Complete the following sentence:

“You go to the library to check out . . . . .?"

The obvious answer is “books.” But a harder question might be, “What do we mean by ‘book’?”

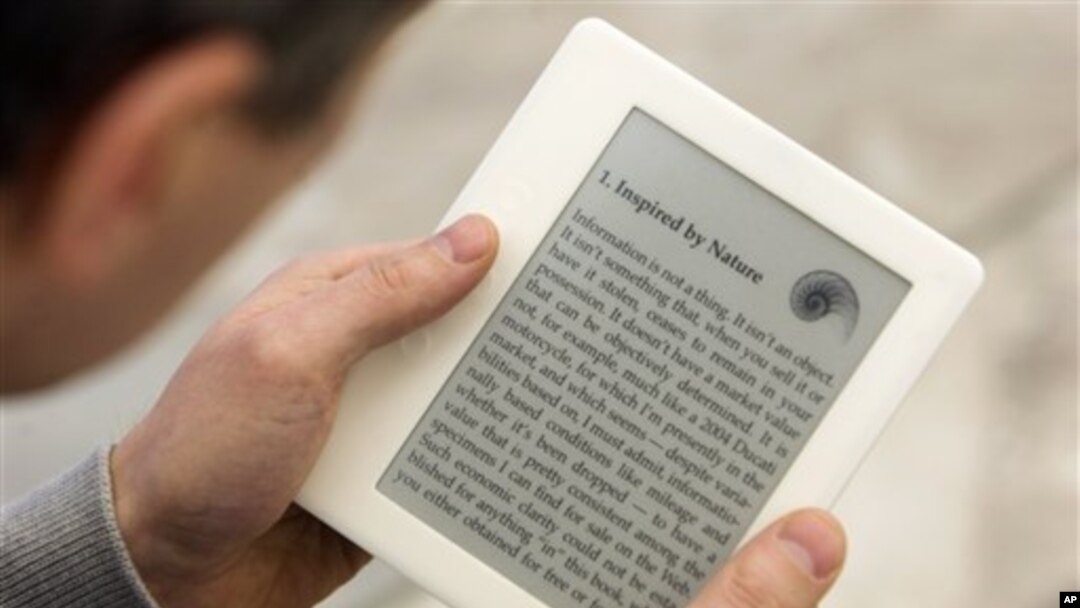

Electronic books or “e-books,” have established a firm foothold in American society.

The big online bookseller Amazon, for instance, recently announced that less than four years after introducing them to its catalog, it's now selling more electronic versions of its book titles than printed ones.

And this past April, Encyclopedia Britannica, the world’s oldest and largest maker of encyclopedias - a staple at any library - announced it would no longer publish a print edition.

Last week, the Pew Internet & American Life Project released a survey about the use of e-books by library patrons. It found that 12 percent of Americans age 16 and older who read e-books say they had borrowed at least one from a library within the past year.

But the survey found that the broader public, including 58 percent of those who have library cards and 53 percent of people who own electronic book readers, are not aware that they can find and check out e-books from public libraries, even though three-quarters of the libraries offer that service.

Pew Internet Project director Lee Rainie noted that e-book borrowing is becoming more popular at the same time that publishers - who are selling plenty of e-books and fewer hard-copy editions - are worried that free e-book check-outs at the library will hurt sales.

In February, for instance, the big publisher Penguin Books stopped supplying new e-books and audio books to libraries.

Penguin just reached an agreement to resume supplying one big library system - in New York City - but not until six months after new titles are released. That way, those who want the latest books will have to buy them.

So things are a little murky in the library world when it comes to electronic books.

More and more patrons want them, but publishers are giving the libraries a hard time about offering them. Demand’s not the problem. Supply may soon be.

“You go to the library to check out . . . . .?"

The obvious answer is “books.” But a harder question might be, “What do we mean by ‘book’?”

Electronic books or “e-books,” have established a firm foothold in American society.

The big online bookseller Amazon, for instance, recently announced that less than four years after introducing them to its catalog, it's now selling more electronic versions of its book titles than printed ones.

And this past April, Encyclopedia Britannica, the world’s oldest and largest maker of encyclopedias - a staple at any library - announced it would no longer publish a print edition.

Last week, the Pew Internet & American Life Project released a survey about the use of e-books by library patrons. It found that 12 percent of Americans age 16 and older who read e-books say they had borrowed at least one from a library within the past year.

But the survey found that the broader public, including 58 percent of those who have library cards and 53 percent of people who own electronic book readers, are not aware that they can find and check out e-books from public libraries, even though three-quarters of the libraries offer that service.

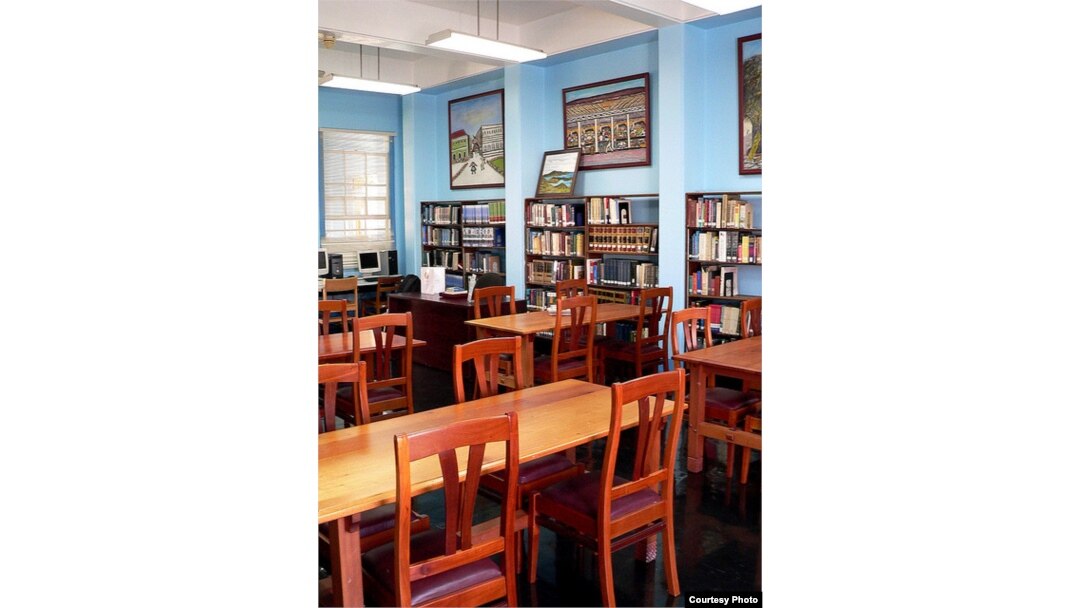

You don't see e-books on the shelves of this modern public library, but it's a good bet you'll find some elsewhere in that branch. (viasta2, Flickr Creative Commons)

Pew Internet Project director Lee Rainie noted that e-book borrowing is becoming more popular at the same time that publishers - who are selling plenty of e-books and fewer hard-copy editions - are worried that free e-book check-outs at the library will hurt sales.

In February, for instance, the big publisher Penguin Books stopped supplying new e-books and audio books to libraries.

Penguin just reached an agreement to resume supplying one big library system - in New York City - but not until six months after new titles are released. That way, those who want the latest books will have to buy them.

So things are a little murky in the library world when it comes to electronic books.

More and more patrons want them, but publishers are giving the libraries a hard time about offering them. Demand’s not the problem. Supply may soon be.