The Egyptian media erupted in excitement during the coup attempt in Turkey, prematurely declaring it successful. A headline on one prominent paper read, “The military force’s message: relationships with the world will continue.”

Even weeks later, many Egyptians who follow their government’s lead in its disdain for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, deem the coup attempt successful in at least one respect: It made the Turkish president look bad.

“It did not succeed because he is still in power,” said 22-year-old Sherif Adel on his way home from a job interview in Cairo.“But he did lose a lot.”

Sherif Adel agrees with the Egyptian government, which blocked a United Nations Security Council Statement calling on the international community to "respect the democratically elected government of Turkey."

In the aftermath of the July 15 coup attempt, tens of thousands of people in Turkey have been arrested, detained or fired in a crackdown on suspected mutineers, drawing criticism from human rights groups.

Egyptian commentators jumped on the crackdown. Some suggested Erdogan himself staged the coup as an excuse to purge his enemies. At the United Nations, Egypt blocked efforts to release a Security Council statement calling on the international community to "respect the democratically elected government of Turkey."

Turkey fired back insults. Erdogan said Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi "has nothing to do with democracy. He killed thousands of his own people,” according to Egyptian state-owned news organizations.

In response, the Egyptian foreign ministry released a statement saying the Turkish president "is continuing to confuse matters and lose the compass of sound judgment."

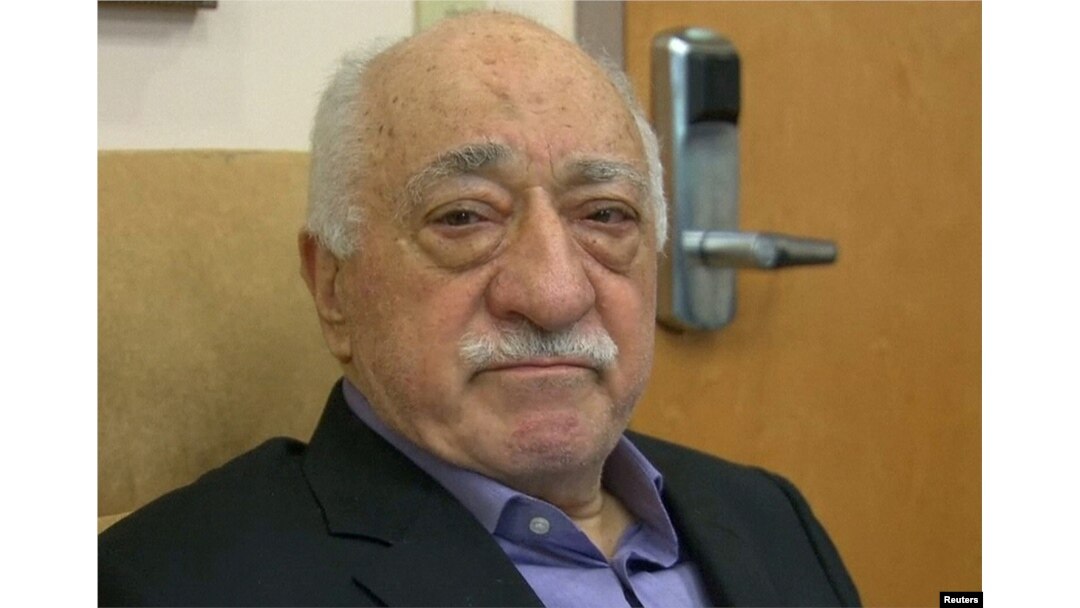

And as Turkey continues to demand the U.S. extradition of Fethullah Gulen, the 75-year-old cleric accused by Ankara of plotting the coup, officials in Cairo suggest Gulen may find political asylum in Egypt.

U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gulen, whose followers Turkey blames for a failed coup, is shown in still image taken from video, as he speaks to journalists at his home in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, July 16, 2016.

Political Islam

The already-strained relationship between Egypt and Turkey will continue to deteriorate, analysts say, as long as both countries maintain their stances on Islamist politics.

"Egyptian-Turkish relations simply boil down to the Muslim Brotherhood," said Ziad Akl, a senior researcher at the Al Ahram Center for Strategic Studies in Cairo. "Egypt will support any kind of action that will get rid of that mentality."

Sissi took power in 2013, overthrowing the elected, yet deeply unpopular, President Mohamed Morsi, who led the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood party. In the years since, Sissi’s government has banned the Muslim Brotherhood and branded it a terrorist organization.

Former Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi, wearing a red jumpsuit that designates he has been sentenced to death, raises his hands inside a defendants cage in a makeshift courtroom at the national police academy, in an eastern suburb of Cairo, June 18, 2016.

Turkey, which supports the Muslim Brotherhood, was allied with Morsi and continued to bate Sissi, even after he was formally elected in 2014, calling his initial ascension to power the product of a “coup,” not a popular “revolution” as Egyptian government supporters insist.

The failed coup in Turkey also vaguely echoes 2013 events in Egypt, and on the streets of Cairo, some Egyptians are re-visiting the political polarity that had faded from public discourse amid current economic woes.

“Many people have the idea that Turkey is a country that supports the Muslim Brotherhood, and that they are terrorists,” observes 32-year-old Mahmoud, a bus driver. “But I think the Turkish leadership is respectable.”

Mahmoud says Egyptian people are divided in their loyalties in Turkey based on their opinions of the Muslim Brotherhood, banned in Egypt.

Potential consequences

“The million dollar question becomes: Would regional alliances be the same after more disturbance?” asked Akl, of Al Ahrum.“Could we witness growing bipolar relations?”

A bipolar relationship between two countries loosely describes a rivalry between two large powers that develop exclusive alliances. For example, during the Cold War, a country could be allied with the United States or Russia, but not both.

Rivals Saudi Arabia and Iran, the two largest powers in the Middle East are often said to have bipolar relations, with battle lines drawn in multiple wars behind the two giants.

Turkey and Egypt are on the same side in conflicts in Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Iraq, and their coalitions’ abilities to fight could be damaged if their relationship crumbled. At present Turkey and Egypt maintain normal relations despite the squabble.

Akl added Turkey-Egypt relations are not likely to disintegrate as acutely as Iran-Saudi relations, which have had no formal diplomatic ties since early this year. The two countries consider each other an imminent threat, supporting opposite sides in the conflicts in Syria and Yemen.

But nothing in this region is simple.Saudi Arabia and Iran officially support the same side in the Arab-Israeli conflict and the fight against Islamic State militants. Besides hindering mutually beneficial economic ties, souring relations between Egypt and Turkey could “make regional politics more complicated,” said Akl.

Khalifa Gaballah, the foreign affairs editor at Almasry Alyoum in Cairo, warns the rift between Egypt and Turkey, two of the most influential countries in the Middle East could be dangerous for entire region.

And the consequences of escalation could be dangerous for all, added Khalifa Gaballah, the foreign affairs editor at Almasry Alyoum, a prominent Egyptian newspaper.

“The continued estrangement and tensions is not just a hazard to the two countries,” he said.“It also is potentially harmful for the whole region.”

(Hamada Elrasam contributed to this report.)