If you ask Americans to name a famous architect, chances are they’ll think first of Frank Lloyd Wright.

His modernist, minimalist buildings, designed to blend with nature, revolutionized architectural thinking in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Wright was born on a Wisconsin farm in 1867, two years after the end of the U.S. Civil War. He lived to see the Soviet Union send a satellite into space.

Even before he was born, his schoolteacher-mother decided that Frankie, as she called him, would be an architect.

Bright and curious, the lad obliged by arranging blocks and paper in the shapes of simple buildings and furniture.

Wright apprenticed in Chicago under the designers of the world’s first true skyscrapers.

Eventually he inherited his family’s Wisconsin farm, where he built one of the world’s most famous houses - Taliesin. Wright called it “the supreme natural house” that blended so well into the surroundings that it was hard to tell where floor left off and the ground began.

Using what he called his “Usonian style” - the name comes from the abbreviation for the United States: “U.S.” - the architect designed low, flat homes for his clients that many likened to works of modern art.

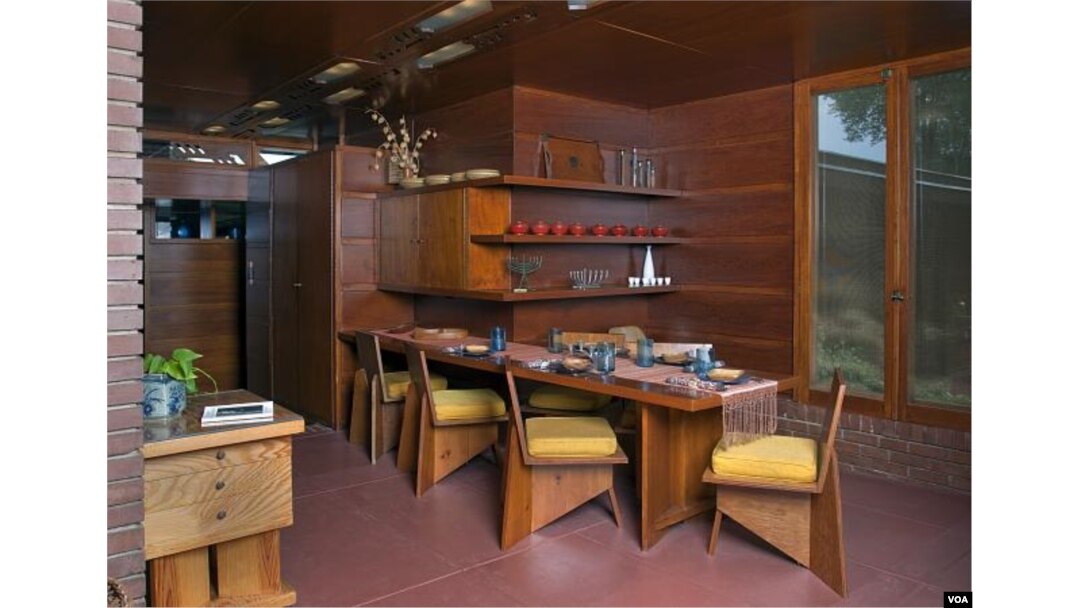

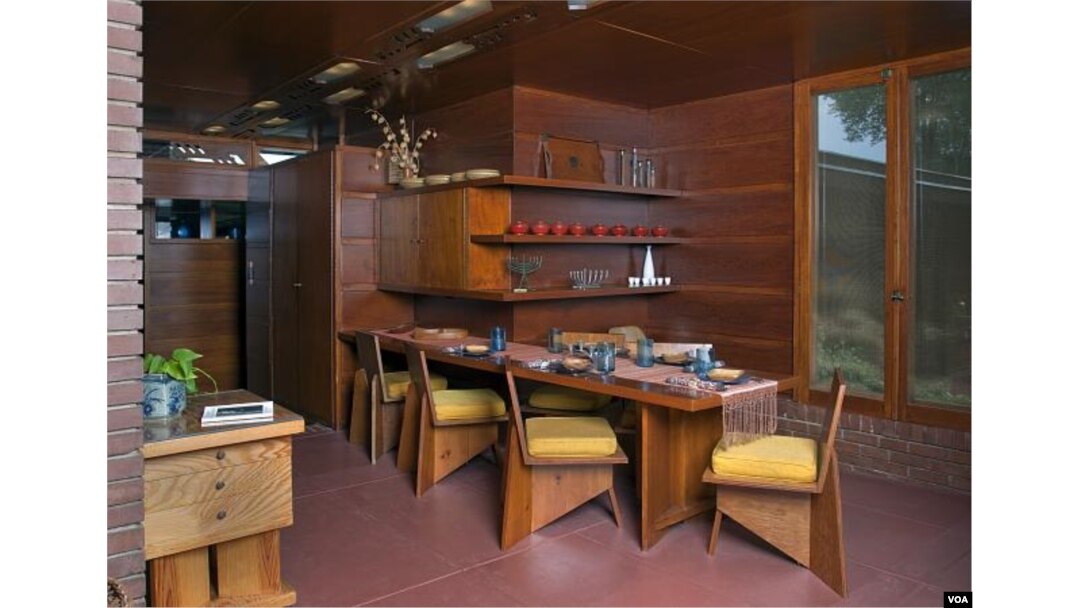

Avoiding classical columns and scrolls and other flourishes, Wright opted for long rooms with lots of severe angles, and built-in shelves that ran the length of his one-story houses.

They were not what you would call “warm and cozy.”

Clients loved to show off their homes but found the austere wooden furniture - sometimes secured in place and difficult to move - as uncomfortable as park benches.

Floor-to-ceiling windows let in drafts. And worst of all, most of the roofs leaked.

Some of Wright’s customers put up with it all as a sacrifice for the sake of art and design.

Mildred Rosenbaum in Florence, Alabama, whose low-slung Frank Lloyd Wright house stood out starkly on a street full of typical white-columned mansions in that Deep South city, admitted that her family sometimes grew tired of living in an architectural laboratory in which so many tables and chairs and beds were bolted down.

She said she worried that her kids might get up in the middle of the night sometime and unscrew the place.

His modernist, minimalist buildings, designed to blend with nature, revolutionized architectural thinking in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Wright was born on a Wisconsin farm in 1867, two years after the end of the U.S. Civil War. He lived to see the Soviet Union send a satellite into space.

Even before he was born, his schoolteacher-mother decided that Frankie, as she called him, would be an architect.

Bright and curious, the lad obliged by arranging blocks and paper in the shapes of simple buildings and furniture.

Wright apprenticed in Chicago under the designers of the world’s first true skyscrapers.

You might use words like “efficient” and “functional” to describe the Rosenbaum House’s living quarters. “Comfy” and “snug,” not so much. (Carol M. Highsmith)

Eventually he inherited his family’s Wisconsin farm, where he built one of the world’s most famous houses - Taliesin. Wright called it “the supreme natural house” that blended so well into the surroundings that it was hard to tell where floor left off and the ground began.

Using what he called his “Usonian style” - the name comes from the abbreviation for the United States: “U.S.” - the architect designed low, flat homes for his clients that many likened to works of modern art.

Avoiding classical columns and scrolls and other flourishes, Wright opted for long rooms with lots of severe angles, and built-in shelves that ran the length of his one-story houses.

They were not what you would call “warm and cozy.”

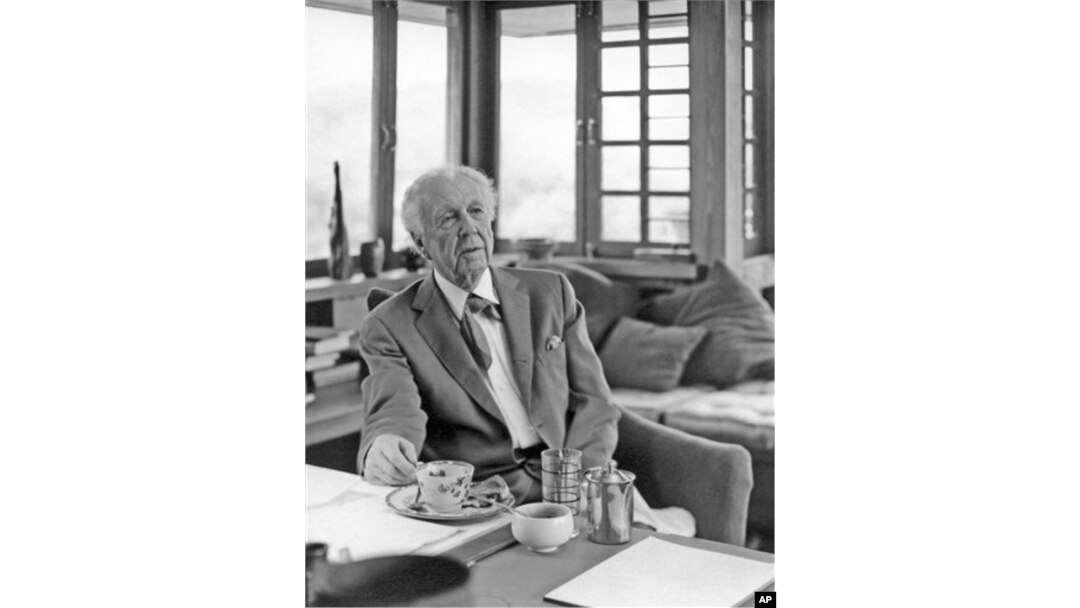

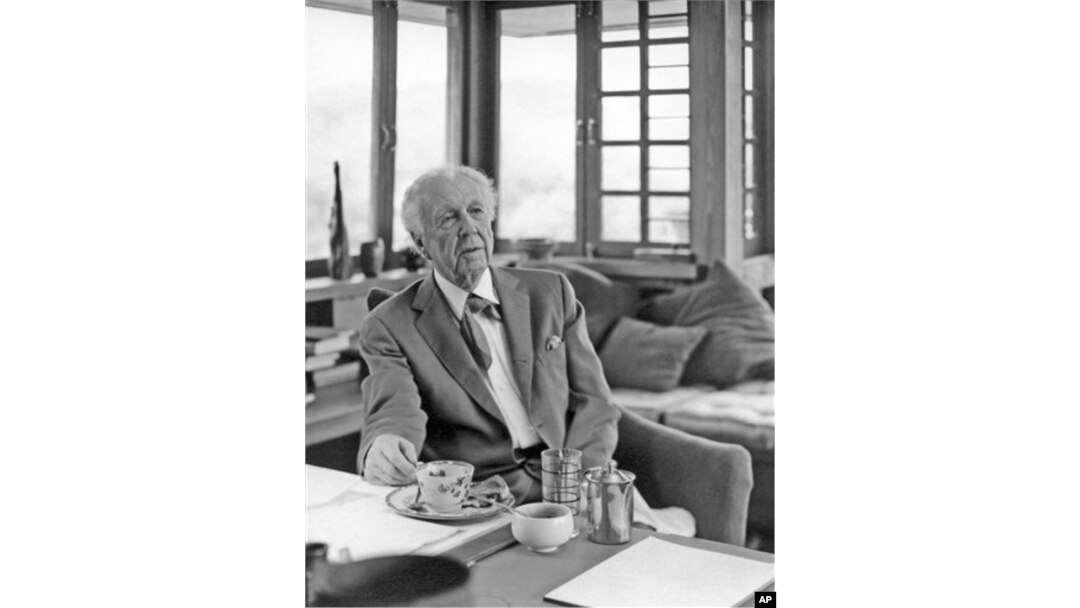

Frank Lloyd Wright in 1955 at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin. (AP Photo/Courtesy Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, John Engstead)

Especially not warm, since Wright was a creative architect but a terrible engineer.Clients loved to show off their homes but found the austere wooden furniture - sometimes secured in place and difficult to move - as uncomfortable as park benches.

Floor-to-ceiling windows let in drafts. And worst of all, most of the roofs leaked.

Some of Wright’s customers put up with it all as a sacrifice for the sake of art and design.

Mildred Rosenbaum in Florence, Alabama, whose low-slung Frank Lloyd Wright house stood out starkly on a street full of typical white-columned mansions in that Deep South city, admitted that her family sometimes grew tired of living in an architectural laboratory in which so many tables and chairs and beds were bolted down.

She said she worried that her kids might get up in the middle of the night sometime and unscrew the place.