Medical clinics in Singapore are carrying out female genital cutting on babies, according to people with first-hand knowledge, despite growing global condemnation of the practice, which world leaders have pledged to eradicate.

The ancient ritual, more commonly associated with rural communities in a swath of African countries, is observed by most Muslim Malays in Singapore where it is legal but largely hidden, said Filzah Sumartono of women’s rights group AWARE.

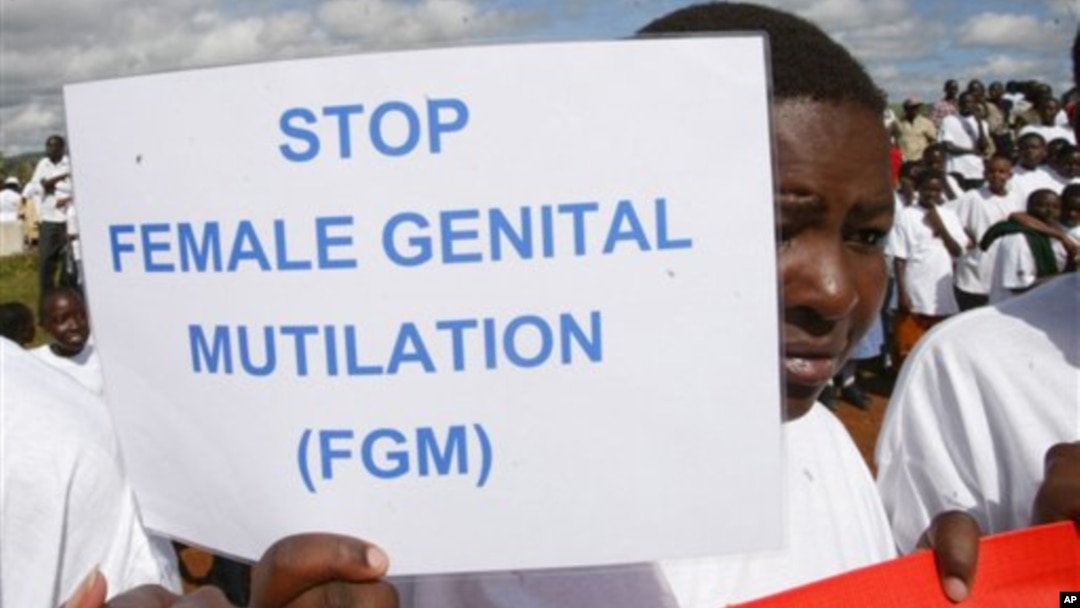

Worldwide, more than 200 million girls and women are believed to have undergone female genital cutting or mutilation (FGM), according to United Nations figures.

But its existence in Singapore, a wealthy island state that prides itself on being a modern, cosmopolitan city with high levels of education, shows the challenge of tackling a practice rooted in culture, tradition and a desire to belong.

Singapore's skyline gliters with lights as spheres in the waters of Marina Bay form the number '50' to mark Singapore’s 50th anniversary in 2015. AFP PHOTO / MOHD FYROL

Sumartono said it was too early to press for a ban in Singapore although many countries have outlawed the practice. She said they first needed to create more awareness and debate around the practice and galvanize public support for ending it.

“In my own circle of friends who are Malay and Muslim, 100 percent have been cut,” said Sumartono, who was cut herself at 1 month old.

“Whenever I bring up the subject with non-Malay they’re shocked and can’t believe it happens in Singapore,” she said.

The health ministry did not comment despite several requests.

Sumartono said FGM, known locally as sunat perempuan, was usually done before the age of 2 and may involve cutting the tip of the clitoris or making a small nick.

“Even within the community we don’t discuss this much,” she told Reuters by phone from Singapore.

“If a male baby gets circumcised there is this big celebration and prayer ritual, but if it is a female baby it’s quite quiet. It’s usually only the mother or grandmother making the decision. Sometimes the father doesn’t even know.”

She said cutting was usually done by medical professionals.

“We know five or six clinics offer the procedure, at around 20-35 Singapore dollars ($15-$26),” she added. “There's no legislation. It’s done openly. You can just call up to make an appointment.”

FILE - А traditional surgeon is seen holding razor blades used to carry out female circumcision, also known as female genital mutilation.

Religion and culture

The genital mutilation takes many forms and in some communities in Africa all the external genitalia are removed and the opening sewn closed.

Sumartono said although the type practiced in Singapore was milder, it was still a violation of a woman’s rights and underpinned the view that female sexuality must be controlled.

“What I get from talking to my community is, ‘Oh, it’s just a small cut so why are you complaining?’ But at its foundation,” she said, “it is really an act of violence against women. At infancy already, the child is taught that your body is not your own.”

Singapore, home to more than 525,000 Malays making up more than 13 percent of the population, is not included in the latest U.N. global report on FGM, and there are no studies on its prevalence. Although FGM is not mentioned in the Koran and predates Islam, some Muslims believe the prophet endorsed the ritual.

“Female circumcision, if done in the proper manner as prescribed by our Prophet Mohammad, ought to be continued,” one Malay woman from Singapore, who recently had her granddaughter cut, told Reuters.

The retired civil servant, who asked not to be named, said this improved hygiene and had no adverse affect on a woman’s sex life.

She said the amount removed was very tiny and should not be classed as FGM because it was different to the more extreme types of cutting, which can cause serious health problems.

The World Health Organization, however, says FGM includes any injury to the female genitals.

Global action

Sumartono said that even if women did not want to cut their daughters they often came under family pressure to do so.

“My mum didn’t want to do it, it was my grandmother who really pressured her. My grandmother said it’s our culture. Community pressure is really quite strong,” added Sumartono, who only started speaking out this year.

She said the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore had advocated the practice on its website, but this had been removed. The council did not respond to a request for clarification.

In 2012 the United Nations called for a global ban on FGM, increasing pressure on countries to take action. Last year world leaders agreed a target of eliminating FGM by 2030.

A U.N. report this year lists 30 countries where cutting is practiced, almost all in Africa. Indonesia is the only Asian country cited.

However, the Orchid Project, a charity that campaigns against FGM, says it believes cutting occurs in at least 45 countries and is more widespread in Asia and the Middle East than commonly perceived.

Research suggests sunat perempuan is common among Muslim Malays in Malaysia, which neighbors Singapore, and is also practiced in Brunei and part of southern Thailand.

“Often we think about it being a very rural practice linked to lack of education so it’s surprising when we find it in countries like Singapore and it shows there is still a lot more we have to understand about why this is being held in place,” said Orchid CEO Julia Lalla-Maharajh.