Scientists in Switzerland say they have developed a matchbox-sized device that can test for the presence of harmful bacterial activity in an infected patient in a few minutes instead of the days or even weeks current medical technology requires.

With antibiotic resistant bacterial infections on the rise, doctors say they need to be sure they are administering just the right antibiotic at the exact dosage needed to effectively and quickly treat a specific infection.

Sometimes an infection is so severe that a patient may be within hours of death unless proper treatment is given immediately.

Today, though, it takes a long time to determine that specific and crucial mix of what antibiotic to use and how much of it should be administered to a patient who may be infected with any of a countless variety of contagions.

Medical professionals must first culture the bacteria, observe its growth, and then measure the bacterial infection's response to any of a number of antibiotic treatments.

But, in cases when time is a major factor, doctors often just don’t have that luxury of using the lengthy lab work needed to help determine such specific treatment.

Past experience used to make judgment

Instead, many simply rely on their past experience and use their best judgment to select what they consider to be the most effective medication to treat their patient.

While in many cases this approach works just fine and the patient fully recuperates, doctors also run the risk that their selected medication is not only ineffective, but could expose the patient to possibly dangerous side effects and cause the infectious bacteria to become antibiotic resistant.

Their newly developed device is centered on a microscopically small lever that vibrates in the presence of bacterial activity. A laser focused on the lever reads the vibration and then translates it into electrical signals that can be easily read. If there’s no signal, according to the researchers, that means there’s no bacteria. The entire test only takes minutes.

"This method is fast and accurate. And it can be a precious tool for both doctors looking for the right dosage of antibiotics and for researchers to determine which treatments are the most effective," explains Giovanni Dietler, a professor at EPFL and one of the researchers involved in developing the device.

The vibrations that their Nano-levers detect are actually caused by the microscopic movements of a bacterium's metabolism.

According to the researchers these metabolic movements are almost imperceptible. So in order to measure and test for this activity, the researchers first put bacteria on an extremely sensitive measuring device which in turn would vibrate a tiny lever that is only just a little bit thicker than a strand of hair if it detects metabolic activity from the microbes.

The vibrations the tiny lever produces are also incredibly small, oscillating at approximately one millionth of a millimeter. So to measure these microscopic vibrations, a laser is projected onto the lever and the light that’s reflected back is converted into an electrical signal that is then interpreted by a clinician.

Signals easy to read

The researchers say that these electrical signals are as easy to read as an electrocardiogram. If the signals produce a flat line then that means all of the bacteria are all dead. So within minutes a doctor can sample the harmful bacteria and determine whether certain antibiotic treatments would be successful or not.

"By joining our tool with a piezoelectric device instead of a laser, we could further reduce its size to the size of a microchip," says Dietler. “They could then be combined together to test a series of antibiotics on one strain in only a couple of minutes.”

The research team is now working to see if their tool could be used in other areas of medical treatment, especially oncology, the study of tumors and cancers. Using a technique similar to the one they use on bacteria, they’re trying to find out if they could measure the metabolism of tumor cells that have been exposed to cancer treatment to evaluate the efficiency of the treatment.

"If our method also works in this field, we really have a precious tool on our hands that can allow us to develop new treatments and also test both quickly and simply how the patient is reacting to the cancer treatment," says Sandor Kasas, another member of the team that developed the new device.

The study outlining the research and development of the device has been published in the latest issue of the journal, Nature Nanotechnology.

With antibiotic resistant bacterial infections on the rise, doctors say they need to be sure they are administering just the right antibiotic at the exact dosage needed to effectively and quickly treat a specific infection.

Sometimes an infection is so severe that a patient may be within hours of death unless proper treatment is given immediately.

Today, though, it takes a long time to determine that specific and crucial mix of what antibiotic to use and how much of it should be administered to a patient who may be infected with any of a countless variety of contagions.

Medical professionals must first culture the bacteria, observe its growth, and then measure the bacterial infection's response to any of a number of antibiotic treatments.

But, in cases when time is a major factor, doctors often just don’t have that luxury of using the lengthy lab work needed to help determine such specific treatment.

Past experience used to make judgment

Instead, many simply rely on their past experience and use their best judgment to select what they consider to be the most effective medication to treat their patient.

While in many cases this approach works just fine and the patient fully recuperates, doctors also run the risk that their selected medication is not only ineffective, but could expose the patient to possibly dangerous side effects and cause the infectious bacteria to become antibiotic resistant.

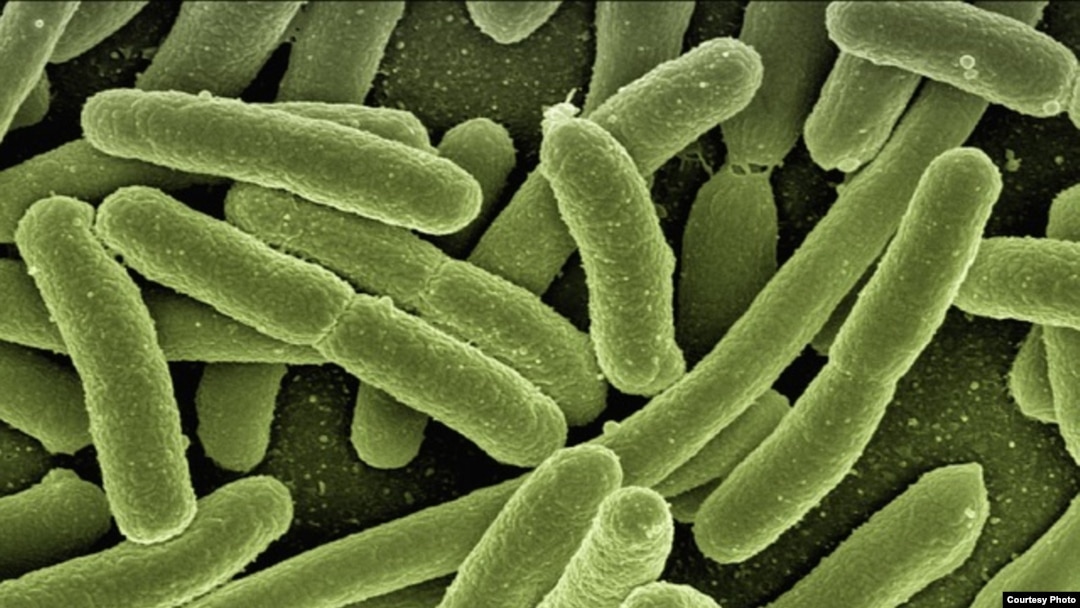

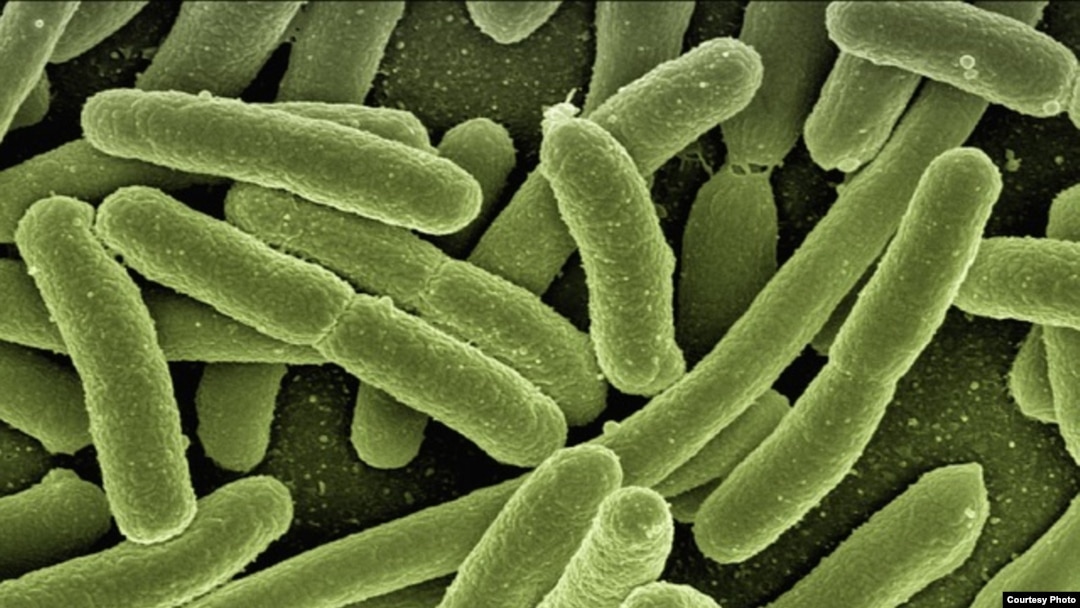

The e-coli bacteria could be identified and treated more quickly with new device.

The researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) say they found their solution at the Nano, or atomic, level.Their newly developed device is centered on a microscopically small lever that vibrates in the presence of bacterial activity. A laser focused on the lever reads the vibration and then translates it into electrical signals that can be easily read. If there’s no signal, according to the researchers, that means there’s no bacteria. The entire test only takes minutes.

"This method is fast and accurate. And it can be a precious tool for both doctors looking for the right dosage of antibiotics and for researchers to determine which treatments are the most effective," explains Giovanni Dietler, a professor at EPFL and one of the researchers involved in developing the device.

The vibrations that their Nano-levers detect are actually caused by the microscopic movements of a bacterium's metabolism.

According to the researchers these metabolic movements are almost imperceptible. So in order to measure and test for this activity, the researchers first put bacteria on an extremely sensitive measuring device which in turn would vibrate a tiny lever that is only just a little bit thicker than a strand of hair if it detects metabolic activity from the microbes.

The vibrations the tiny lever produces are also incredibly small, oscillating at approximately one millionth of a millimeter. So to measure these microscopic vibrations, a laser is projected onto the lever and the light that’s reflected back is converted into an electrical signal that is then interpreted by a clinician.

Signals easy to read

The researchers say that these electrical signals are as easy to read as an electrocardiogram. If the signals produce a flat line then that means all of the bacteria are all dead. So within minutes a doctor can sample the harmful bacteria and determine whether certain antibiotic treatments would be successful or not.

A technician displays MRSA bacteria strain - a drug-resistant "superbug" at a laboratory in Berlin.

While their device is already very small the researchers are hoping to shrink their device to an even smaller size."By joining our tool with a piezoelectric device instead of a laser, we could further reduce its size to the size of a microchip," says Dietler. “They could then be combined together to test a series of antibiotics on one strain in only a couple of minutes.”

The research team is now working to see if their tool could be used in other areas of medical treatment, especially oncology, the study of tumors and cancers. Using a technique similar to the one they use on bacteria, they’re trying to find out if they could measure the metabolism of tumor cells that have been exposed to cancer treatment to evaluate the efficiency of the treatment.

"If our method also works in this field, we really have a precious tool on our hands that can allow us to develop new treatments and also test both quickly and simply how the patient is reacting to the cancer treatment," says Sandor Kasas, another member of the team that developed the new device.

The study outlining the research and development of the device has been published in the latest issue of the journal, Nature Nanotechnology.