Italy’s president was accused Sunday of pandering to the European Union and kowtowing to the financial markets after he withheld his approval of a euro-skeptic becoming the country’s economy minister, thwarting in the process the formation of Europe’s first all-populist government.

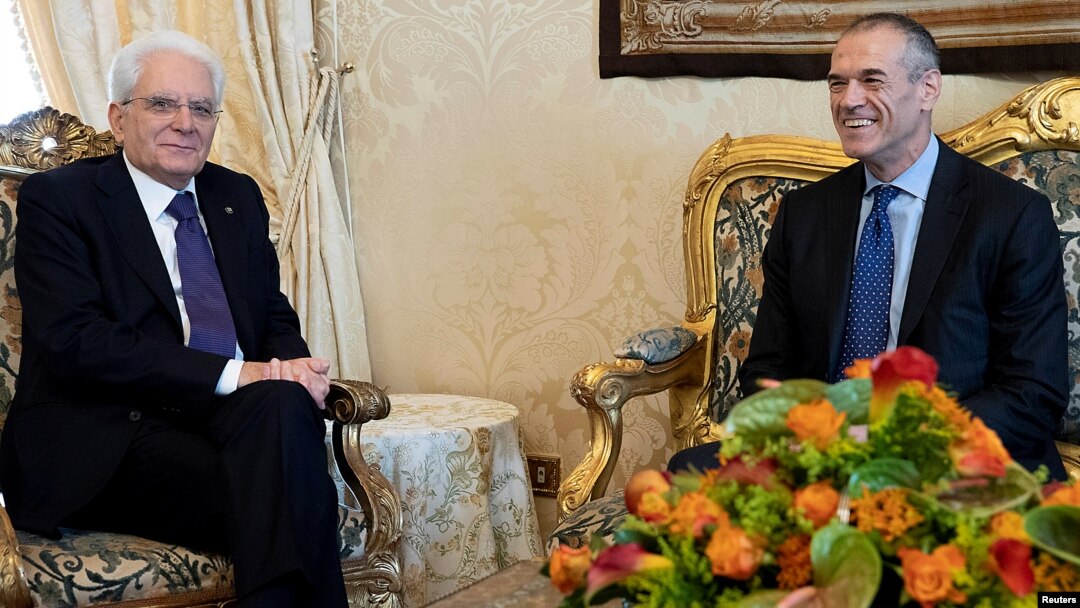

President Sergio Mattarella’s move plunged Italy deeper into a dramatic full-blown constitutional crisis — dangerous even by the country’s own chaotic political standards — with angry populists calling for the head of state’s impeachment. Mattarella turned Monday to a former International Monetary Fund economist, Carlo Cottarelli, to see if he can head a caretaker government of technocrats.

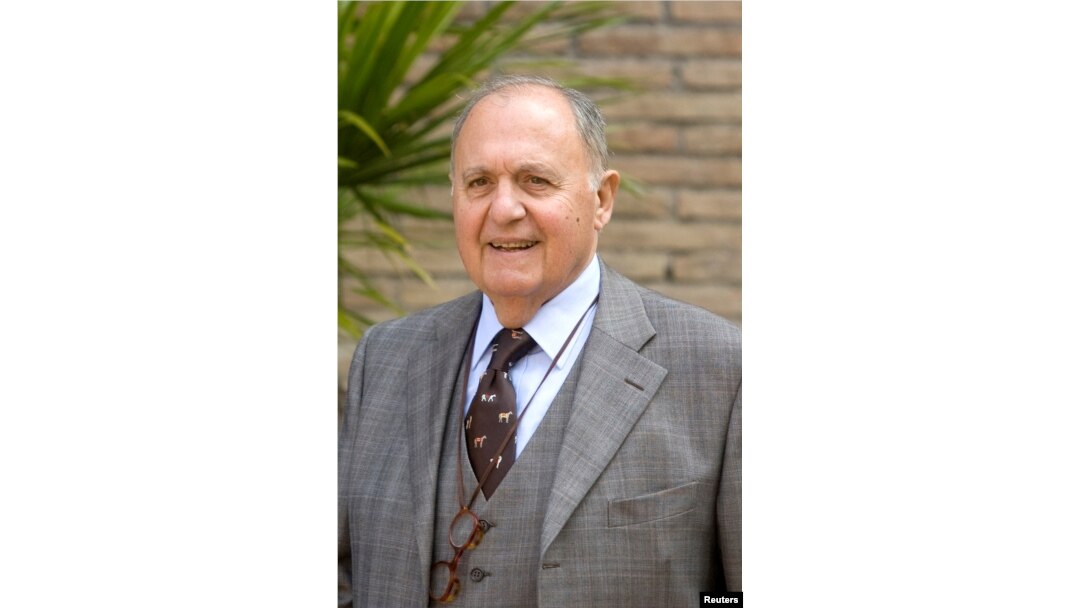

FILE - Paolo Savona is pictured during a meeting in Rome, April 11, 2011.

His rejection of 81-year-old Paolo Savona, an opponent of the euro, as economy minister appears likely to have increased the chances of a fresh parliamentary election this year which, unlike March’s inconclusive polls, will probably have the European Union and euro membership as central campaigning issues, raising the stakes for Brussels and threatening a fracture with the bloc.

Luigi Di Maio, the youthful head of the anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S), vented his fury at the collapse of talks that would have seen his party form a coalition government with the Matteo Salvini’s far-right anti-immigrant League. On Facebook, he said he and Salvini had been ready to form the government. “I am very angry. You can imagine how much time we spent trying to form a government over the last 80 days,” he wrote.

FILE - Anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S) leader Luigi Di Maio speaks to the press after a meeting with Italian President Sergio Mattarella as part of consultations of political parties to form a government, on May 14, 2018 at the Quirinale palace in Rome.

He blamed “the credit rating agencies” and “the financial lobbies” for torpedoing the nascent government, adding that Mattarella’s veto was unacceptable and had thrust Italy into “an institutional clash without precedent.” He argued the president, a former judge and veteran politician who has served in several Christian Democrat governments, should be impeached. On Italian television the M5S leader said: “First the impeachment of Mattarella... then to the polls.”

FILE - League party leader Matteo Salvini speaks to the media at the Quirinal Palace in Rome, Italy, April 5, 2018.

An equally enraged Salvini pointed the finger of blame for the deepening crisis at European Union officials and warned darkly, “We will not be blackmailed by anyone.” The only option now, he said, is for Italy to hold yet another election. “If we are in a democracy, there is only one thing to do: give the choice back to the Italians.”

Italian Premier-designate Giuseppe Conte (C) is approached by journalists as he leaves his home, in Rome, May 24, 2018.

Italy’s Prime Minister-designate, Giuseppe Conte, a political novice who was plucked from academic obscurity by Di Maio and Salvini to act as premier for their coalition government, tendered his resignation Sunday. He had been putting the finishing touches to his Cabinet line-up last week but the reaction from financial markets was far from approving with Italian government bond prices slumping and the country’s ailing banks seeing their stock prices hit an 11-month low.

Former senior International Monetary Fund (IMF) official Carlo Cottarelli arrives to talk to the media after a meeting with Italy's President Sergio Mattarella at the Quirinal Palace in Rome, Italy, May 28, 2018.

Mattarella said he had vetoed the appointment of Savona as economy minister as it was his constitutional duty to protect Italy’s financial interests. Mattarella said he had accepted every proposed minister except Savona, who has called the euro a “German cage” and in the past has compared Germany’s post-World War II rulers to Nazis.

Mattarella said he had done “everything possible” to assist the populist parties strike a deal that would give Italy's hung parliament a majority. But he added that a minister like Savona “could probably, or even inevitably, provoke Italy's exit from the euro.”

Under the Italian constitution, ministers are appointed by the president in consultation with a prime minister-designate. It is not the first time that an Italian head of state has vetoed a minister proposed by an incoming government. It has happened at least three times before, most recently when Silvio Berlusconi — after winning the 1994 elections — wanted his personal lawyer to become the justice minister.

Italian former premier and leader of Forza Italia (Let's Go Italy) party Silvio Berlusconi listens to reporters at a polling station in Milan, March 4, 2018.

Investors were not the only ones alarmed about the prospects of an incoming M5S-League coalition government, which for the EU represented the biggest challenge for Brussels since Brexit with the populist threats to break the bloc’s budgetary rules and to deport summarily half-a-million migrants.

FILE - Migrants wait to disembark from "Vos Prudence" offshore tug supply ship as they arrive at the harbor in Naples, Italy, May 28, 2017.

All of last week a series of senior European and EU officials warned of catastrophe with Slovakia’s finance minister, Peter Kazimir, urging Italy against a “suicide mission” that could trigger another eurozone debt crisis.

The cautions drew sharp retorts from the populists of both parties, with M5S politician Roberta Lombardi saying, “We won’t take lectures from Brussels. They should shut up.” She added: “If Europe fights us on our spending plans, we might be forced to let the people have their say in a referendum. I think that about 80% would vote to get rid of the euro.”

M5S and League officials say that Mattarella’s veto and Italy’s relationship with Brussels will inevitably frame any election. They calculate the head of state will have to call elections for September or October. March’s election was one of the most bad-tempered and violent since the 1980s and some analysts fear fresh elections could turn even nastier.