There wasn’t much for a lonely American sailor to do on leave in Reykjavik, Iceland in 1966. The land of fire and ice seemed like galaxies away from Red Rock, Oklahoma, home to the Otoe-Missouria tribe since the early 1880s.

As fate would have it, he met a pretty Icelandic woman with the name of a Roman goddess. Maybe it was during an evening spent at a bar off base. The sailor told her he was an American Indian, but it’s unlikely he ever mentioned his childhood on a reservation or the grim years in boarding school.

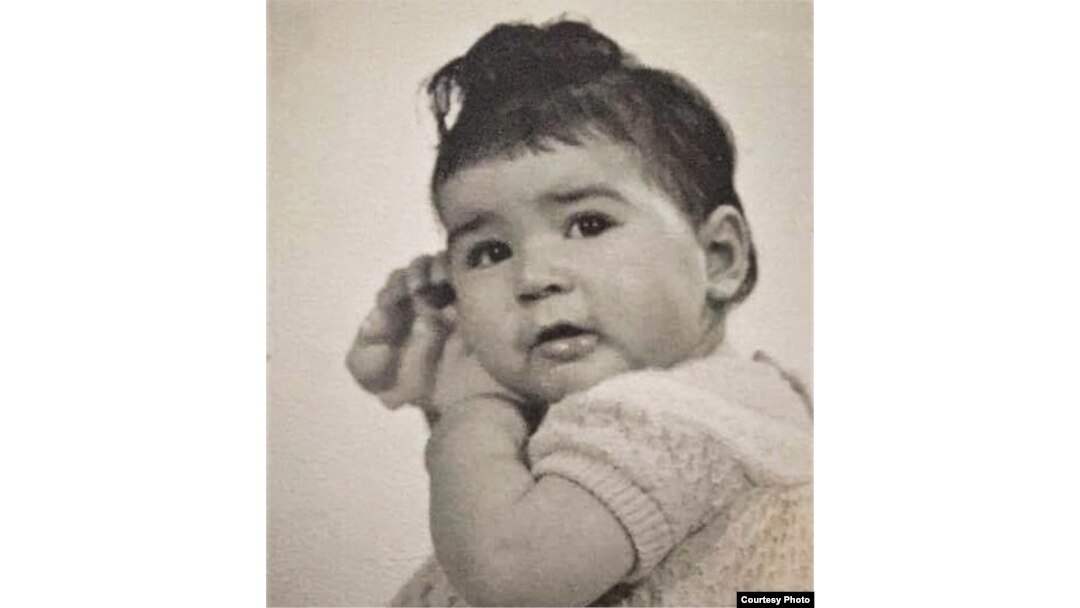

Henry Linwood Jackson, Otoe-Missouria tribe member, ca. 1965.

When he finally returned home to Red Rock, he did not know he had left behind an infant daughter.

This week, his daughter Gudrun Drofen Emilsdottir, now 51, is visiting the United States for the first time to spend Thanksgiving with the sister she never knew existed.

Like a Christmas tree

Emilsdottir, adopted shortly after birth, was 28 before she tracked down her birth mother.

“My mother told me that my father was a very good man,” she said. “But he was 12 years older than her, and she didn’t see any future in the relationship. So, she decided not to tell him that she was pregnant.”

Guðrún Emilsdóttir, circa 1967

Her mother gave Emilsdottir her birth certificate, which named her father, Henry Linwood Jackson.

“My nephew started looking for him,” she said.

Eventually, he contacted Native American genealogist Karen Vigneault, a member of the Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel in California who was profiled in an earlier VOA story. On Vigneault’s advice, Emilsdottir took a DNA blood test; they uploaded the results onto an online database and waited.

“My family tree began to light up like a Christmas tree!” Emilsdottir said. “And that’s when I found that I had a living sister, Kimberly Linebarger.”

This week, Emilsdottir flew to the United States to meet her sister - and visit her father’s tribe.

“It’s been like we knew each other forever. It’s peaceful. It’s good,” said Emilsdottir.

Tribal territory of Pawnee, Ponca, Omaha, Otoe, Kansa peoples (labeled in green) and contemporary Indian Reservations (labeled in orange). Background map courtesy of Demis, www.demis.nl.

Native roots

In the 1500s, the Otoe tribe migrated to the Missouri River valley, where, a century later, European traders would infect them with smallpox. Their numbers decimated and power diminished, the Otoe merged with the Missouria tribe.

The Otoe-Missouria was the first tribe to hold council with explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in 1804, a meeting that marked the beginning of U.S. sovereignty over American tribes.

Photo of a delegation of Otoe tribe members wearing traditional claw necklaces and fur hats, during an official visit to Washington, D.C., in 1881.

In the late 1800s, the U.S. government forced the Otoe-Missouria tribe onto a reservation on former Cherokee land in Oklahoma. It was there that in 1892, Henry Linwood Jackson’s father, Henry Sr., was born.

Piecing together the puzzle, Linebarger said she always believed she was an only child, so getting that phone call in August from genealogist Vigneault came as a bit of a shock.

“Karen asked if I’d be willing to talk to Gudrun, and I said, ‘Sure,'” she said, laughing. “And that’s how it started.” Linebarger has little memory of her father, from whom she was separated as a toddler.

“I’ve always known I was Native American,” she said. “I’ve known about my father all my life, but only bits and pieces of what people told me.”

At 18, Linebarger spoke with her father by phone for the first time.

“That’s when he gave me his tribal roll number,” she said. The two never met. He died in 2006.

Gudrun Drofn Emilsdattir, right, sister Kimberly Lineberger, center, and newly-discovered cousin Shelby Foster visiting the Oklahoma cemetery where their ancestors are buried.

Most Native American tribes require citizens to be able to prove lineal descent from someone named on historic government Indian rolls. Being able to provide that roll number and their birth certificates meant the sisters were eligible to become tribal citizens. Tuesday, they filled out membership applications at the tribe’s enrollment office.

“They will work on it in December, and in January they will contact me,” said Emilsdottir, who says she is optimistic their applications will be approved. That evening, the sisters flew south to Tucson, Arizona, where Linebarger will host a Thanksgiving feast, and Emilsdottir will meet yet more family members.

Guðrún Emilsdóttir, Reykjavik, Iceland, July 14, 2018.

“I’m cooking,” said Linebarger, listing the dishes: Turkey, stuffing, green beans, coleslaw, collard greens, biscuits and sweet potato pie. “I’m so thankful that I was around to do this with Gudrun. I would never have done this without her.”

Emilsdottir will shortly return to Iceland but is planning to return to Oklahoma in July 2019 for the “Encampment,” a pow wow the Otoe-Missouria tribe has held annually for more than 130 years. It’s an occasion for the tribe to sing, drum, dance and remember their history and traditions. And celebrate family, lost and found.