With tensions between Russia and Ukraine ratcheting up, some former diplomats and Kremlin watchers are debating the effectiveness of any sanctions imposed on Moscow should it invade its neighbor to the west.

Britain's former ambassador to Russia, Tony Brenton, has long doubted the efficacy of sanctions, saying they "don't work on Russia."

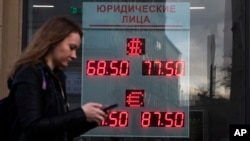

Brenton has argued "Russia just becomes even more obdurate." And some critics of sanctions say Russia has been readying itself to withstand more Western penalties — from cutting back using dollars to boosting foreign currency reserves and trimming budgets. Russia has a current account surplus of seven percent of GDP and $638 billion in foreign reserves.

Russian business has also become adept at import substitution and its major banks are well-funded, they say.

Others think sanctions can work if they are sufficiently ruthless, adding that the Kremlin needs to be left in no doubt how biting they will be this time around.

U.S. President Joe Biden and European leaders hope that by raising the price of war for Russia, President Vladimir Putin will be deterred, and they have maintained a steady drumbeat of warnings in recent weeks, saying a further Russian invasion of Ukraine will trigger the harshest economic sanctions ever seen.

New sanctions would also target Russian companies and oligarchs close to the Russian president, Biden and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson warned this week.

"The individuals we have identified are in or near the inner circles of the Kremlin and play a role in government decision making or are at a minimum, complicit in the Kremlin's destabilizing behavior," White House spokesperson Jen Psaki told reporters in Washington.

Russian officials have been dismissive of the warnings. "It's not often you see or hear such direct threats to attack business," Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said at a news conference this week in the Russian capital.

And Peskov promised a significant response that would hurt Western businesses if Russia is sanctioned again. "An attack by a given country on Russian business implies retaliatory measures, and these measures will be formulated based on our interests, if necessary," he added.

The diplomatic exchanges over sanctions come amid escalating tensions over Russia's troop buildup on the border with Ukraine. Russia's troop presence marks the biggest military buildup Europe has seen since the end of the Cold War.

The United States accuses Russia of preparing an invasion, which Moscow has repeatedly denied, accusing Western powers of causing alarm.

There has long been a debate about the effectiveness of sanctions, including among some who were in Biden's inner foreign policy circle before joining the administration.

Victoria Nuland, now a top official at the State Department, questioned more than a year ago whether sanctions actually work and argued their use against Moscow needed to be rethought. In Foreign Affairs magazine, she wrote, "U.S. and allied sanctions, although initially painful, have grown leaky or impotent with overuse and no longer impress the Kremlin."

U.S. officials last year said Biden intended to review the sanctions already imposed on Russia. Some officials say the aim is to readjust the sanctions to increase their immediate impact, as part of an effort to fashion a more rounded and consistent Western strategy toward Russia — one that aligns military, economic, energy, diplomatic and communications policies. Whether an actual review ever took place or whether events overtook a review is not clear.

Kremlin officials have long downplayed the impact of the Western sanctions that began to be imposed in retaliation for Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea, apparently hoping to persuade Western governments to abandon them on the grounds that they don't work.

Aside from sanctions for the Crimea annexation and seizure of part of Ukraine's Donbass region, Western governments have implemented penalties in response to malicious cyber activities they blame on the Kremlin. Sanctions also have been imposed for alleged human rights abuses and for the March 2018 nerve agent poisoning in Britain of former Russian military intelligence officer Sergei Skripal and his daughter.

Some sanctions have been broad economic ones. Others have targeted individuals.

Part of Moscow's line has been that sanctions are hurting Western countries more than Russia, a position often echoed and amplified by business interests in the West. While the Kremlin has downplayed the significance of the penalties, it also has railed against them and maintained that they should be lifted, saying they amount to "interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state."

That may suggest sanctions have been more troublesome for Russia than the Kremlin is willing to admit, according to David Kramer, a former assistant secretary of state in the administration of President George W. Bush. "If you look at all the efforts and time and energy the Kremlin has spent on trying to get sanctions lifted, then that would indicate that the Russians feel they have had an impact," he told VOA recently.

Kramer suspects Russia might have been tempted to encroach further into Ukraine in 2014 and 2015 had the West not imposed sanctions. This time round, though, he's worried that the sanctions being contemplated won't in the end be tough enough.

"I am worried that there is not complete agreement on the range of sanctions," he told VOA. "It's difficult to get agreement among 27 EU member states, and that's why, while U.S.-EU unity is preferable, it's sometimes necessary for the U.S., possibly with the UK and Canada, to go ahead on its own rather than settle for the lowest common denominator," he said.

"U.S. sanctions are extraterritorial in nature and can have significant impact, especially if we target their banking and energy sectors, as well as Putin and the circle immediately around him, as proposed in recent congressional legislation," he added.

Some Kremlin watchers question whether targeting high-profile individuals, from oligarchs to government officials, has much of an effect aside from symbolism, arguing sanctioned individuals are compensated by the Kremlin for their losses and are not going to lobby Putin to modify or alter his policies as their status and wealth depend on their loyalty to him.

They say sanctions need to be broad-based and impact key companies in Russia's important energy, defense and financial sectors. Edward Fishman, a former member of the U.S. secretary of state's policy planning staff, has long maintained the penalties imposed on Putin's Russia in the past were watered down because U.S. allies were reluctant to suffer blowback economic costs and wanted to reduce harm to ordinary Russians.

"To change Putin's behavior, you need to ratchet up sanctions on companies in the energy, defense and financial sectors — that would more likely force the Kremlin to shift its calculus," he told VOA recently. "The scale of sanctions has to be much greater to prompt a change in behavior."