Technology may be advancing rapidly in many fields, but many museums worldwide still do not have their collections of fossils easily searchable on-line. Specimens, called “dark data” are left in drawers, virtually hidden. There is an effort in the U.S. to bring this “dark data,” as it's called, into the light through digitizing museum collections.

Paleontologist Torrey Nyborg is helping with the digitization process by going through drawers filled with fossil crabs and making sure they are identified properly before the specimens are entered into a database at the National History Museum of Los Angeles County. In the process, he may have discovered a new species of crab.

“It’s a treasure hunt when you’re trying to find something new,” Nyborg said.

'Treasure hunt'

A treasure hunt is how some researchers describe finding specimens stored in many museums. Nyborg said there is no easy way to find a specific specimen hidden in the many drawers of museum collections.

“Right now it’s a crap shoot," he said. You don’t know. It’s a matter of just looking through the drawers and spending the time and doing the treasure hunt at this point in time."

With funding from the National Science Foundation, many museums are moving into the digital age, but it will not happen overnight said Austin Hendy of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

“I think there’s been a bit of a lag for the museum community to catch onto the availability of that technology but also to realize that there is a need for it,” Hendy said.

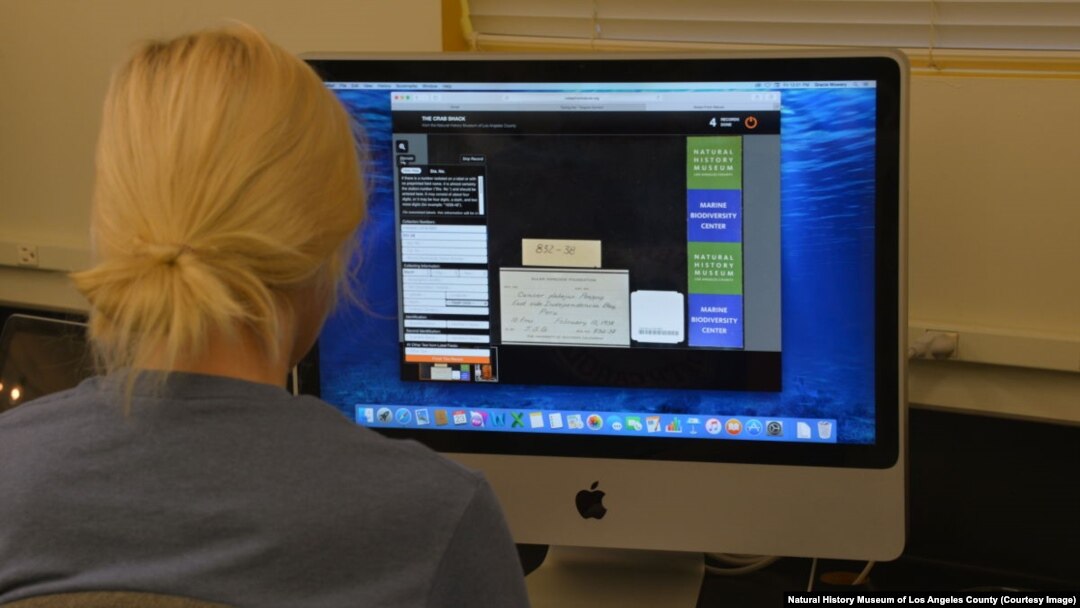

A crab specimin is digitized during a 'digitizing blitz' at the Marine Biodiversity Center of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

On-line data base

A grant from the National Science Foundation has allowed the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County to enter information and even photos of some of its specimens into a database so they can be easily searched on-line. Hendy said if museum collections across the U.S. and around the world can collaborate and add to the database, scientists will be able to get a critical mass of data for their research. He said it will help scientists see the bigger picture, such as how climate change in the past affected life forms.

“The data that we have in these collections allow us to actually see how whole communities have changed,” Hendy said, giving scientists clues of how life of Earth will respond to current changes in the climate.

Hendy said the ability to share specimens and data will change how scientists operate around the world.

“That has bound to increase research opportunities, foster collaborations across geographic, political and even language boundaries.” Hendy adds, “that’s one of the exciting aspects of what we’re doing with the digitizing process.”

Saving time and money

Carlos Jaramillo who is conducting research in Panama for the Smithsonian Institution said having specimens available on-line will also help save time and money.

”It really has transformed the way we do research because otherwise it would be very difficult to access most of the collections that there are worldwide,” Jaramillo said.

Integrated Digitized Biocollections or iDigBio is the central portal that digitally collects biodiversity data from museums. iDigBio’s Gil Nelson said there is a change in philosophy among scientists.

“I think the idea of open access data and data availability is becoming a little more common. There are still folks who would rather not share their data but I think those are becoming fewer and fewer and I think open access is becoming more and more the mode of operation these days,” Nelson said.

The trend of entering specimen records into a data is turning into an international effort. The U.S., China, Australia and European countries are sharing information on the best way of digitizing specimens so researchers from around the world can have access to specimens that span the globe.