Alexander Khrgian quit Moscow for Montenegro in 2008 and immediately felt at home, setting up a law firm that helps the tiny country's outsized Russian diaspora do business, profiting from close ties between the two countries.

"We liked the climate, the people and conditions for doing business," said the lawyer. "So we stayed."

But a parliamentary election due on October 16 could test those ties. The vote, its outcome very much in the balance, could be Montenegro's last before joining the Western NATO alliance, an expansion dubbed "irresponsible" by Russia.

Attracted by the mountainous country's majestic coastline, 15,000 Russians flooded into the country after its 2006 split from Serbia, bringing money and Russian influence to the former Yugoslav republic of just 650,000 people.

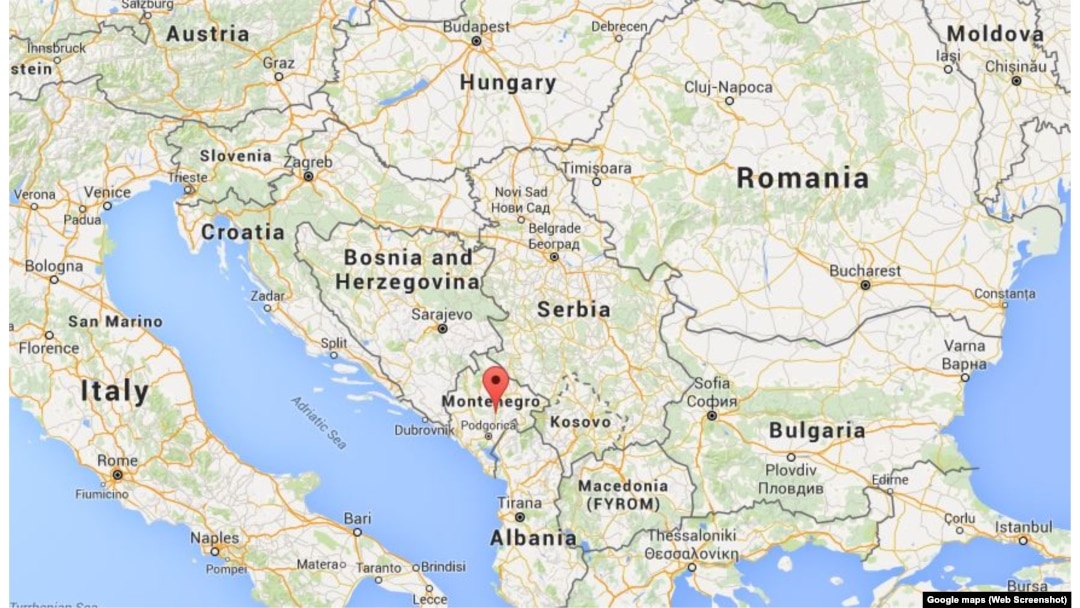

Montenegro

Western priority

Ushering Montenegro into NATO is a priority for the West, wary of Russian influence in a strategic region that is on the front lines of the migration crisis facing Europe.

"We want Montenegro in NATO because we are worried about Russian influence," said a Western diplomat in Serbia's capital, Belgrade, of a policy that divides the Adriatic country down the middle.

Montenegro was bombed by NATO 17 years ago when the alliance intervened to end Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic's campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. At the time, Montenegro was in union with Serbia.

Joining the alliance is the central pillar of Prime Minister Milo Djukanovic's campaign ahead of an election in which he is likely to face a tough challenge.

Djukanovic, who has been president or prime minister for more than 25 years, with one brief interruption, is accused by opponents of running the Adriatic country as a corrupt personal fiefdom, letting organized crime flourish.

He denies the allegations, but pollsters say NATO membership could act as a wedge issue, boosting support for eurosceptic parties and forcing his Democratic Party of Socialists to seek new coalition partners for the first time since 2006.

In one opposition advertisement, an actor playing the role of Djukanovic is shown having no answers, answering "NATO" every time he is challenged on alleged failings.

A man walks past election posters ahead of the parliamentary elections in Podgorica, Montenegro, Oct. 6, 2016.

Majority favors NATO

A poll by the Center for Democracy and Human Rights and the U.S. Embassy showed 50.5 percent would vote in favor of joining the alliance and 49.5 percent against if a referendum promised by the Democratic Front opposition party were held.

"Our main mission is to liberate Montenegro from Milo Djukanovic's rule," said Slaven Radunovic, a Democratic Front lawmaker. Djukanovic says opposition parties are Russian-funded, a claim they deny.

But Moscow, also concerned about suggestions of NATO expansion into Nordic countries such as Finland, is following events closely. An official from President Vladimir Putin's United Russia party recently urged the opposition to form a united front against Djukanovic.

The anti-NATO message has traction.

Montenegro's ties to its traditional Orthodox allies are too valuable for it to ignore. Tourism contributes 20 percent of economic output, and Russia and Serbia accounted for nearly 60 percent of visitors in 2016.

In a sign of strengthening ties between the three nations, volunteers last month set up a Balkan Cossack "army" in a ceremony rich in symbolism that was attended by Russian and Serbian bikers with Orthodox priests officiating.

Terrorism fears

Miladin Jokic, a 44-year old from the capital, Podgorica, said he opposed Djukanovic's party because NATO membership would expose the country to terrorist attacks.

FILE - A demonstrator holds a sign during an anti-NATO protest in Podgorica, Montenegro, Dec. 12, 2015.

"Montenegro has to stay away from it, especially at a time of such a big terrorist threat," he said.

The West, for its part, sees integrating the former Yugoslav republics into the EU and NATO as crucial for bringing stability to a region that suffered a decade of wars in the 1990s as Yugoslavia broke up into successor states.

Croatia and Slovenia, now in the EU, were the first to join NATO. Serbia and Montenegro are in talks over joining the EU, while Bosnia and Macedonia are yet to open talks. Montenegro received its invitation to join NATO in December.

In culture, history, religion and economics, links with Russia run deep. But for some, particularly the young, the West has more appeal.

"Geographically we are part of Europe, and we have to stand by those who are already in that alliance," said Ivan Bozovic, a 24-year old student.