Afghanistan's government is in advanced stages of negotiations with several U.S. companies interested in becoming involved with the country's coal industry, a first step toward wider American investment in Afghanistan's potentially lucrative industrial mining sector.

The negotiations - confirmed to VOA by a senior Afghan diplomat and the owners of two consulting firms that specialize in the extractive industries, all of whom are involved in the talks - are in line with a push by President Donald Trump for greater U.S. economic involvement in Afghanistan, where the United States is entering its 17th year of war.

Trump has complained the U.S. is not profiting from the conflict, leaving China to take the lead in exploring the country's natural resources.

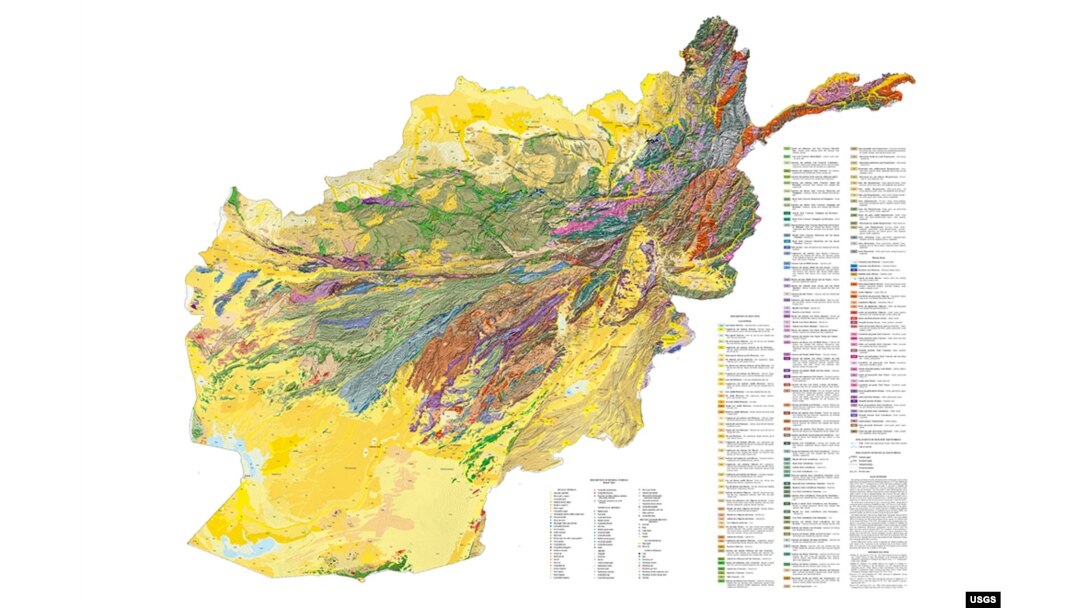

Specifically, Trump has had his eye on Afghanistan's vast supply of untapped mineral deposits, which the U.S. Geological Survey estimated in 2010 were worth as much as $1 trillion.

Though coal is not among the country's most valuable natural resources, U.S. companies involved in such a deal would be well-placed to take advantage of future opportunities involving copper, gold, lithium and rare earth elements.

Map: Geologic and mineral resources of Afghanistan. Click image to download full map (PDF, 26 MB)

For the Afghan government, which is almost completely reliant on foreign aid, the agreement would provide both a measure of self-sufficiency and a better chance of long-term U.S. commitment.

"This is a way to bind the two countries long-term," said the Afghan diplomat helping negotiate the deal, speaking on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to publicly disclose the agreement.

As envisioned, the Afghan government would invite companies to bring mining expertise, equipment, logistics and security to Afghanistan to help extract coal and fuel what would be the country's only large-scale, coal-fired power plant, hopefully within one to two years.

Seventy percent of Afghans do not have access to reliable electricity, and the country is largely dependent on often-interrupted supplies of imported power from neighboring countries.

That shortage makes domestically fueled power plants a possible game-changer, said Mohsin Amin, an Afghan energy policy analyst. "There is a huge market in almost all the provinces for electricity," he said. "Boosting the power sector would be very, very beneficial for Afghanistan."

Obstacles

Mining in Afghanistan faces formidable challenges. The country lacks much of the basic infrastructure needed to extract, process, and deliver minerals to global markets. It is also one of the world's most dangerous and corrupt nations.

Starting with a coal mining deal is an attempt to conquer those obstacles. Since coal must be extracted in large quantities, it is more difficult for militants to loot than other more valuable resources, such as gold. It is also less vulnerable to claims by Taliban insurgents that the Afghan government is colluding with foreign invaders to plunder the country's natural wealth.

"We are cautious about this argument," said the Afghan official. "That's why we have chosen coal to begin with. If you win the confidence of the people when it comes to coal, then you can move on to other resources."

Coal has long been mined in Afghanistan, especially in the north and west of the country. Three to four million tons of coal, valued at $300 million to $400 million, are already extracted each year, according to a 2017 estimate by the U.S. Institute for Peace. By comparison, U.S. coal production in 2016 was about 700 million tons.

But the bulk of Afghanistan's mining is off the books and illegal - overseen by warlords, politicians, or other politically connected individuals. As a result, very few taxes from the mining sector go to the cash-strapped Afghan government.

"Afghanistan is not short of people digging stuff out of the ground," said Stephen Carter with Global Witness, a watchdog group that monitors natural resources exploitation. "The problem is that when the extraction does happen it doesn't benefit the government."

Global Witness says it is not necessarily against a proposed coal mining deal. But it would oppose any major new contracts, especially those involving more valuable resources, until Kabul establishes a structure that would provide greater transparency in the mining sector.

Since 2009, the U.S. has poured nearly $500 million into efforts to clean up the regulatory structure around Afghanistan's extractive industries, according to a 2016 report by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR). But that effort has seen "limited progress," said the report, citing concerns about incompetence and widespread corruption in the country's mining ministry.

"The question is really around the transparency of the production, who the partners are, and who is benefiting," said Carter. "The stakes are very high for the Afghan people, because these are resources that you can only dig out of the ground once, and which are desperately needed for development."

Security concerns

Afghanistan's mining sector is also held back by conflict. Since many deposits are in Taliban-held areas, some companies have paid off insurgents for protection, according to Global Witness. Mining is the biggest source of revenue for the Taliban, after narcotics.

However, unlike Afghanistan's other natural resources, companies can more easily extract coal from areas not held by the Taliban, since coal deposits are scattered throughout the country.

Map: Location of coal deposits and coal mines in Afghanistan

But coal mines are still vulnerable. Last month, insurgents torched two coal trucks and took the drivers hostage in the north-central province of Samangan. It is reportedly the third time in a month the coal mine had been attacked.

The Taliban in 2016 offered protection to a large, Chinese-backed copper mine (such projects improve the economy and are in the "interest of Islam," they said).

But it's not certain whether the armed group would apply the same standards to an operation linked to the U.S., a country it's been at war with since 2001. It's also not clear how groups like Islamic State would respond.

Security for the operation would likely be Afghan-led, but would probably also include foreign contractors, according to one Afghan official.

Kabul says it has reached a preliminary agreement with at least some of the companies that would provide logistics and security for the project. U.S. coal companies are among those involved in the talks.

But according to two officials involved in the negotiations, the deal hasn't been finalized and is moving slowly, in large part because of delays in the confirmation of Afghanistan's recently appointed mining minister, Nargis Nehan, who is still in an acting role.

Afghanistan is also in the process of a slow-moving review of its mineral law, and has frozen nearly all contracts and bids with Western companies.

A boost for US coal?

But why would U.S. coal companies want to do business in a war zone?

"The number one thing they'd get out of something like this is survival," says Andy Roberts, a consultant who focuses on emerging coal markets at Wood Mackenzie.

Since the U.S. coal market is in a prolonged slump and fresh domestic demand is unlikely, Roberts says many companies are looking to the developing world for growth opportunities.

In Afghanistan, those opportunities include not only coal, but also more valuable resources, such as lithium or rare earths.

"It at least opens the door a crack toward capturing value in other commodities," he says. "They'll have in-country expertise having done this. They'll know people. They'll know the workforce. They'll understand the problems better and be better positioned."

Additionally, much of the equipment used in coal surface mines - such as trucks, bulldozers, and pipes - could be used at any surface mine, he says, making it easier if the companies eventually wanted to focus on other deposits.

"I see it as an important, West Virginia-led initiative," said one person involved in the negotiations. "Instead of trying to recreate coal mining jobs in West Virginia, why not export your technical expertise to other markets?"

The Trump factor

But any U.S. effort to extract Afghanistan's natural resources is politically tricky, not least of all because of Trump.

For years Trump has lamented that other countries profit from Afghanistan's natural resources, while the U.S. spends billions fighting to secure it.

"China is taking out all the minerals. And here we are fighting...and we get nothing out of it," Trump said in an interview in December 2015.

(It's an overstatement to say China is taking "all" the minerals" - though Beijing in 2007 signed a $3 billion deal to lease Afghanistan's Mes Aynak copper mine, the project has been stalled over contract disagreements, instability, and the possible impact on a 5,000-year-old Buddhist archaeological site that lies directly above the copper deposit.)

The ruins of an ancient temple in Mes Aynak, Logar province, Afghanistan are seen in this Feb. 14, 2015 file. The copper lying beneath the ancient Buddhist ruins is one of the world's largest untapped deposits.

As recently as August, Trump reportedly complained that U.S. officials haven't acted quickly enough to help American businesses acquire rights to Afghan minerals.

Many critics are uncomfortable with explicitly linking decisions about U.S. military intervention to the exploitation of natural resources.

Kabul, too, is sensitive to those concerns, according to Afghan officials. But the government may have more pressing worries. Amid a resurgence in Taliban attacks, Afghanistan's President Ashraf Ghani recently told "60 Minutes" that the Afghan Army wouldn't last six months without U.S. support.

Though Trump's new "conditions-based" strategy essentially commits the U.S. to Afghanistan indefinitely, many in Kabul are mindful that Trump for years slammed the U.S. war there as a "complete waste."

Given that dynamic, it will be imperative for both sides to make clear that U.S. companies have not gotten preferential treatment, warns Carter with Global Witness.

"I can see why some people might take the view that America deserves some gratitude for what they've invested in Afghanistan," Carter says. "But mining concessions are not the proper currency for expressing that gratitude."

One official involved in the talks acknowledges it will be "very, very difficult" to combat those perceptions. "I think that's a really legitimate concern, and I don't know what the answer is," said the official.

The official stressed it will be important for U.S. companies to partner with local Afghans, and secure buy-in from the local community. "Otherwise, you could end up in a situation where the local population rises up and physically threatens the mining operation."

However, if the project can successfully navigate the risks of corruption and conflict, backers say there are few foreign investment opportunities that could provide Afghans with as many practical, long-term benefits.

"The Afghan people will get electricity from it. The Afghan government will get revenue and jobs from it. And U.S. companies will...also profit, of course," says the Afghan official. "It's a win-win situation."