NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory – Curiosity Rover – was sent to Mars some 16 months ago with a major objective of finding evidence of a past environment that would be well suited to supporting microbial life.

Today, a team of mission researchers, writing in a series of papers published in the journal Science, said that they found evidence of what was once an ancient freshwater lake on Mars that might have been capable of supporting life.

The findings were also announced this morning by members of the research team who addressed the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

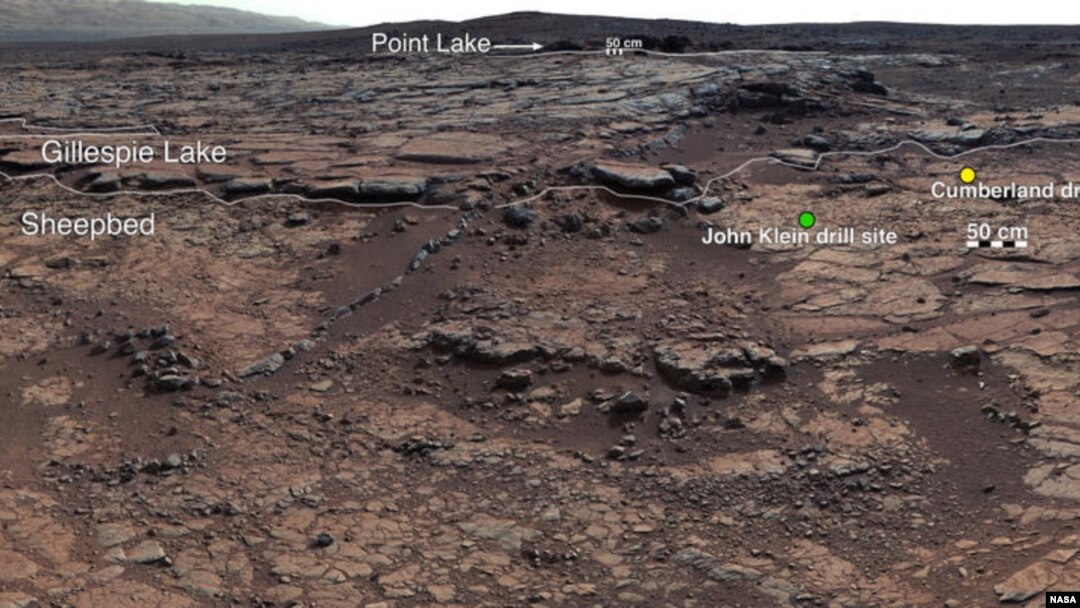

The researchers studied a set of sedimentary rock outcrops that were found in an area on the floor of Gale Crater called Yellowknife Bay, near the Mars equator.

These sedimentary rocks that probably formed from ancient Martian mud or clay have suggested to researchers that there was at least one lake that welled up with what could have been drinkable water inside of Gale Crater some 3.6 million years ago,

and that the lake could have lasted for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years.

“Shortly after we landed, Curiosity found evidence that liquid water had flowed across the surface long ago in Gale crater,” said Jim Bell, from Arizona State University and an author of four of the papers. “These new results, however, come from the first drilling activities ever performed on Mars, and they show that in addition to surface water, there was likely an active groundwater system in Gale crater that significantly weathered ancient rocks and minerals.”

The mudstones analyzed by the research team are normally formed in calm conditions and produced by very fine sediment grains settling on each other layer-by-layer, in still water.

The team’s analysis of Yellowknife Bay's clay-rich lakebed habitat showed that a calm and fresh water lake that contained basic but crucial biological elements such as carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur existed at least once inside the Gale Crater.

According to the team, a lake like the one they think once flowed on Mars could have provided perfect conditions for simple bacterial life such as chemolithoautotrophs, which are rock-eating microbes that live on and derive their energy from mineral compounds.

The researchers pointed out that they did not find signs of ancient life itself on Mars.

"It is exciting to think that billions of years ago, ancient microbial life may have existed in the lake's calm waters, converting a rich array of elements into energy. The next phase of the mission, where we will be exploring more rocky outcrops on the crater's surface, could hold the key to whether life did exist on the red planet,” said another of the paper’s co-authors, Sanjeev Gupta from Imperial College London, who is also a member of the MSL mission team.

The researchers will continue to use the Mars roving science laboratory to continue exploring Gale Crater for even more evidence of ancient lakes or other habitable environments.

Today, a team of mission researchers, writing in a series of papers published in the journal Science, said that they found evidence of what was once an ancient freshwater lake on Mars that might have been capable of supporting life.

The findings were also announced this morning by members of the research team who addressed the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

The researchers studied a set of sedimentary rock outcrops that were found in an area on the floor of Gale Crater called Yellowknife Bay, near the Mars equator.

These sedimentary rocks that probably formed from ancient Martian mud or clay have suggested to researchers that there was at least one lake that welled up with what could have been drinkable water inside of Gale Crater some 3.6 million years ago,

and that the lake could have lasted for tens or even hundreds of thousands of years.

“Shortly after we landed, Curiosity found evidence that liquid water had flowed across the surface long ago in Gale crater,” said Jim Bell, from Arizona State University and an author of four of the papers. “These new results, however, come from the first drilling activities ever performed on Mars, and they show that in addition to surface water, there was likely an active groundwater system in Gale crater that significantly weathered ancient rocks and minerals.”

The mudstones analyzed by the research team are normally formed in calm conditions and produced by very fine sediment grains settling on each other layer-by-layer, in still water.

The team’s analysis of Yellowknife Bay's clay-rich lakebed habitat showed that a calm and fresh water lake that contained basic but crucial biological elements such as carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur existed at least once inside the Gale Crater.

According to the team, a lake like the one they think once flowed on Mars could have provided perfect conditions for simple bacterial life such as chemolithoautotrophs, which are rock-eating microbes that live on and derive their energy from mineral compounds.

The researchers pointed out that they did not find signs of ancient life itself on Mars.

"It is exciting to think that billions of years ago, ancient microbial life may have existed in the lake's calm waters, converting a rich array of elements into energy. The next phase of the mission, where we will be exploring more rocky outcrops on the crater's surface, could hold the key to whether life did exist on the red planet,” said another of the paper’s co-authors, Sanjeev Gupta from Imperial College London, who is also a member of the MSL mission team.

The researchers will continue to use the Mars roving science laboratory to continue exploring Gale Crater for even more evidence of ancient lakes or other habitable environments.