Havre de Grace, Maryland is a popular destination for hunters because it's located where the Susquehanna River flows into the Chesapeake Bay, a well-known habitat for waterfowl.

However, more and more visitors to the small town are seeking a different kind of bird — wooden decoys, the town’s traditional craft.

Self-proclaimed decoy capital of the world

Capt. Bob Jobes brings his boat into dock, returning with his son after a day of crabbing in the Chesapeake Bay.

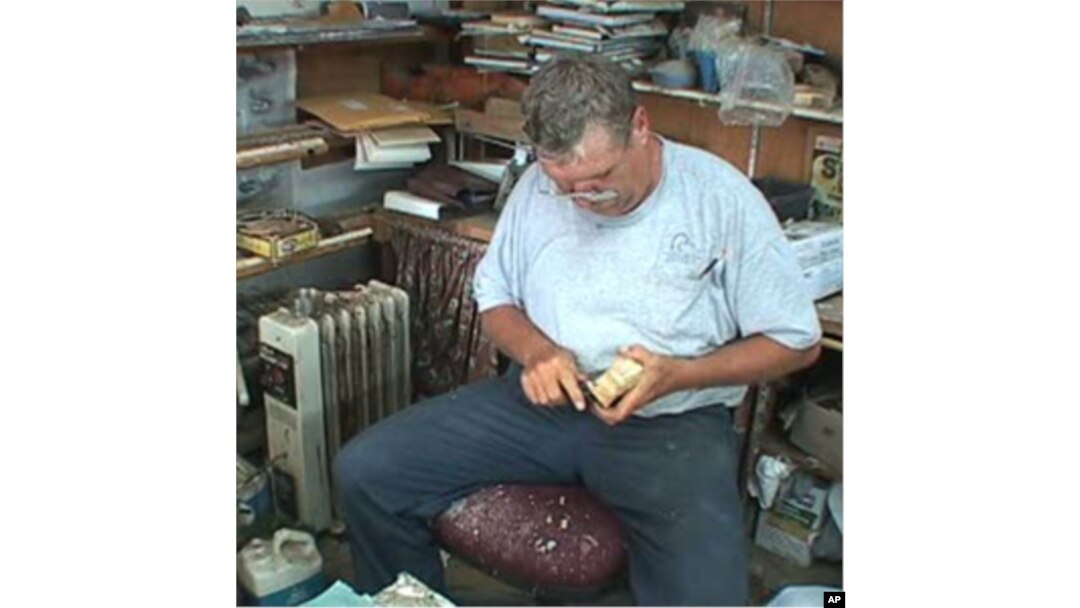

Like many others here, Jobes fishes for a living. But when he's not on the water, he's working in the shed behind his house, carving wooden decoys.

“It was just growing up as a kid, learning a skill how to do this," he says. "I've got two brothers that carve, my son carves and my father. Yeah. Three generations carving decoys.”

Bob Jobes hard carves a wooden decoy duck.

Hunters traditionally use decoys to lure waterfowl - mostly ducks and geese - close enough to shoot.

Decoys are so revered here that the town calls itself the decoy capital of the world.

Decoy museum

Havre de Grace even has a decoy museum, where about 1,000 decoys are on display. Most were handmade in the Chesapeake Bay region.

"Approximately 14,000 visitors come here each year," says John Sullivan, director of the museum. "We have visitors from all over the United States and all over the world.”

Henry Miner came from the Chicago area to see the decoys. "I particularly like the older ones, the very first styles and anything that is wood because, nowadays, everything is plastic or foam, so they are pretty neat to look at."

According to Sullivan, the demand for decoys took off in the mid 19th century when hunters began to use sink boxes, which were floating platforms surrounded by decoys.

“You would use from 200 to 500 decoys around these gunning devices," he says. "And that demand put a lot of the housepainters and carpenters in the business of producing decoys.”

American folk art

The demand for decoys declined after sink boxes were outlawed in 1935. That's when people began to perceive the wooden birds as form of American folk art.

“People were collecting decoys and we were selling so many decoys that we could just totally make a living off of carving," says Jobes. "It's changing a little bit now, with the economy."

Decoys are beloved in Havre de Grace. They sit in restaurants, adorn shop windows and decorate homes, including Mitch Shank's. His grandfather, R. Madison Mitchell, was the most prolific decoy carver in town.

Shank started collecting decoys as a teenager, when he worked for his grandfather.

"In Havre de Grace, if you drove around town and knocked on a door," he says, "most of the houses would probably have at least one decoy.”

Wooden decoys, here in Vincenti's shop in Havre de Grace, Md., can sell for up to several thousand dollars.

Carrying on the tradition

Jeannie Vincenti and her husband, who run a store in town, are also carvers.

"Our customers are local people who are aware of the tradition," says Vincenti. "There are also tourists that come in and do not understand quite exactly what a decoy may be, but when they come in they find something in the store that they like and consider a treasure."

Prices for a decoy can range from $50 to several thousand. One antique decoy in Vincenti's shop has a price tag of almost $5,000.

The shop also sells carving supplies.

“There are younger people coming into it every day," she says. "Is it the number that we saw years ago? Probably not."

Vincenti hopes more young people become decoy carvers so the tradition will continue, allowing Havre de Grace to continue to call itself the decoy capital of the world.