Editor's note: Steve Herman, VOA’s Southeast Asia Bureau Chief, previously covered the Korean peninsula from Seoul. In 2013 he spent 10 days in North Korea and was able to extensively interact with officers of an elite unit of the Korean People’s Army. He viewed "The Interview" online on Thursday.

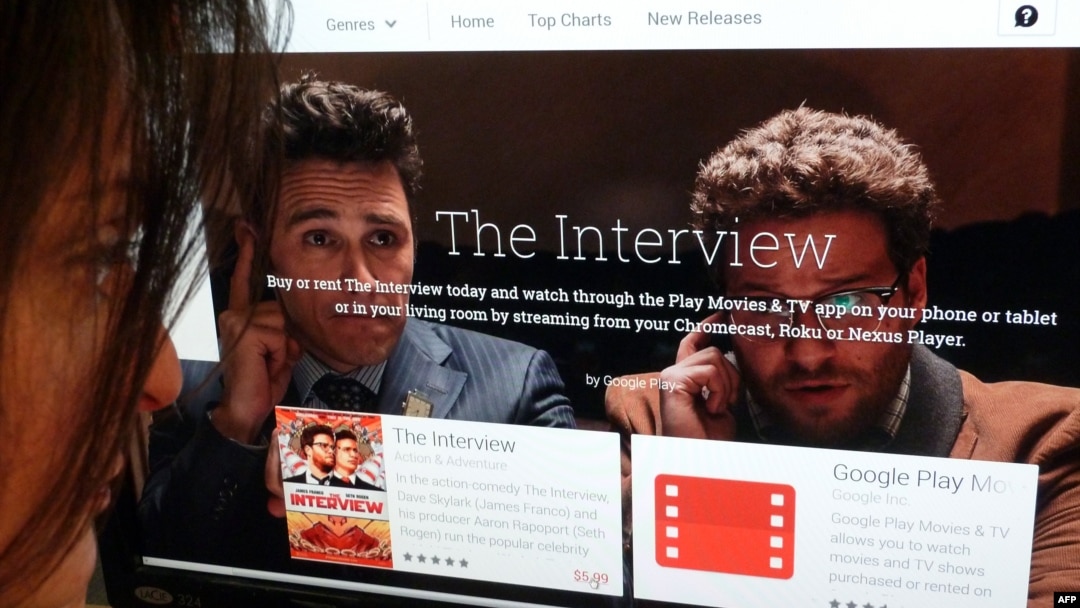

Millions of people are expected to pay $5.99 to spend 1 hour and 52 minutes of Christmas Day viewing online a controversial comedy that an already angered North Korea may come to regard as subversive.

On its surface, "The Interview," a Sony Pictures film about two journalists recruited by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency to assassinate North Korean President Kim Jong Un, could be considered a foul-mouthed ridiculous comedy, best appreciated by adolescent boys.

The French news agency AFP characterizes it as a hybrid of a "slapstick" James Bond movie and "The Hangover," about a group of young men who drink themselves into an alcoholic stupor so severe they have no recollection of the events that transpired in the aftermath.

However, Pyongyang’s pre-release protests about the comedy and the subsequent cyberattack on Sony Pictures, which the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has blamed on North Korean hackers, has propelled the film into the headlines and made it worthy of critical scrutiny due to its geopolitical ramifications.

In the story's plot, American TV chat show host Dave Skylark (played by James Franco) and producer Aaron Rapoport (Seth Rogan) score the first-ever interview with Kim Jong Un (Randall Park), "the most reclusive leader on the planet."

The CIA intervenes, convincing the duo to attempt to kill Kim by a transdermal strip of delayed-action ricin poison to rid the "dangerous and most unpredictable country on Earth" of its supreme leader.

Typical parody

Typical of a Hollywood parody, things go horribly wrong before (spoiler alert!) the Americans, allied with a comely female Korean People’s Army (KPA) officer who has betrayed her leader, shoot down Kim’s helicopter just as the dictator is about to launch nuclear missiles.

The dialogue contains references to concentration camps, famine and firing squads. The protagonists argue among themselves whether killing Kim will change anything. The assertion is that the North Korean people "must see he is not a god."

The movie's on-screen interview is broadcast live to the world – including to the North Korean people, something that would be inconceivable in the real world. It begins with soft questions along the lines of "at this time of great stress, do you do karaoke?"

Eventually, Skylark finds the courage to fire precise questions at the leader that any legitimate journalist having the opportunity to do so in real life would ask. From there, the live interview takes a dark and ultimately violent turn that leads to "the small faction in the existing leadership that wants change" to make its move, launching civil war.

The happy ending has the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea preparing for its first real election.

U.S. President Barack Obama, who has not indicated whether he has watched the movie, told reporters Wednesday during his Hawaii vacation that he is "glad it’s being released." Perhaps only a handful of those viewing the movie online will be North Koreans. Access to the Internet is extremely restricted in the reclusive country and it is questionable how many have a credit card to enable video-on-demand access.

They will not be amused

Most North Koreans (except those who defected) with whom this correspondent had conversed in Pyongyang and elsewhere appeared to sincerely believe what they read in their country’s media: The United States and its allies are looking for any opportunity to undermine their country’s socialistic system and thwart its attempts to advance, militarily and materialistically.

In a nutshell, they will not be amused.

Most likely, they will be horribly offended and outraged, as well as confused. But could this movie sow seeds of doubt and act as a catalyst for undermining the regime?

North Koreans live in a totalitarian society with a third-generation autocratic leadership where any disrespect or even ridicule of the Kim dynasty can have dire consequences.

North Koreans have no cultural context, under their state-run education system and media, for the parody of a James Franco-Seth Rogan buddy movie that goes beyond just poking fun at their country and leader. North Korea has stated release of "The Interview" would be an "act of war." It threatened "decisive and merciless countermeasures."

Kookmin University professor Andrei Lankov, who previously lived in Pyongyang, writing in The Wall Street Journal this week, explained "the members of the Kim family are godlike figures in their country, so the movie was an act of blasphemy. If such an act is left unpunished, they might reason, it sets a dangerous precedent."

There is precedent, however.

A decade ago, Hollywood made fun of then-North Korean leader Kim Jong Il in "Team America: World Police." But in the satire, in which the 270 characters are puppets, Kim Jong Il outsmarts his hapless nemesis, Hans Blix, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

At that time, Pyongyang did not have a credible missile, nuclear and cyber arsenal with which to back up any threats. This time around, North Korea "is likely to seek even more destructive ways to lash out, including through its ongoing nuclear and missile development," predicts Scott Snyder, director of U.S.-Korea Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations.

No understanding of US government

The North Korean officials this reporter has met on separate occasions in Pyongyang and Tokyo displayed no understanding of the complexities of the American system of government, with its three branches of checks and balances and the Constitution guaranteeing rights such as freedom of expression.

In North Korea, all members of the media take their cues from the state. In the United States, they assume, it is the same. Thus, the production and distribution of "The Interview" to many North Koreans will be seen if not a product of the U.S. government, something it vetted and endorsed, no matter how obviously laughable that notion is to most of the rest of the world.

What would Kim Jong Un, who is known to have access to Western media, including Hollywood movies, think of himself being portrayed as a sobbing buffoon with daddy issues bent on starting a nuclear war?

Former NBA player Dennis Rodman is the highest-profile American to have met him and perhaps the outsider with the best insight. Rodman, who has called Kim his "best friend," has been uncharacteristically subdued about "The Interview," saying this week he has no opinion about it because "it’s only a movie."

Since the inception of cinema, however, films have demonstrated their power to be more than mere entertainment.

Hollywood has been characterized as an instrument of America’s soft power, conveying its culture, political values and foreign policy.

"The Interview" is more self-aware than it might appear at first glance. Its characters observe that they manage to ignite a revolution in North Korea with "nothing more than some cameras and a question."

In a different scene, the film asks and answers another question: "What’s more destructive than a nuclear bomb? Words."