It’s hard to miss Samira Chaouachi—she’s a regular face on local TV. She is sought after too, by foreign media this election season, as spokesperson for jailed presidential candidate Nabil Karoui’s Heart of Tunisia party.

Parliamentary election candidate Yeah Loumi, right, of the Kalb Tounes (The heart of Tunisia) party, talks with man in a cafe outside Tunis, Oct.1, 2019.

Chaouachi also is running in Sunday’s legislative polls, heading the party’s list for a key Tunis district.

“It has many working class neighborhoods, some of the poorest populations,” she says, laying out a campaign platform to grow jobs and boost tourism in the city’s ancient Medina.

She pauses to chat with colleagues strategizing at a recent party meeting in the capital. Her cell phones beep regularly. This snapshot of female power politics may be rare elsewhere Arab world, but not in post-revolution Tunisia.

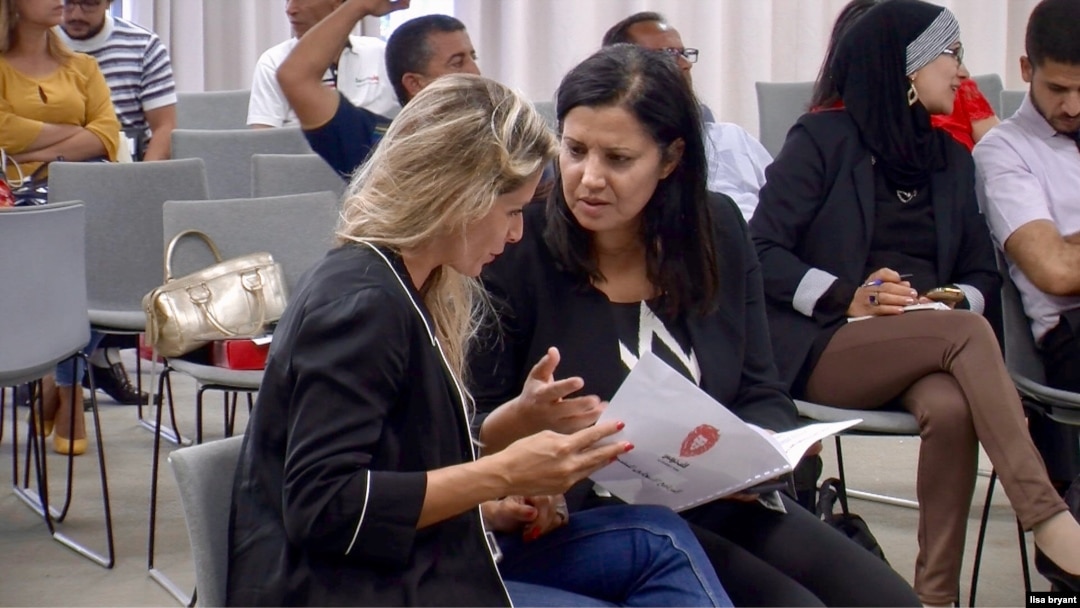

Sana Ghenima heads an association trying to get Tunisian women more politically active. (L. Bryant/VOA)

“After 2011, we women gained lot,” says Sana Ghenima, president of the Women and Leadership Association in Tunisia, a group working to get women active in political life. “Parity of course, as well as full equality and full citizenship.”

Key test

Sunday’s vote will be a key test of whether women can consolidate these advances. Several factors however, including less stringent parity rules for the legislature and potentially low female turnout, make this election more challenging.

Women also are worried that a possible win by conservative candidate Kais Saied in the October 13 presidential runoff may set back key legislation for equal inheritance. Chaouachi says her candidate, Karoui, supports the equal inheritance bill.

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5

Tunisian Women Hope to Secure Gender Parity Gains in Legislative Vote

Tunisian women have long enjoyed far broader rights than many of their Arab counterparts in areas ranging from education to marriage, advances initially imposed on a conservative society by the country’s Western-educated, post-independence leader, Habib Bourguiba.

Recent years have ushered in more gains. In 2016, parliament amended local election laws, requiring parties to ensure gender parity not only in numbers, but also in ranking.

SEE ALSO: Some Young Tunisians Aren't Waiting for Politicians to DeliverThe results were stunning. Women clinched nearly half the local council seats in last year’s municipal vote. Even without the equal ranking rule, they make up one-third of Tunisia’s current parliament, compared to just 20 percent in the United States and well above their North African counterparts, according to World Bank statistics.

The capital also has its first female mayor—Souad Abderrahim, from the moderate Islamist Ennahdha party.

Gender in politics

Women lining up to vote in September's presidential election. (L. Bryant/VOA)

“I think women are going to do better than previously” in the legislative elections, said 25-year-old bank statistician Mouna Belaid, who voted for one of two female candidates running in September’s first round of presidential elections. “But I’m always optimistic about Tunisia.”

For her part, activist Ghenima believes female candidates increasingly are seen as mainstream.

“Voters are putting less emphasis on gender in recent years,” she says. “They’re just looking for someone to represent them—and women are very powerful when it comes to representing a large slice of society and real problems.”

Still some corners of Tunisia remain staunchly conservative. Leila Ben Gacem, a municipal councilor in the eastern village of Beni Khalled, recounts less-than-upbeat experiences running unsuccessfully for mayor last year.

“I met many women who said ‘a woman should not be mayor,’ and of course it was a bit of a shock for me,” she says. “I heard things like, ‘you don’t sit in a cafe with men, so there’s no way you can know what’s going on.’”

Heart of Tunisia’s Chaouachi has also faced challenges. She is no stranger to being treated as a quota—at least in the past.

“The women weren’t always the right ones for the job,” she acknowledges of earlier candidates. “But since the revolution it’s more about competence. You have to fight within your party to be a leader.”

SEE ALSO: Tunisians Vote in Presidential Elections Amid Grim Economic BackdropTough fight ahead

There are signs this next fight for parliament will be tough. Unlike the municipal elections, there is no required parity in ranking, although parties must run equal numbers of male and female candidates.

Women head just one-third of Heart of Tunisia’s party lists for the legislative vote. Chaouachi, however, says women hold number two spots in the party’s other lists, suggesting some could be voted in.

But female candidates from other parties may not fare as well. They top less than 10 percent of Ennahdha’s lists, for example.

“We are unhappy with the 10 percent,” said senior Ennahdha member Khalil Amiri, adding it was hard to persuade qualified women to run. “Hopefully in the future we’ll do better.”

Increasing female voter participation may pose another challenge. Many Tunisians of both sexes are disappointed with politicians for failing to deliver on jobs and growth. Less than half of eligible voters cast ballots in last month’s presidential election.

Activist Ghenima has been encouraging women to turn out at the polls this Sunday, but she acknowledges it has been difficult.

“They are losing hope, they are not so involved,” she says. “They don’t like to have another disappointment.”