Thailand’s boisterous youth movement is linking up with the kingdom’s most enduring pro-democracy force — the “Red Shirt” protest veterans — posing the most serious threat yet from the street to Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha’s grip on power.

But experts say as long as the former army chief retains the support of Thailand’s core interest groups, the monarchy, the military and big business, he is unlikely to fall, no matter how many push for his removal from office.

Your browser doesn’t support HTML5

Protest Veterans in Thailand Join Young Pro-Democracy Demonstrators

Almost daily protests, spurred by the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic and an unprecedented economic crunch, are swelling. By dusk parts of Bangkok are covered in choking swirls of tear gas while fires rage, set by a hard core of young protesters clashing with police.

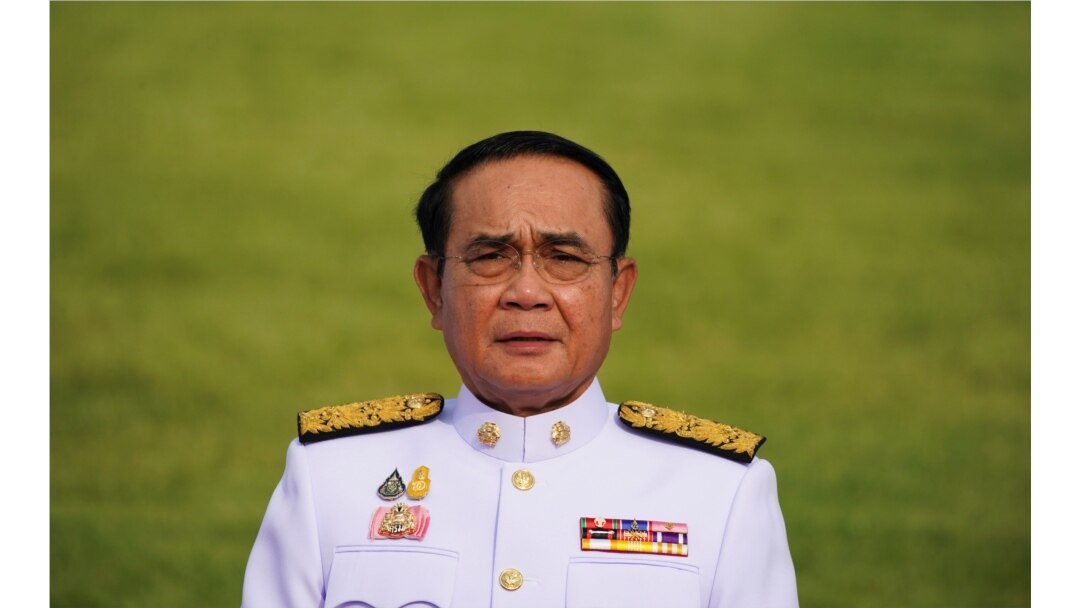

Thailand's Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha attends a family photo session at the Government House in Bangkok, Thailand, March 30, 2021.

The violence, experts warn, could lead to the army coming out and a deepening of the political crisis engulfing the turbulent nation.

Tens of thousands of people joined loud, colorful convoys of “car mobs” across the country Sunday, calling on Prayuth to resign. The convoys rode through Bangkok and the “Red Shirt” rural heartlands of north and northeastern Thailand.

At the helm in the capital was Nattawut Saikuar, a former Red Shirt hero, who pulled out his old followers as leader of the new “Oust Prayuth Network” alongside thousands of young "Gen Z” protesters.

“This is a synergy between two generations fighting a common enemy,” Nattawut told VOA.

The Red Shirt movement began in 2008 in outrage at an appointed government which followed a coup that ousted Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

A few years later, their protests were put down with a bloody army crackdown led by Prayuth.

In 2014 as army chief, Prayuth led another coup against another elected government, this time led by Yingluck Shinawatra, Thaksin’s younger sister. The Reds were forced into retreat.

“These young people have taken up the baton,” Nattawut added.

Police use a water cannon and tear gas to disperse protesters taking part in a demonstration calling for the resignation of Thailand's Prime Minister Prayut Chan-ocha.

New political wisdom

Thailand’s Gen Z, angry, articulate and armed with social media, have challenged Thailand’s power pyramid like never before, calling for Prayuth to resign and a new constitution to unplug the army from politics for good and, crucially, reform of the all-powerful monarchy.

“Frankly, before Prayuth’s coup I was just a normal school kid,” a 25-year-old protester who gave her name as Pop said, as she daubed "Prayuth Get Out” on a road in spray paint.

“But as time goes by you realize politics affects us all. That’s when I took to the street and joined the movement demanding this government fall.”

Experts say Thailand’s arch-royalist establishment sees Prayuth as an integral part of the hierarchy that has been carefully constructed to keep populist civilian leaders like the Shinawatras out, while leaving the monarchy above reproach and tycoons to dominate the economy.

“Prayuth is now not only protecting his position, but also protecting the advantages of an establishment that has benefited from the past few years,” political scientist Kanokrat Lertchoosakul told VOA News.

And that means, no matter how bad things get on the street — with a coronavirus pandemic claiming scores of lives each day, low vaccination rates and the economic growth forecast to be rubbed out for the year — Prayuth is unlikely to budge.

“The elite need to keep him in power,” prominent historian Nidhi Eoseewong said during Sunday’s car mob.

“Prayuth knows all too well that it’s not up to him to step down or not, it’s up to the powers behind him who will decide.”

Undeterred, the young protesters have gone after him for more than a year.

This picture taken on March 25, 2019, shows exiled former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra being interviewed by Agence France-presse in Hong Kong.

They are also filling up rooms on the Clubhouse app, for chats hosted by the 72-year-old Thaksin from his self-exile abroad, even though most are too young to remember the enigmatic billionaire.

His youth appeal has raised prospects of a remarkable comeback of sorts, especially as the economy sinks further and the government runs out of cash and ideas.

But unlike the loyalties of the past, "Gen Z” has a “new political wisdom,” warns Kanokrat, explaining they will not back leaders who play old power games at the expense of their demands.

“If we don’t listen and turn them into a very high potential human resource for the future, we are turning them into the state enemy,” Kanokrat said.