missing people, and if it is in our area, I will call the family and see if they have reported it or if they have a search party going,” said Hadley. “And if they don’t, then we’ll just go out and walk the streets, talk to people, hand out flyers, and coordinate with other MMIW chapters.”

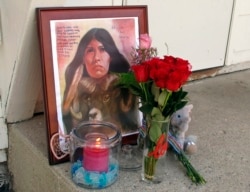

At first, she said she felt as if her efforts went unnoticed. But on July 28, 2019, her group staged the first in a series of vigils, each honoring a murdered or missing Comanche woman.

“That event seemed to open the doors, and since then we have been doing podcasts and interviews with the news, and we’ve been invited to speak at conferences,” Hadley said.

She’s been successful in getting her tribe to pay for billboards about the missing to be erected the city of Lawton as well as wraps on local buses to feature faces of MMIW.

Recently, she participated in a private meeting between Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders and more than four dozen MMIW activists and family members, eliciting a promise from Sanders that if he is elected president, he will appoint an attorney general who will ensure justice for slain native victims and their survivors.

‘Care for our own’

Theresa Small, disaster & emergency services coordinator for the Northern Cheyenne Nation in southeastern Montana, says most of the time, families who are reluctant to speak with police will call on her for help.

“I’ll tell them that the first step is to go report it to the police so we can get the information into the National Crime Information Center database,” she said. “Sometimes, I even have to walk them through it, holding their hand, because a lot of people just don’t feel valuable enough to call on police. Like maybe they think they’re being judged, or maybe it’s too soon to even report someone missing.”

One of Small’s jobs is to organize search parties to comb the 1,800-square-kilometer reservation.

“I go straight to the chair lady (tribal president Rynalea Whiteman Pena) and ask her if she can help, because it’s easier to do my job with resources in place like drones and ETVs and trucks and manpower that we, as a volunteer search group, we haven’t been able to get,” Small said. “So, she will put out a memo to all the programs and say, ‘It’s at your discretion.’”

In December 2018, after a 14-year-old tribe member disappeared, Pena gave tribal employees permission to leave work early and join a volunteer search party that Small organized.

“For far too long, we have relied on the police to basically police us, to set down laws and enforce them,” said Small. “But the way things are now, we have to learn to police ourselves and care for our own.”

‘It’s going to happen again’

Lissa Yellowbird-Chase, an enrolled member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, founded the Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota, a citizens group that organizes searches for the missing and murder victims.

“I’ve been doing this since 2011,” the former welder with a degree in law enforcement, said. “Last December I left my job, and I’ve been just basically using my so-called retirement funds — or whatever is left of them — to just keep doing what I’m doing full time.”

She has an uncanny ability to find bodies — at least 15 so far. “It’s really hard to explain to a non-Native how I do it,” she said. “For us to find our people, we have to be reconnected not only to our ways but to Mother Earth. I have acclimated myself and connected myself spiritually with the land.”

That means talking to trees, talking to animals, “because we’re all connected; we’re all related,” and taking notice of the slightest deviations in the natural landscape.

That understanding of nature, she said, gives her an advantage. She points to the example of a case of a missing woman that stymied police.

“Local law enforcement put in over 1,000 man-hours looking for her,” Yellowbird-Chase said. “We found her in only half an hour.”

Her reputation has spread beyond just her tribe, and now she gets calls from as far away as Minnesota.

“I’m overwhelmed. I try to do my daily cases and try to foster other people to initiate their own search-and-rescue groups and educate them about what worked for me,” she said. After a long pause she added, “'Cause it’s going to happen again, and there are people out there that need to be found.”